On the first day of March this year, Scott Morrison declared his commitment to democratic principles. ‘My government will never be backward when it comes to standing up for Australia’s national interests and standing up for liberal democracy in today’s world,’ the prime minister told reporters. ‘We can’t be absent when it comes to standing up for those important principles.’ It was a deeply hypocritical statement from a leader who has overseen raids on journalists, the prosecution of whistleblowers, and the degradation of transparency mechanisms at the heart of our democracy. Standing up for important democratic principles is just about the opposite of what the Morrison government has done, domestically at least, in recent years. The secrecy-shrouded prosecution of Bernard Collaery makes that abundantly clear.

Much has already been written about the Collaery case, an insidious misuse of government resources that is contrary to the public interest and will only serve to silence whistleblowers. In this article, I want to look to the future. How does this end? And how do we prevent it from happening again?

First, though, a recap. Bernard Collaery is a Canberra lawyer. He is an elder statesman of the profession, having acted in many significant cases (including lawsuits arising from the Canberra Hospital explosion and the Thredbo landslide) and served briefly as ACT attorney-general and deputy chief minister. Collaery was also deeply involved in the independence movement of our neighbour Timor-Leste, acting as an adviser to the likes of Xanana Gusmão and José Ramos-Horta.

In 2018, Collaery was charged with five counts under the Intelligence Services Act 2001. It is alleged that Collaery breached a secrecy provision in that statute, through his communications with various ABC journalists. It was also alleged that he had conspired with his former client Witness K to contravene the secrecy provision. K, an ex-intelligence operative, had received approval from the Inspector-General for Intelligence and Security to seek legal advice from Collaery. It is alleged that Collaery and K conspired to pass information to the government of Timor-Leste.

And what information it is alleged to have been. The central issue underlying this entire prosecution is Australia’s alleged spying on Timor-Leste for commercial gain. Just a couple of years after Timor had gained independence from Indonesia, and had been left in impoverished ruins, Australia allegedly bugged Timor’s cabinet offices to gain the upper hand in oil and gas negotiations. It was a despicable act of espionage, morally bankrupt, aimed at enriching Australia and a few energy majors at the expense of a war-ravaged, newly born nation. Our neighbours, our friends – victims of the rapacious greed of our government.

Rather than prosecuting those who authorised this shocking intelligence operation, the government wants to shoot the messenger. Three years after being charged, Witness K pleaded guilty to a lesser charge; in June 2021, he was given a suspended sentence. But Collaery maintains his innocence. Since being charged, he has withstood a veritable procedural battering – over fifty court hearings and a dozen judgments over the extent of secrecy to be applied to his jury trial, and related issues.

The Morrison government, via Attorney-General Michaelia Cash, wants the trial to be mainly heard behind closed doors. One motivation for this secrecy is so that Collaery can be successfully prosecuted without the government having to publicly admit that it spied on Timor. It is not a crime to make something up, so Collaery will only be found guilty if the underlying matter, the espionage, is true. But the government has never admitted its wrongdoing, has never apologised, and it doesn’t want to start now.

This is not hyperbole. As much was stated, matter-of-factly, in a decision from Justice David Mossop of the ACT Supreme Court in 2020: ‘By this mechanism the Attorney‑General hopes to maintain a position of “neither confirm nor deny” (NCND) in relation to the subject matter of the [redacted].’ In other words, the Morrison government wants to tell a jury one thing, to convict a whistleblower, but refuses to admit the same thing to the Australian public.

Thankfully, the justice system disagreed. Despite Mossop’s initially granting the secrecy orders sought by Cash (the deck is stacked in the attorney-general’s favour, with the court required by law to give greatest weight to their views), on appeal Mossop’s colleagues upheld the importance of open justice and ordered a largely open trial. In a public summary of its judgment, released in October 2021, the ACT Court of Appeal indicated that a secret trial would pose ‘a very real risk of damage to public confidence in the administration of justice’. The summary added that ‘the open hearing of criminal trials was important because it deterred political prosecutions’.

It is at this point that the pre-trial proceedings took a turn that would be outlandish even in Franz Kafka’s The Trial. The attorney-general appealed to the High Court – not to challenge the underlying decision of the Court of Appeal, but to contest the Court’s refusal to redact parts of their written reasons. The government wants to keep a judgment that said no to secrecy itself secret. The case remains before the High Court, awaiting a decision on whether the attorney-general will be granted special leave to appeal (a hearing is expected in mid-April). If special leave is granted, the High Court will weigh in on the redactions later this year. If not, we might finally see a judgment, handed down six months ago, that said no to a secret trial. It is perversity heaped on perversity.

It does not end there. Notwithstanding its robust defence of open justice, the Court of Appeal sent the ultimate secrecy question back to Justice Mossop, because when it was first argued before him, the government wanted to put evidence that it said was so secret only the judge could see it. Contrary to foundational principles of procedural fairness, the attorney-general’s lawyers submitted that they would only provide the evidence if Collaery and his lawyers could not see it. Mossop decided that he did not need to see the evidence to make his decision – now that the Court of Appeal has decided against the attorney-general, the government is back for another bite of the cherry, this time with secret evidence in hand. In mid-March, Mossop agreed to receive and consider the secret evidence, shrugging off constitutional concerns that had been argued by Collaery’s barristers. Collaery will therefore have to relitigate the fight over whether his trial should be in secret, effectively blindfolded, unable to see the evidence on which the attorney-general is relying.

And so, almost four years after Collaery was charged, a trial remains beyond the horizon. The current parallel litigation might be concluded by the end of this year. Even that is uncertain, particularly if Mossop, having agreed to receive secret evidence, insists on a secret trial, which may then be appealed – to the Court of Appeal and even the High Court. More pre-trial fighting is likely; no aspect of this case has been uncontested. (In one judgment, in 2020, Mossop complained that the relevant issue, over parliamentary privilege, might have been resolved by consensus; instead, ‘the parties allowed it to become another front in their greater war’.) The punishment by process inflicted on Bernard Collaery by the government rolls on.

So how does it end? The Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (CDPP) or the attorney-general could drop this prosecution today. The Morrison government could apologise to Timor-Leste and Collaery, pardon Witness K, and commit to comprehensive law reform directed towards protecting whistleblowers and promoting transparency. That would be the preferable outcome, even if it is alarming that it has taken them four years to reach the obvious conclusion that there is no public interest in prosecuting whistleblowers.

The CDPP has the authority to drop a prosecution at any time prior to a trial. They should exercise that authority. The Prosecution Policy of the Commonwealth provides that the guiding question is at all times whether ‘the public interest requires a prosecution to be pursued’. Prosecuting whistleblowers is not in the public interest. It punishes courageous Australians who have spoken up and revealed wrongdoing.

No one really disputes that what Collaery is alleged to have said is true – that Australia spied on Timor-Leste. Prosecuting someone for telling the truth, when that truth reveals government wrongdoing, is profoundly undemocratic. Prosecuting whistleblowers also has a chilling effect on other Australians who might speak up. Discouraging people from calling out wrongdoing is antithetical to the public interest.

If the CDPP will not exercise their discretion to discontinue the prosecution, then the attorney-general must. At common law, the government has the prerogative power to discontinue the prosecution – in technical terms to direct a nolle prosequi (‘no bill’) in relation to a criminal charge. Section 71 of the Judiciary Act 1903 also provides express statutory authority for this power. The attorney-general can, at any time, end this madness.

Cash has so far refused to drop the case. At every Senate estimates hearing, upon being grilled about the Collaery case by the likes of Senator Rex Patrick, Cash offers the same excuse. In the most recent exchange, in February 2022, the attorney-general insisted that it was ‘not appropriate for me to intervene to discontinue this matter … it would be extraordinary and, given its nature, represent political intervention in a process that … conventionally, has been independent’.

This is wrong for two reasons. First, the nature of the charges against Collaery required the attorney-general’s consent for the CDPP to proceed. The brief reportedly lay dormant on former Attorney-General George Brandis’s desk, for good reason. It was not until Christian Porter became the nation’s first law officer that the case was given the green light. It has therefore been political from the start; there is nothing apolitical about refusing to intervene now. Second, this is an extraordinary case, and extraordinary cases deserve the exercise of extraordinary powers. Those powers exist for a reason.

Hopefully, the CDPP or the attorney-general acts. If they continue to refuse to drop the prosecution, it is incumbent on the next government – whether Coalition or Labor – to intervene. Labor has been making the right noises, thanks to agitation by Canberra MPs and senators. If Labor is elected, Mark Dreyfus, the current shadow attorney-general, who was responsible, back in 2013, for the enactment of federal public sector whistleblowing laws in the first place, will have the power to end the case. If he fails to do so, it would represent a great betrayal.

The alternatives are grim. Without the government or CDPP dropping the prosecution, the case will, eventually, go to trial. At the earliest, it would be heard by a jury, in open or closed court, in mid-2023. The following year is more likely. Whatever the outcome, an appeal seems inevitable – further prolonging the prosecution. It is not impossible that the case could still be on foot in 2028, a full decade after Collaery was charged (at which point he will be in his eighties). Even a not-guilty verdict would be a pyrrhic victory, in a case that should never have commenced. The alternative, that Collaery is found guilty and imprisoned, for allegedly speaking up about Australia’s wrongdoing against Timor-Leste, is intolerable.

Collaery is not the only whistleblower currently on trial. David McBride spoke up about alleged war crimes in Afghanistan, while serving as a defence force lawyer. Richard Boyle, while working at the Australian Taxation Office, blew the whistle on unethical debt recovery practices. Both thought they were doing the right thing – speaking up internally, and then to an oversight body, and only going public, to the ABC, as a last resort, as is expressly permitted by whistleblowing law. Both have been vindicated: the Brereton Report alleged horrendous conduct by Australian forces in Afghanistan; an investigation by the Senate confirmed Boyle’s allegation. And yet both are on trial, later this year.

How can we ensure that these types of cases never happen again? Whistleblower protection reform is essential and long overdue. An independent review told the federal government to improve the Public Interest Disclosure Act, which protects public servant whistleblowers, in 2016. Despite promising to do so, six years later the law remains unchanged. Whistleblowers are suffering as a result. Whoever wins government should prioritise whistleblowing reform as part of a wider suite of integrity measures, including a federal anti-corruption commission.

The three prosecutions underscore the failure of existing whistleblower protections. The PID Act provides no avenue for external disclosure by an intelligence officer, no matter how egregious the wrongdoing. McBride and Boyle, meanwhile, both thought they were abiding by the law – only to find themselves on trial. Each is defending the case on the basis of the PID Act; hopefully they succeed. But the very fact of the prosecutions shows that the protections for whistleblowing to the media are too narrow and technical. Reforming prosecutorial guidelines, to underscore the lack of public interest in prosecuting whistleblowers, is important. A general public interest defence to secrecy offences, as exists in other jurisdictions, would provide an additional safeguard.

Finally, we can prevent future prosecution of whistleblowers, and more raids on journalists, by making it clear that this is unacceptable. By attending rallies – the Alliance Against Political Prosecutions convenes outside the Supreme Court in Canberra at almost every Collaery court date. By contacting our elected representatives and expressing our displeasure at these prosecutions. And by doing all we can, as individuals, to support and empower those around us to speak up about wrongdoing, of whatever nature. Collaery, McBride, and Boyle might be the faces of whistleblowing in our popular imagination, but each week there would be thousands of people across Austra-lia who speak up about wrongdoing at work. Some are protected and empowered, too many others are punished. Research shows that eight in ten Australian whistleblowers suffer some form of backlash. Changing that culture is the ultimate challenge.

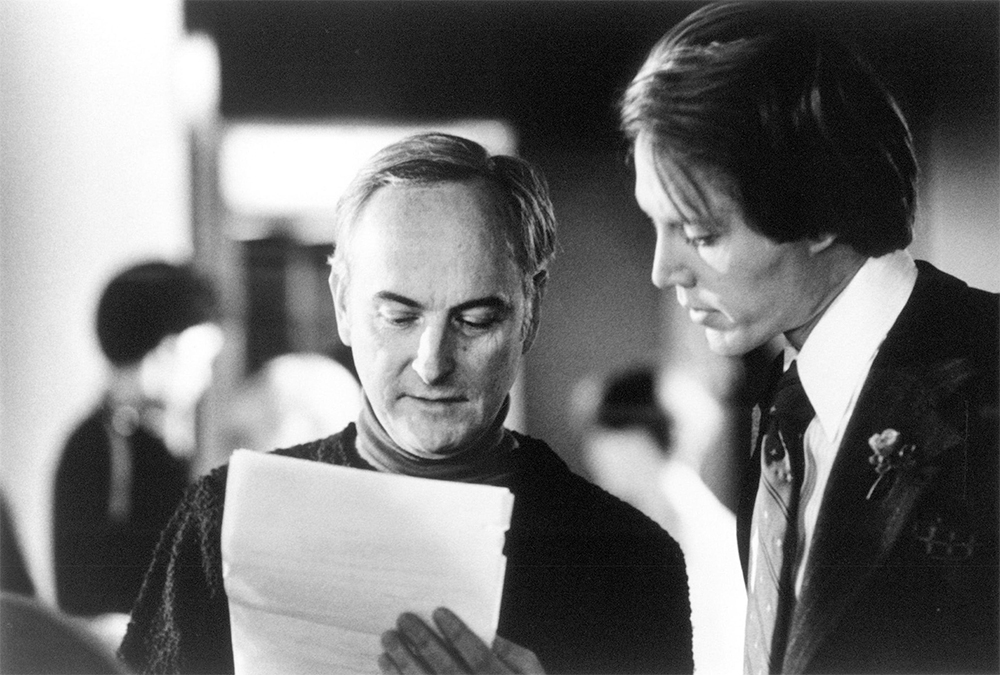

I try to attend every court date in the prosecution of Bernard Collaery. I feel it is the least I can do, to show solidarity and keep the public informed about this unjust case. Sometimes I am expelled from the courtroom after a few minutes, together with the handful of journalists who keep an eye on the proceedings, when the court goes into closed session. Other times I watch from the back of the courtroom as the attorney-general’s barristers – eminent members of the Sydney bar – make their submissions, before Collaery’s counsel, all acting for free, in the public interest, have their turn.

What I find most infuriating, and why the prime minister’s recent homily about defending democracy drew my ire, is how the law is used to wrap this prosecution in respectability. Smartly dressed silks orate as if this were any other case – the application of the law to the facts, nothing out of the ordinary. An uninformed spectator, on stumbling into courtroom six at the ACT courts building, could easily conclude that there was nothing to see here, just the wheels of justice in motion.

They would be wrong. There is no public interest in prosecuting whistleblowers. Doing so in secret is the sort of thing more commonly associated with authoritarian regimes than with liberal democracies. Whistleblowers should be protected, not punished, and certainly not prosecuted behind closed doors for speaking up about abhorrent government wrongdoing. The Collaery prosecution is a stain on our democracy, an insult to our legal system.

Scott Morrison: if you really care about democracy, drop this case now and fix our broken whistleblower protection laws.

This is one of series of politics columns generously supported by the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas.

_(retouched)%20copy.jpg)