- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

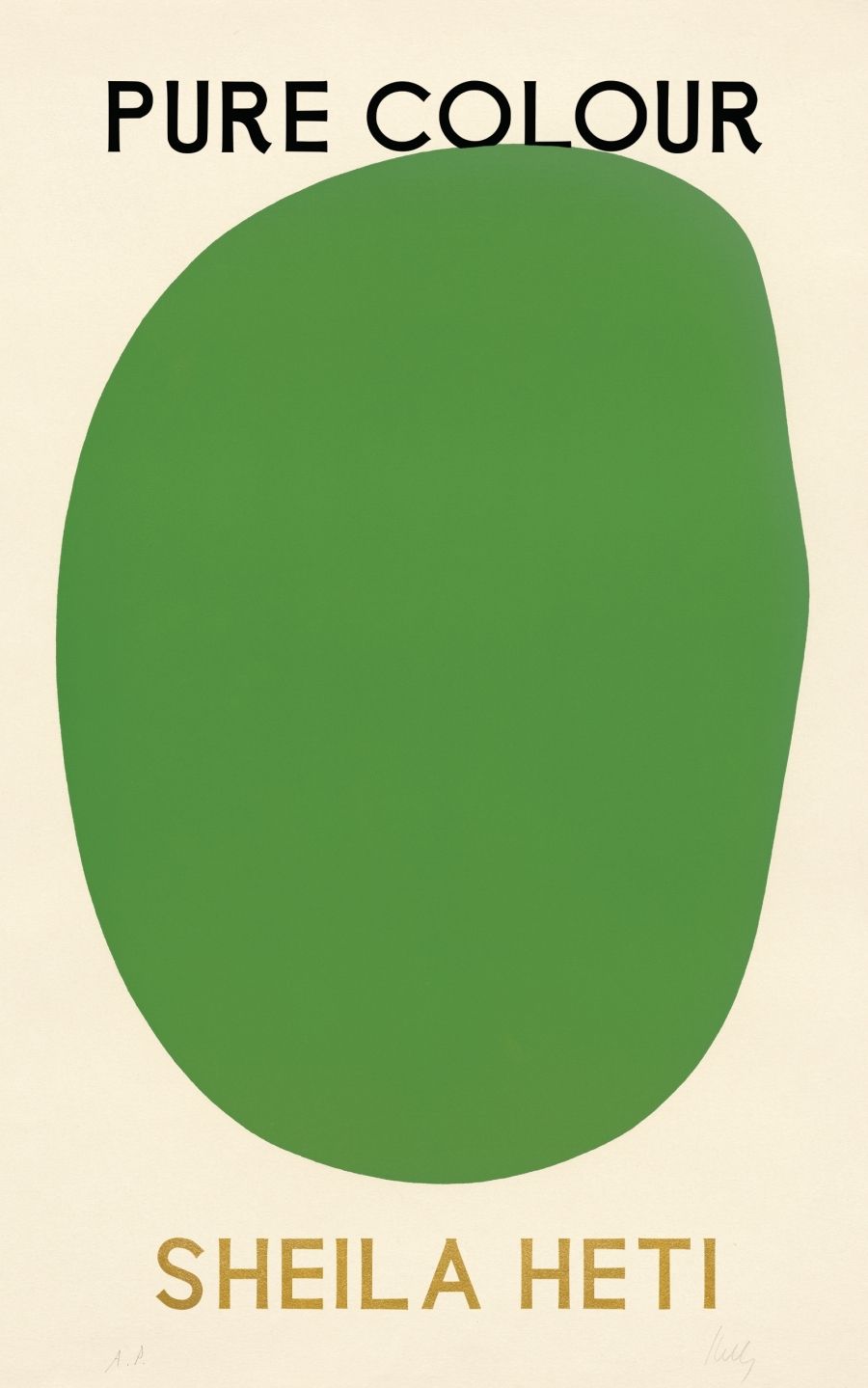

- Article Title: God's first draft

- Article Subtitle: Art and the anthropocene in Sheila Heti's novel

- Online Only: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Sheila Heti’s fifth novel Pure Colour imagines God as an artist who has just stepped back from His first draft of the universe. The ensuing story takes place in the expansive moment in which He decides whether or not to scrap it all and start again. The stakes of the narrative could not be higher – if it were not for the marked absence of any sense of human agency.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Pure Colour

- Book 1 Biblio: Harvill Secker, $32.99 pb, 224 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/doqqLq

Heti’s God created humans so that they could critique His first draft from the inside. The narrator describes members of our species as being descended from three archetypal art critics: first, the bird, concerned only with the aesthetics of life; second, the fish, who deplores individualism and worries themself with the good of the greater community; and third, the bear, who values close bonds with ‘those they can smell and touch’. The lore feels strange and inconsistent throughout the novel but these qualities work well to convey a sense of being told an impromptu bedtime story by a loving but world-weary parent.

Heti goes on to weave a strange kind of fable, one that offers both a finely embroidered individual life as well as a slapdash tapestry of the Anthropocene at large. These pictures, while thought-provoking, feel less authentic than the window Pure Colour provides into a contemporary writer’s existential crisis – a writer living on the precipice of unprecedented ecological grief. Heti’s crisis grows more explicit when the narrator remarks upon the continued relevance of books that are many centuries old, but notes that ‘none of the books which were twenty years old were the least bit relevant anymore’.

Pure Colour questions not only its own relevance in the face of human extinction, but the future relevance of the entire cultural archive: ‘it’s clear to me now that art is made for our situation. Whatever comes will be another situation, and our art won’t be needed for it.’ Heti’s logic cannot be faulted, but it is this sense of indifference in the face of annihilation that renders the text so unsettling. Heti allows the threat of climate change to loom over the reader while her characters go about their lives largely unfazed – after all, what are they, mere critics, supposed to do? As the audience, we too become critics and the book uses this positionality to plays tricks on us in regard to our agency. On one hand, the omniscient narrator assures us that responsibility for Earth’s destruction lies solely in God’s artistic temperament, while on the other, the novel’s evocation of the fabular would suggest there are real-world lessons for us to learn.

Pure Colour’s overall tone is aloof but there are still moments of intimate characterisation in which to invest. These are often delivered through well-observed conflicts that occur between the differing tribes of art critics. For example, our bird-like protagonist, Mira, grapples with the genuine love she feels for her bear-like father, while accepting that her love can never match the all-consuming nature of his own. These poignant human depictions are often relegated to the text’s background in favour of the conceptual and the thematic. This tendency makes the novel feel, at times, like an exercise in aphorism. Heti’s observations are insightful, but they would be easier to savour if they, and the reader, were given more space to breathe.

Despite its unusual lack of sentimentality, Pure Colour is fascinated with various forms of human grief: the loss of human culture through ecological collapse; of community through the ageing process; and of loved ones through illness. The emotions Mira experiences after her father’s death are complex and relentlessly sexualised, as when the narrator describes ‘the peace after an orgasm was nothing compared to the peace that fell over her after his death’ or that Mira ‘had felt his spirit ejaculate into her, like it was the entire universe coming into her body, then spreading all the way through her, the way cum feels spreading inside’. This figurative perversion of death and daughterhood feels like a continuation of Heti’s critique against our obsession with reproductive pasts and futures.

Sheila Heti (photograph by Sylvia Plachy via Penguin Random House)

Sheila Heti (photograph by Sylvia Plachy via Penguin Random House)

The organic and seasonal qualities of grief are beautifully captured in the novel’s strange ascent into surrealism. Mira, impregnated by her dead father’s soul, is finally at one with him, but their combined existence is now confined within a single leaf. Throughout Pure Colour, humans are portrayed more as observers than active participants, and Mira’s interlude in the leaf pushes this portrayal to its extreme. The device brings the novel’s action to a grinding halt and further limits the already scarce opportunities for readerly participation. The effect is akin to that of an emotional anaesthetic which, though frustrating, may help transmit Mira’s own affective state to the reader.

Those familiar with Heti’s oeuvre will pick up on curious recurrences throughout Pure Colour. In How Should a Person Be (2013), Heti’s eponymous narrator–protagonist expressed unusual affection for Manet’s Asparagus: ‘It was the most moving thing I had ever seen, painted so tenderly and with such a loose hand.’ Pure Colour dedicates three of its own pages to the same painting, but this time it is the fictional protagonist Mira who is deeply stirred. In Motherhood (2018), Heti used the autofictional form to explore her own scepticism around the unchecked urge to procreate, whereas in Pure Colour, the omniscient narrator speculates: ‘how strange and sad our world will seem to them … that we once had to create people with our own bodies.’ Pure Colour’s God may have just completed His first draft of existence, but the return and revision of ideas previously attributed to Heti’s autofictional alter-egos may leave readers wondering: what draft of Her authorial universe are we critiquing now?

Comments powered by CComment