- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Virtuosity

- Article Subtitle: New poetry by Anthony Lawrence and Subhash Jaireth

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Australia has a stylish new poetry press. The two books reviewed here by Life Before Man, the poetry wing of Gazebo Books, preference book cover art and poem above all the usual paraphernalia: publishing details, barcodes, author notes – even the epigraph – are tucked into a back page, and there are no apparently distracting contents pages or page numbers. Most of the poems sit neatly on the right side of the page with a private blank beige page buffer. There’s orientation in a contents list, and I trust the poets have a choice about whether they want one. That said, there’s a holiday-like liberation in slipping through unmoored. It’s a subtle reading experience, but do these aesthetic somewhat precious innovations justify the use of extra paper?

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Luke Beesley reviews 'Ken' by Anthony Lawrence and 'Aflame' by Subhash Jaireth

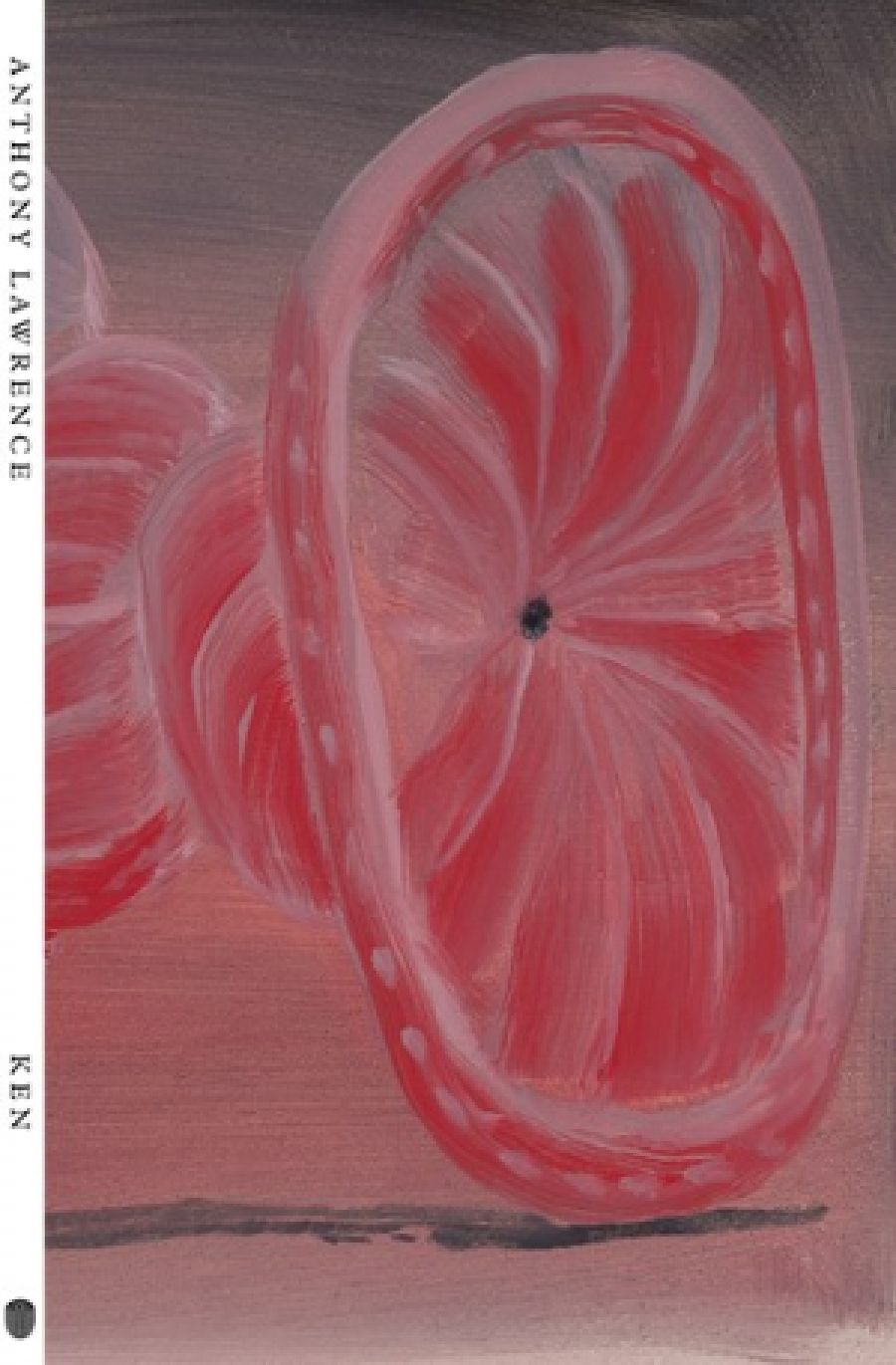

- Book 1 Title: Ken

- Book 1 Biblio: Life Before Man, $19.99 pb, 154 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/mgbGAZ

- Book 2 Title: Aflame

- Book 2 Biblio: Life Before Man, $19.99 pb, 134 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2022/Mar_2022/Aflame.jpg

- Book 2 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/Ke9z1z

The protagonist of Anthony Lawrence’s seventeenth collection, Ken, is the titular plastic boyfriend of the Mattel Barbie doll. It’s no coincidence that the Ken doll was first produced in the late 1950s, when Lawrence was born – a mode of self-reflection in the context of hypermasculinity is not unusual in an Anthony Lawrence poem. Replace ‘Policeman’ with ‘Ken’ in ‘A Policeman Revealing Extremes of Emotion’ at the end of his Skinned by Light (2002) and you have a typical title here. Though the poems of Ken are more about playful language and aesthetic extracurricular landscapes as Ken ‘waits for playtime to save or kill him’ (‘Ken Considers’).

A montage – to capture this book-length, twenty-seven-poem focus on Ken’s hijinks – seems apt. We observe ‘Ken the builder lawyer beach comber / doctor drain cleaner teacher lover / homewrecker counsellor vet’, via suburban rooms and obscure tortures. He is finger-printed, buried in sand, ‘smeared with honey for the ants’; he deep-sea dives, gets his shiny enlightened forehead anointed with star anise in Rajasthan (‘Spiritual Ken’), and finally farewells Barbie in a poem called ‘Pandemonium’: they ‘embraced like ampersands // in a sentence about disease’. The mise en scène is more John Cassavetes than Home and Away. Ken, bewildered hobbyist, slides through decades beyond nostalgia for The Rolling Stones towards climate activism and the mask accessory necessity of Covid-19. Several poems coalesce into a taut climax, such as this delectable musical endline: ‘Barbie, he said / Ken he said, with her intonation’.

Every stanza resembles the two below – three lines (one indented, then two), no commas or full stops. Lawrence uses the stanzas and the space between them to manipulate pace; he sets up expectations and trips us up. Cleverly, the form reflects the limited arc of Ken’s plastic parts and Ken’s (and poetry’s) agility in spite of this. Here is poetry making a dream of these three-line restrictions. In the dream, Ken’s ‘father’ pinches his bicep or ‘gun’:

as he liked to say he said

you are getting strong son you are

a fine young fine youngKen woke still waiting for his father

to complete the sentence

fine young what dad he asked then

The concept of staging is ever-present. There is much here implied about what’s outside Ken’s action, how he’s choreographed. In one scene, this direction arrives beautifully in the shape of the wind, which ‘comes in & spins him full circle’. It’s not always clear if the puppeteer, so to speak, is adult (‘some / collector’) or child. One scene ‘trembles & dies away with an outtake / from Thunderbirds’. In another cinematic moment, Ken is positioned ‘under a lamp like the sun / at midday in the Lion King’, and suddenly the lamplight is butterscotch-cartoonish.

There are innumerable moments of lyrical virtuosity in this commitment to the Ken doll, yet in the long run of Lawrence’s oeuvre the book may turn out to be more curiosity than masterpiece – a gem of a B-side.

Aflame is the fifth poetry collection from Indian-born, Canberra-based poet, novelist, essayist and translator Subhash Jaireth, who also spent nine years in Russia. Indeed ‘Moscow – 1974: Oratorio in Two Voices’ is the first of Aflame’s three parts. These ‘Voices’, though, are more elusive; its song comes over like the broad strokes of allegory. The language of Aflame is often simple, sometimes familiar. The night is ‘raven black’, the moon is ‘veiled by cold mist’, a thought ‘flashes’, the sea is ‘turquoise’, a face is ‘ashen white’ – all this within the first few pages. But Jaireth’s images are imaginative, and he has an intricate control over the poem’s spaces and rhythms (know that the beat in ‘veiled by cold mist’ enhances the poem).

In this introductory twenty-piece prose-poem sequence, a woman and her lover meander dreamlike in Moscow through concerts and galleries and markets. There is a game of eggs with a nun; a man with a painted face sings to a horse in a stage play. The poems contain mishearings, echoes, doublings and strange musical puzzles: ‘The blood on the wedge could be his or of the pigeon’s.’

There is intensity and an atmosphere of novelty evoking Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities or the surprise and strangeness of Michal Ajvaz. Indeed a few pages over we find: ‘Like Calvino’s Marco Polo he wants to trace invisible parabolas the swallows cut in the air. Without them the skies are hollow, he says.’

Aflame’s second part, ‘In Praise of Silence’, consists of twenty-one prose poems – almost microfictions – each swivelling off wry haiku from Japanese poets including Matsuo Bashō and Kobayashi Issa.

In a piece following ‘Kobayashi’s snail’, the protagonist walks up a mountain, but the reader is wonderfully lost in the stickiness of the poem’s circling discourse. Uniquely, Jaireth brings native Australian animals to the quietude of Japanese minimalism.

Jaireth looks to mirror the dysphoric whimsy of these haiku masters, but in Japanese filmmaker Isao Takahata we have an example of a counterbalance that feels more dynamic. In his delectable My Neighbours the Yamadas (1999), Takahata wittily contrasts the crass and pitiful Yamada family with epigraphic haiku by Bashō.

Aflame’s third part is the titular sequence dedicated to Tibetan Buddhist monks. Over fifty pages, in twenty-seven shortish poems, mostly quatrains, the feel is a melodic, loose villanelle, a lost walk, a long night, as the poem returns to its central horrible nightmare about a mother and her goat, both shot by a soldier. There’s contemplation in the repetition and transparent simplicity, and the poem builds to catharsis with bloodstained milk:

in the bowl she held

when the bullet the bullet hit herthe bowl breaks it breaks

into pieces I gather

in my dream to hold the bowl,

from which I drink and drink

The significance of each player – mother, bullet, bowl – deepens as they’re interleaved. To follow just one strand, a carved finch sits in a nest or pecks at grains and twitters ‘enchanted syllables’. Later it receives a mother’s whisper or becomes a measure word – not a sliver or a twist but a ‘finch of compassion // for the soldier’. Eventually, the wooden bird enters the throng via a tourist market.

The poems of Aflame often return to the act of writing. After the dream’s trauma – also hinted in Jaireth’s continually strung-together phrasing – the protagonist sleeps (presumably again) clearly, empty: ‘the cleanest sliver [or finch?] of an oak bark / akin to the one on which my mother / taught me to scribble words I remember’.

Comments powered by CComment