- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The snares of grief

- Article Subtitle: Pathways, not closure

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

We all seem to be thinking about grief lately. As Covid keeps many of us away from loved ones and people who are dying or have just expired, how we process death has received a renewed focus. The number of memoirs and guides and stories about grief and loss that have been published in the past two years – over two hundred – is staggering. It is a challenge to write about grief. Every society on earth has its own forms and rituals around grieving, its own texts on what grieving is like. Trying to find something new or original to say is daunting. What we are left with are our own words, our own terrible experiences to put down upon the page.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

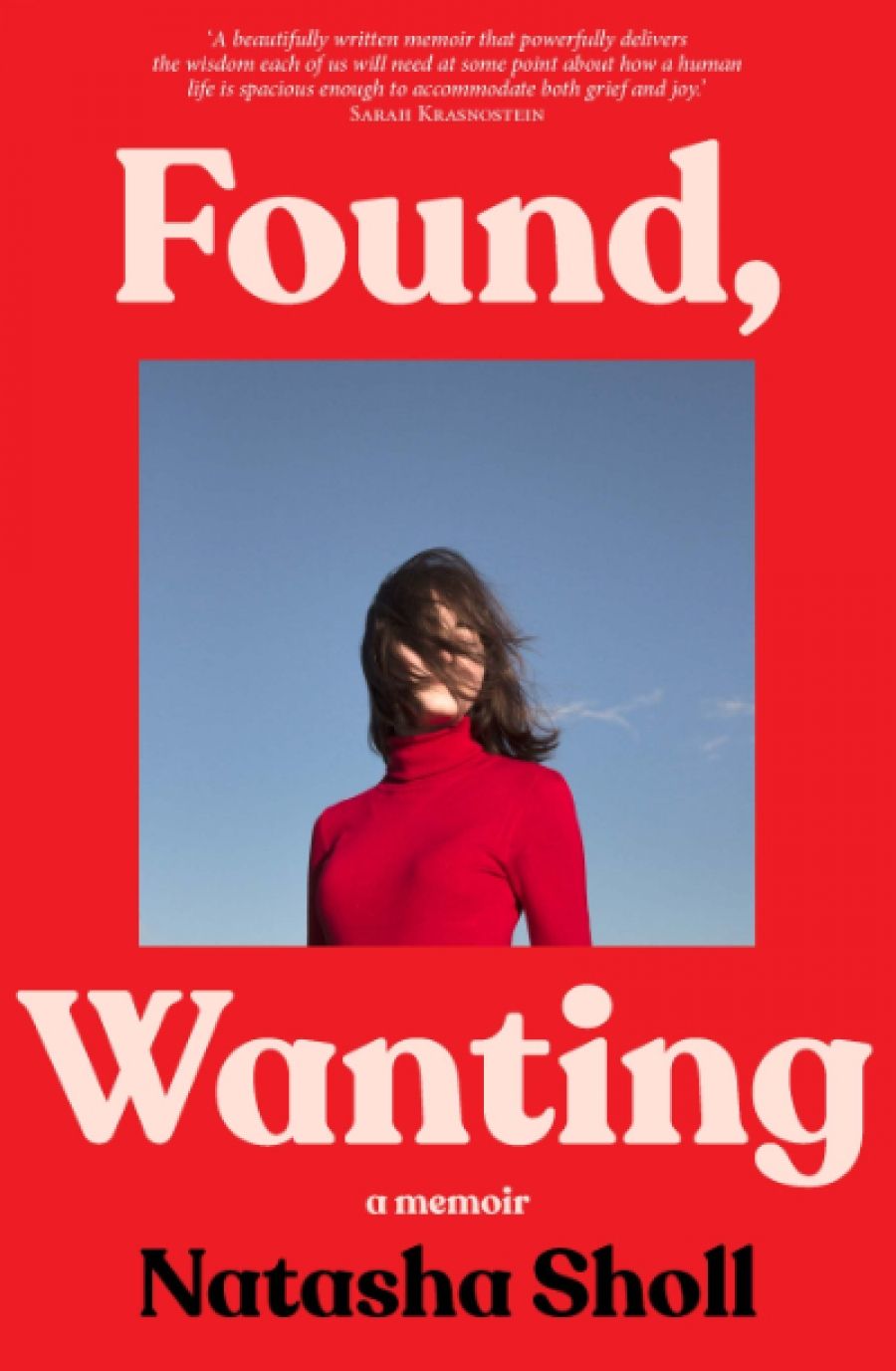

- Article Hero Image Caption: Natasha Sholl (photograph via the author's website)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Natasha Sholl (photograph via the author's website)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Andrew Broertjes reviews 'Found, Wanting: A memoir' by Natasha Sholl

- Book 1 Title: Found, Wanting

- Book 1 Subtitle: A memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Ultimo Press, $32.99 hb, 279 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/4eBoy1

When she was twenty-two, Natasha Sholl lost her partner, Rob, from what seemed to be Sudden Adult Death Syndrome. Nine years later, she would lose her brother Matt. How she slowly regained her life during those years, and pulled herself out of the darkness, is narrated in the fractured and haunting memoir Found, Wanting. Sholl, a Melbourne-based writer, has presented an open and uncomfortably honest account of her life during those years. She takes us through the initial shock of grief, the depression, the breakdown and the eating disorder that developed as a result of that grief, and finding someone new, trying to move on from death in a way she realises ultimately is not possible. All Sholl can do is build a life different from the one she thought she would have. As she recalls this process, touchstones familiar to anyone who has suffered loss appear: relatives and friends bringing endless food, the halting attempts to respond to comments like ‘I have no words’, the aspects of grief that Sholl, like all of us, feels compelled to perform when we just want the world to go away:

From the outset it was clear I was being watched. People hovered. Waiting. And so I had no choice but to act out what I thought grieving looked like. That I would have no appetite was a given. People turned up on my doorstep with home-made pumpkin soup, chicken soup, vegetable and barley soup. Broths and liquids. At mealtimes I smiled and shook my head politely and they nodded sympathetically. I mean, what kind of girlfriend would eat a steak after they just let their boyfriend die?

It is a performance: a performance that is exhausting.

Mourning is a complicated, messy process. After my first major loss, a close friend wrote to me and said, ‘There is no right way or wrong way to grieve, and I’ll remind you of that from time to time over the coming weeks and months. We, your friends, do not expect you to do anything, be anything, or move on to anything along any timeline, or in any order.’ Nearly two years to the day after sending that email, he would be dead himself. I had no religion, no particular cultural framework to draw upon when dealing with my losses. The frameworks of culture and religion are important. For Sholl, who describes herself as a lapsed Jew, the rituals and rites of the Judaic faith provided pathways, but not closure. And some of those pathways would be blocked:

Rob’s parents’ house became the central hub. Part of this was instinct, a search for comfort. To be together. Part was tradition. Rob’s family was sitting shiva, the week-long mourning period in Judaism for first-degree relatives. I was not technically part of this process because we were not married. Another reminder of what I had lost: the future.

At times, Sholl’s writing can be frustrating. The chopped sentence fragments, particularly in the first half of the book, convey a sense of unease. The reader is not allowed to settle. There are interludes between the main chapters, lengthier fragments and thoughts that mirror the scattered sentence structure that coils throughout the book. It can be unsettling, uncomfortable, but perhaps that is largely the point. Sholl was splintered, fractured, struggling like so many of us who have experienced loss to put herself back together and function on a day-to-day level.

Found, Wanting is not an easy read for anyone who has been through the grieving process. At times I found myself wondering how anyone could have had an experience so different from mine. She’s misremembered, I thought. Too much time has passed. And then there were moments that forced me to put the book down and go for a walk to clear my head, to clear the grief that came rushing out in front of me. Sholl writes about helping her brother’s wife, Fiona, put out Matt’s clothes for charity, and I realise that my partner’s clothes are still all packed up, more than five years later, still going nowhere. Sholl recounts the moving-on process of her other brother, Andrew (oh, the synchronicity!), who began to get fit and compete in marathons for charity. In 2019, three years before I read this book and two years after the death of my partner, I decided to do a half-marathon for charity. When Sholl writes that ‘grief itself is an endurance sport’, I know exactly what she means. In her memoir The Year of Magical Thinking, Joan Didion wrote of the need to ‘go to the literature’ when grappling with loss. With Found, Wanting, Natasha Sholl has added an important work to that canon, a wrenching step for those in the midst of their own ‘endurance sport’, and a necessary read for anyone supporting someone caught up in the snares of grief.

Comments powered by CComment