- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: In essence, freedom

- Article Subtitle: Growing up between socialism and liberalism

- Online Only: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Freedom’ is a word that slips off the tongue easily. As the moral philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre notes in his essay ‘Freedom and Revolution’: ‘No word has been more cheapened by misuse. No word has experienced more of the tortuous redefinitions of politicians.’ In the essay, MacIntyre turns to Karl Marx to recover the idea that human beings are essentially free. With the same source of inspiration, but through a poignant and often funny memoir of coming to age in state-socialist Albania, Lea Ypi’s Free attempts the same task.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Michael Lazarus reviews ‘Free: Coming of age at the end of history’ by Lea Ypi

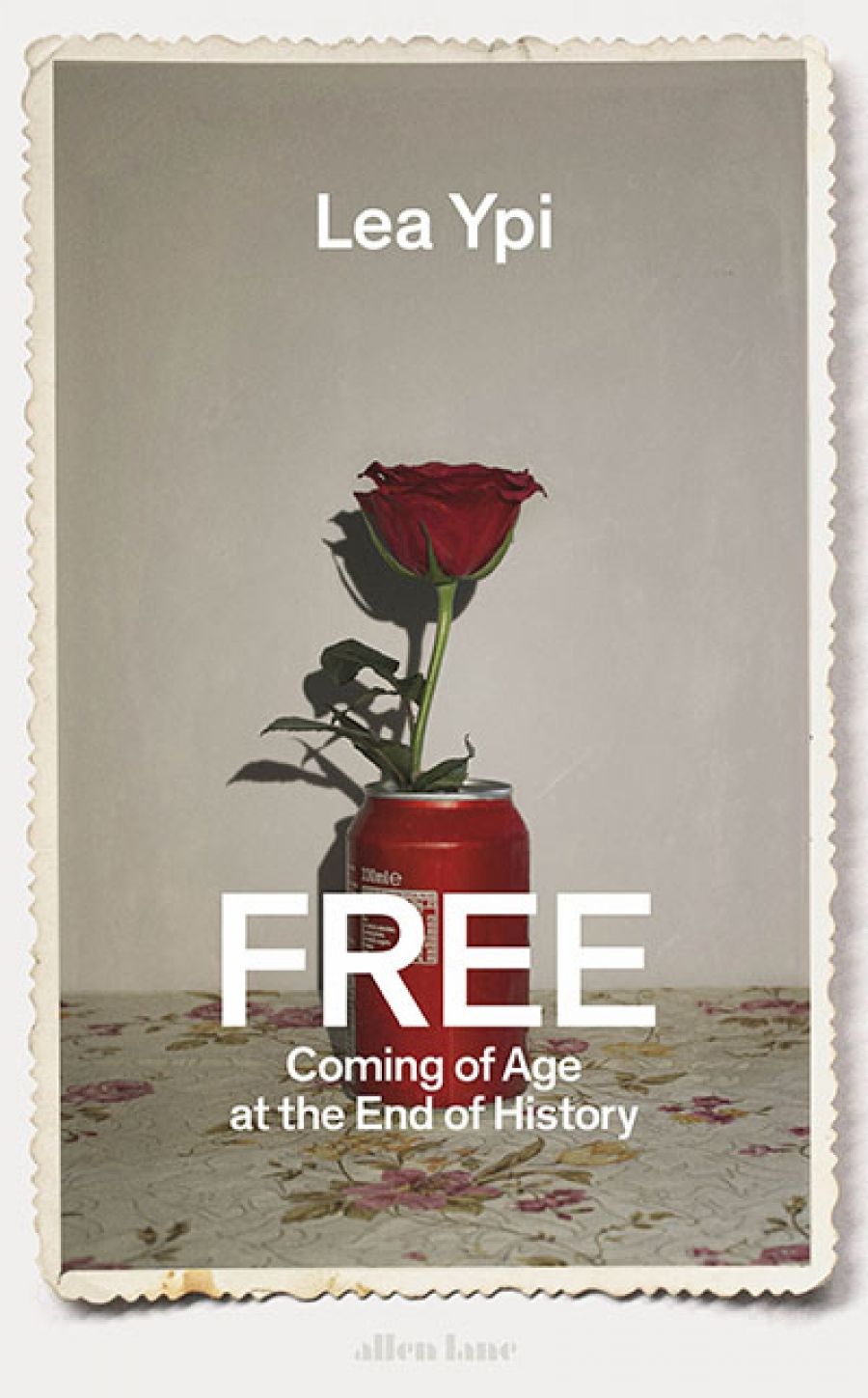

- Book 1 Title: Free

- Book 1 Subtitle: Coming of age at the end of history

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen Lane, $35 pb, 313 pp

The book identifies and explores the gulf between the ideal of socialist freedom in Albania and the lived experience of secrecy and censorship under an oppressive regime. Ypi is a political theorist at the London School of Economics, but Free is unlike her other writings; it is her answer to the hostility and confusion shown by her family to her academic research on Marx and her Marxist politics. Ypi broke the promise to her parents to ‘stay away from Marx’. However, like MacIntyre, Ypi conceives of socialism, through Marx, as the actualisation of human freedom. Free is a stirring personal narrative that understands freedom not just as a matter of government but, following Immanuel Kant, as a moral norm. Despite its misuse, freedom involves a confrontation with the forms of rule that claim to embody it. This book makes sense of Ypi’s broken promise, although now ‘obsolete with time’, as remembrance of what freedom meant to those around her.

Free is a book about transitions. From state-socialist to free-market liberalism and childhood to adulthood, Ypi tells the story of a society changing dramatically. In the early 1980s, Albania was a sealed-off nation, a pristine ‘anti-revisionist’ Stalinist regime. The language of class struggle, anti-imperialism, and the transition from socialism to communism was the ideological ornamentation of a regime with little individual autonomy. Socialism was equated with a freedom and equality that aspired to be deeper and more substantive once the transition to communism was complete. Friends were made through the solidarity of food queues and kept through political secrecy. Oppression and censorship defined life under a one-party state. Starting in December 1990, pro-democracy demonstrations led to the fall of the regime and the introduction of the free market. By 1997, after more than half of the population lost their savings to pyramid schemes set up in the transition, the country was engulfed in a bloody civil war. Profiteering, criminal or otherwise, defined life under liberal capitalism. Yet, in the triumphalist mood of the ‘end of history’, liberal capitalism was often simply equated with freedom. As state socialism fell in 1990, Ypi writes that the language of socialism was the initial casualty:

It was gone not only as an ideal, not only as a system of rule, but also as a category of thought. Only one word was left: freedom. It featured in every speech on television, in every slogan barked out in rage on the streets. When freedom finally arrived, it was like a dish served frozen.

Ypi articulates the failure of both forms of government to live up to the ideals of freedom that they claimed to embody. The word freedom itself had transitioned from one meaning to another radically different idea. If freedom had once denoted social equality, it was now used to support arguments for the freedom of trade, alongside words like ‘shock therapy, sacrifice, property, contract and Western democracy’. Ypi questions the liberal assumption that free markets allow for people to be free.

However, what is remarkable about Ypi’s account is that this philosophical claim is recounted through her matter-of-fact representations of her childhood. Her story is reflective (in the Kantian sense), she teases out and slowly reveals the secrets hidden from her, with the knowledge only the storyteller could know. Childhood events are often marked by confusion and frustration, anxious attempts to piece together fragments of overheard conversations and unexplained occurrences. The young Ypi doesn’t understand why her parents refuse to display a picture of Enver Hoxha in their house, or why she is encouraged by her father not to write about Solidarność in the school newsletter, but instead the village cooperative, which ‘surpassed the target for wheat production set in the current five-year plan’. She is told their life is defined by their ‘biography’, but she doesn’t learn until the regime falls that her family had a complex political history.

While many of her classmates had heroic connections to the anti-fascist resistance during World War II, Ypi was forced to explain every year that she is not related to Xhafer Ypi, Albania’s tenth prime minister. This Ypi played a reactionary role in both the establishment of a monarchy and the fascist Italian occupation of the country. In fact, Ypi unknowingly is related to Xhafer Ypi, but this is kept tightly secret. Later, she discovers that her parent’s frequent discussion of what their relatives studied at university was their code for talking about prison sentences. Her grandfather, a socialist, was imprisoned for fifteen years. It is not until 1990, when the ‘first opposition party was founded [that] my parents revealed the truth, their truth. They said that my country had been an open-air prison for almost a century.’

Learning the truth creates a crisis of meaning for the young Ypi, a crisis inseparable from the fall of the regime. Ypi portrays her family as embodying different ideas of freedom, different norms that guide their reasons and actions. They become engulfed in the pursuit of a freedom previously unknown. Her mother joins the opposition party and becomes consumed with tracking down property her family owned before Hoxha. Ypi’s father is elected as an MP but is ineffectual and demoralised. The so-called transition to freedom was partial and fundamentally limited. The American inflection of the word never lived up to the reality. The transition was disastrous, with high levels of unemployment, poverty, sex trafficking, and organised crime.

While both the historical manifestations of socialism and liberalism betray the ideal of freedom they promise, for Ypi, human beings are free. This insight is gained from Kant and Marx but also from G.W.F. Hegel and Rosa Luxemburg. To be free means acting on reasons that are open to reflection. Our decisions and desires give human action subjectivity, but every decision and desire has a history, which is often formed long before we try to articulate what we want. Those histories confine what is possible for us as agents. What makes us free is our ability to recognise, in ourselves and our institutions, the conditions for an authentically free life and our struggle to achieve it.

Comments powered by CComment