- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The push-pull of the past

- Article Subtitle: A hypnotic trip into outback gothic

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The latest in a new crop of outback gothic fiction, Josh Kemp’s début has everything readers have come to expect from the genre. There’s a messed-up bloke with a past. There’s a lost girl, ten years old and traumatised. There’s plenty of guilt and shame, damaged landscapes, haunted houses, injecting drug use, altered states, brutal acts of violence, and of course, there is the road.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Josh Kemp (photograph via UWA Publishing)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Josh Kemp (photograph via UWA Publishing)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jennifer Mills reviews 'Banjawarn' by Josh Kemp

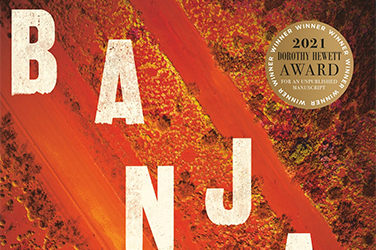

- Book 1 Title: Banjawarn

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $32.99 pb, 416 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/QOxNno

Our main character, Hoyle, is a true crime writer, but after one successful book he has given it up in favour of driving around remote Western Australia in search of redemption, or perhaps an escape from the past – he’s in a push-pull relationship with his personal history. When we meet him, he is perpetually high on PCP, and the dissociative and hallucinogenic effects of the drug reverberate through the evocative desert into which he regularly walks. In Hoyle’s eyes, the landscape is symbolically weighted: the light, the trees, the vast sky, an eagle picking at the carcass of a kangaroo, all seem to hold personal significance. Kemp’s characters are dazzled, confounded, and sometimes crushed by forces greater than themselves.

The story takes off when Hoyle finds and rescues, or perhaps abducts, an abandoned ten-year-old. His driving becomes more purposeful as our broken man looks for a way to do something right for once, to help someone in need. Slowly, we discover why he has this urge to redeem himself.

The West Australian setting is more than a character, it’s the animating spirit of this book. The narrative perspective is sometimes zoomed right out, giving the reader a hovering view of isolated places that seem more sky than land. If the book’s more contemporary details – catching Covid is an outside risk – sometimes detract from this mythical sensibility, they also add to the setting’s vivid sense of isolation and mistrust.

The hallucinatory episodes are sometimes over the top, and there are moments when Kemp seems to be enjoying his own gross spectacle too much. There are many scenes, real or imagined, that are not for the faint of stomach. With the horror genre, sometimes dialling things back has more of an impact; too much gore can tip a reader’s disbelief out of suspension. Fortunately, there is sporadic humour, rural and self-effacing, that provides some relief, and Kemp’s characters are rendered with love, in all their complexity and vulnerability.

It helps that Kemp writes with a compelling voice, the kind you want to follow into dark places, no matter how gruesome things get. He has a way with language that is often delightfully lyrical: at the edge of the Banjawarn homestead, ‘a clutter of gimlets ... fresco the ground’; elsewhere, a possum ‘flexes its little vampire hands’, and I clap mine.

There’s a long tradition behind this kind of fiction in Australia, from the lost and wandering men of Patrick White and Randolph Stow, to the haunted landscapes of Joan Lindsay and the human terrors of Kenneth Cook. More recently, historical fiction like Chris Womersley’s Bereft (2010), or the outback noir of Garry Disher and Jane Harper, stake out nearby ground. Cormac McCarthy is a quoted influence here, and Kemp shares the American recluse’s interest in evil, his ambivalence about redemption, but not his more nihilistic portrayals of human nature.

What’s interesting about Banjawarn is the way it shows the genre developing and diversifying. Unlike some exponents of the outback gothic, Kemp is conscious of the political context of his storytelling and works hard to counter its racist tropes, acknowledging Aboriginal ownership of story, contemporary police violence, and even the destruction of Juukan gorge. Banjawarn is further enriched by Kemp’s willingness to render the most minor of characters fully human, which makes his sparse world lively.

It’s encouraging to see Kemp question himself – even the presumption that violence has to escalate (even with his hand on the throttle). Halfway through this journey, Hoyle wonders if ‘perhaps there were no terrors waiting for him at the end of the road’, a speculation that turns out to be optimistic.

Like ghost stories and westerns, Banjawarn is about justice and is attentive to many forms of injustice: the neglected child, the destructive violence in Western Australia’s history, old poisons left behind in the land. It is even haunted by the spectre of the unethical author. Retribution offers some satisfaction, but it’s incomplete and it opens the way to further violence. The conflation of violence and justice here is very like a western, as the boundaries between good and evil shimmer and dissolve.

Kemp does not confuse that evil with the land. To him and his broken heroes, the country is refuge and teacher, messenger and warning, often hypnotic, a narcotic in itself. Cruelty comes not from the haunted landscape but from human rage.

Horror does have the capacity to soothe. It can be comforting to imagine terrible things, to ride out fears in fiction and come back safe. There’s power in that narrative trajectory. As the evil of Banjawarn escalates, there’s a risk of fatigue; the violent crescendo crashes on beyond its usefulness.

Despite the novel’s brutal events, care and compassion hold it together. There is a genuine feeling for the strength of friendship and the way that traumatised people can find and ease each other’s pain, even with betrayals, even when there seems to be no safe place, no escape from violence or abuse of some description. It offers glimpses of survival and of the power of a chosen family.

One thing about the outback gothic: there’s always more road stretching out into the distance, the landscape so vast it can accommodate infinite possibilities. Banjawarn is a spirited addition to the genre, one which shows it moving with the times and looking to its horizons.

Comments powered by CComment