- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Cultural Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Postmodern kaleidoscope

- Article Subtitle: An accessible guide to postmodern thinking

- Online Only: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

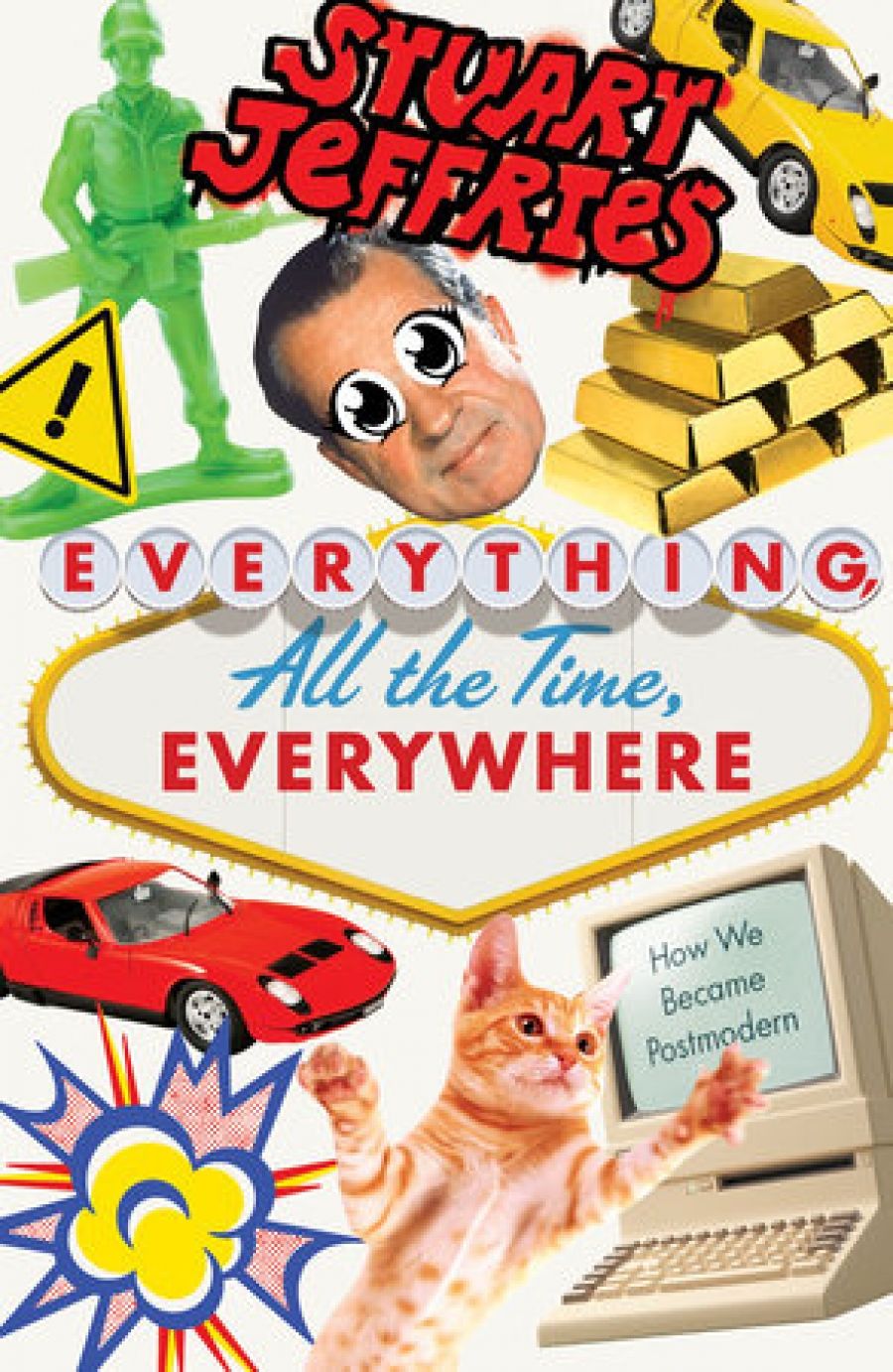

In Everything, All the Time, Everywhere: How we became post-modern, journalist and author Stuart Jeffries explores two hypotheses: that ‘post-modernism originated under the star of neoliberalism’; and that the twin forces of economic neoliberalism and cultural postmodernism combined to shift identities in the global West from citizen to consumer. Jeffries offers a compelling frame through which to examine recent history. Postmodernism’s pluralism can make it seem like a glittering but unwieldy creature; yet, as Jeffries outlines in this book, its influence and contemporaneity with the rise of neoliberalism continue to be important. Jeffries’ approach is to work with, rather than against, the kaleidoscope of postmodernism. Focusing on the years between 1972 and 2001, predominantly in the United States and United Kingdom, Jeffries provides a diverse cross-section of analyses of political and economic movements, popular music, postmodernist art, architecture, Silicon Valley business culture, gender theory, philosophy, hiphop, the Rushdie fatwa, and beyond.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Heather Blakey reviews 'Everything, All the Time, Everywhere: How we became postmodern' by Stuart Jeffries

- Book 1 Title: Everything, All the Time, Everywhere

- Book 1 Subtitle: How we became postmodern

- Book 1 Biblio: Verso Books $39.99 hb, 378 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/LPYYXo

Jeffries is influenced by his reading of the philosophy of Byung-Chul Han, particularly Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and new technologies of power (2017). Jeffries reviewed this work for the Guardian, and some of his musings from that article appear again here. Han’s philosophy is noted for an accessibility that clearly resonates with Jeffries. The structure of Everything, All the Time, Everywhere is such that it provides a door for anyone familiar with David Bowie, the iPod, and Las Vegas to grasp some of the fundamental ideas, events, and philosophies that underpin the ‘postmodernist’ era. Jeffries deftly presents postmodernist philosophy for the casual, or introductory, reader not as a series of isolated arguments but as a lengthy conversation between numerous thinkers across time.

In the introduction, Jeffries sets out several philosophical approaches to conceptualising postmodernism, particularly those of Ludwig Wittgenstein, Daniel Dennett, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Fredric Jameson, and Dick Hebdige. Jeffries’ approach to analysing postmodernism in his case studies seems to borrow a little from each. At times his analyses appear ‘arboreal’ – that is, a ‘grand narrative’ of postmodernism constructed in posterity. This is something Daniel Baksi has noted, writing for The Arts Desk that the book is an attempt to form a ‘chronological origins story for the world of today’. This would likely be irksome to some of the postmodernist thinkers whom Jeffries examines, but I doubt that would ruffle his feathers. In a playful aside on Barthes’ concept of the ‘punctum’ (the ‘personally touching’ detail of a photograph that ‘pricks’ but ‘also bruises’), Jeffries writes: ‘without wishing to be disrespectful to Barthes, who cares about his bruises?’ At the same time, his diverse selection echoes, in a simplified manner, the rhizomatic network structure posited in the work of Deleuze and Guattari. Jeffries explains the rhizome as ‘a map or wide array of attractions and influences with no specific origin’. While this book is not purely a work of applied rhizomatic theory, Deleuze and Guattari’s influence on its structure is clear.

Hebdige considered postmodernism ‘a semiotic black hole, consuming everything but signifying nothing’; at times, this is true of Jeffries’ book. There are moments when the rigour of Jeffries’ analyses slips – likely due to the gargantuan task this book sets itself to complete while remaining accessible – making the point of some sections feel a bit disconnected from fulfilling an argumentative purpose. The brevity can also mean that some examples feel shoehorned into Jeffries’ methodology. In ‘Living for the City, 1981’ and ‘Breaking Binaries, 1989’, Jeffries examines the rise of hiphop in the Bronx and Judith Butler’s work on gender theory through the lens of postmodernism. Both examples are interesting but felt less attentive than they could have been to the complex structures of power that predate neoliberalism, and which are relevant to both these case studies. Jeffries’ reading of Grand Theft Auto is more of a discussion of Max Clifford’s publicity campaign than the game itself. That’s not to say Jeffries’ readings are incorrect, but in their quest for accessibility some nuance may have been lost along the way.

Nonetheless, Everything, All the Time, Everywhere is a thought-provoking book. Jeffries is clear and clever, and alongside chapters on Thatcherism, Silicon Valley, and the Nixon Shock of 1971, his writing on postmodernist architecture and neoliberal city planning is excellent. It is here that Jeffries’ observations on the shift from citizen to consumer are salient and impactful. Byung-Chul Han writes that all his books of philosophy end ‘in a utopian counternarrative’, that they ‘analyse the malaises of our society and propose concepts to overcome them’. Everything, All the Time, Everywhere doesn’t end on such firm suggestions, but on a personal reflection by Jeffries on the built environment in his local borough of Islington, London, in an afterword: ‘Ghost Modernism’. Of all the chapters in this book, the ones that talk about London tend to be most poignant. The clash between London’s rich cultural history and the stresses that neoliberalism has placed upon the city is a familiar one for anyone who has spent an extended time living there. Jeffries’ desire to convey understanding in this book seems to be driven by a deep affection for London as well as a desire to better perceive its ‘postmodern ghosts’.

Comments powered by CComment