- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Shadowboxing

- Article Subtitle: The story of an American pugilist

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In David Whish-Wilson’s new historical novel, The Sawdust House, it’s 1856 San Francisco, where the citizen-led Committee of Vigilance has convened to purge foreign undesirables from a city populace swollen beyond control by the gold rush. Of course, armed nativists ‘enthralled by their own performance’ are a common feature of U.S. history, from the Virginian lynch mobs of the late 1700s to that guy in the fuzzy Viking hat parading around the Capitol Building just last year. In an intriguing twist, however, the pitchforks are aimed this time at those ‘vermin from some hellish southern continent’, aka Australians, particularly a criminal element who congregate in a lawless quarter nicknamed Sydney-town.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

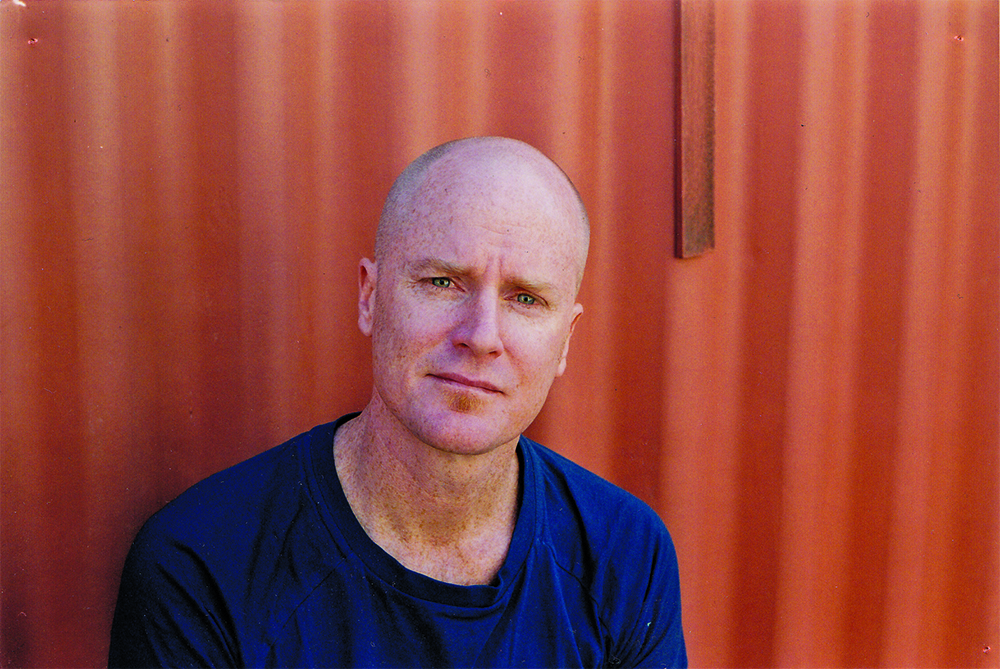

- Article Hero Image Caption: David Whish-Wilson (photograph via Fremantle Press)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): David Whish-Wilson (photograph via Fremantle Press)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Alex Cothren reviews 'The Sawdust House' by David Whish-Wilson

- Book 1 Title: The Sawdust House

- Book 1 Biblio: Fremantle Press, $32.99 pb, 304 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/7mBoGy

Whish-Wilson has dipped into this fascinating pocket of history before. His 2018 novel, The Coves, was a rollicking adventure of a young boy and his dog trying their best to sidestep the brutal violence exploding – in Cormac McCarthy-like bursts of lyricism – around each corner of Sydney-town. The Sawdust House is equally gripping, but the way it weaves fact and fiction is more complex than that earlier work. It is both a stylish retelling of one extraordinary life and an investigation into the truths that slip through history’s net, sinking to depths only imagination can plunge.

The protagonist is a real-life boxer who went by many aliases but was most commonly known as James ‘Yankee’ Sullivan. When we first meet Sullivan, he is being held in a squalid prison cell, charged by the Committee with racketeering and election fraud on the behalf of a local Democrat. Thraldom is nothing new to Sullivan, born in an Irish town so controlled by the English that ‘even the pigs are protestant’ before later enduring servitude in remote Australian penal colonies, where ‘it were a rare morning when a man weren’t flogged to death’. He still managed to carve out a life of remarkable accomplishment, including winning the English middleweight boxing championship, introducing pugilism to the United States, and counting Walt Whitman as a friend.

Across five days, Sullivan relates moments from this bulging biography to a Mormon journalist, Thomas Crane, whose own secrets are teased out along the way. This tidy framing device allows Whish-Wilson to dole out chunks of his research to Sullivan, the great mass of which might have otherwise passed into the flow of fiction about as smoothly as a kidney stone. Sullivan roams back and forth across his life, pressing on a memory only until its recollection becomes too painful: ‘I remember everything, but that doesn’t mean I have the words.’ When Sullivan does speak, his voice takes some acclimatising to. At times, it is grammatically broken – ‘we were poor hungry dirty’ – at others, a touch highfalutin: ‘is there a soul within me or am I merely an empty chamber that rings out with endless questions for which there are no answers?’ Some might not accept the veracity of an uneducated boxer, even one who shared the occasional whiskey with Whitman, arranging a sentence so. But this is nothing compared to the portions of the novel where Whish-Wilson dives into Sullivan’s inner life, finding nightmares about vicious crow-people and feverish meditations on violence: ‘it is myself that my fists annihilate, and his pain that I feel, and both of our lives have led to this pure moment’.

These wild bouts of speculation are reminiscent of the hallucinations that Benjamin Labatut dreamt up for Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schrödinger, and other geniuses in his collection, When We Cease to Understand the World (2020). Reviewing that book for The New Yorker, Ruth Franklin fretted about the destabilising effect of these imaginative excursions: ‘If fiction and fact are indistinguishable in any meaningful way, how are we to find language for those things we know to be true?’ In response, The Sawdust House seems to argue that ‘true’ and ‘fact’ are not synonymous, and that any language treating them as such is faulty.

The novel’s distrust of official sources is immediately flagged when Crane admits that his editor wants a ‘penny-dreadful story’ for his Murdochish newspaper whose ‘hastily stitched spine fans out beneath the humidity of the reader’s panting breath’. Sullivan is not the ‘jug-eared low-browed buck-tooth bog-Irish knuckle-dragger’ Crane was made to expect, but instead a melancholic man with a soft voice ‘like the song of a new species of bird’. The great irony of Sullivan’s life is that he has pulled himself out of poverty through boxing, yet he detests the sport, his first victory leaving him ‘sick and ashamed ... certain that I never wanted to fight again’. This gap between Sullivan and his public face is underlined by the real boxing records and magazine articles scattered throughout text, the sum of which reveal nothing of the complex soul we come to know. When Crane mentions reading The Life and Battles of Yankee Sullivan, a real book published in 1854, Sullivan dismisses its supposed biographical authority as just ‘a veil of clever words as though my combat and bleeding were but a poem or a legal contract or a mathematical problem to be understood’.

How did Whish-Wilson come to such a dizzying scenario, with his fictionalised version of a real person denouncing a text that Whish-Wilson must have partly used in creation of said character? I like to imagine that as he dutifully read The Life and Battles of Yankee Sullivan, a dark little door opened up in the back of Whish-Wilson’s mind, through which Sullivan’s true, bird-like voice began to trill, telling him, as Sullivan tells Crane, to ‘write it down like I say it and no other way’. But who knows; I’m just speculating.

Comments powered by CComment