- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Wake up to yourself!

- Article Subtitle: A vivid new translation of Dante

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In Italy, Dante is known as il sommo poeta (‘the supreme poet’). Ironically, such reverence obscures the creative personality. We know Dante responded to the shock of being exiled from Florence in 1302 by writing a visionary poem of hell, purgatory, and paradise, in which his tormented life and feuding world were set right – but why did he do it? With little biographical evidence and no original manuscripts of the Commedia surviving, most translators and commentators prefer to concentrate on Dante’s myriad historical and theological sources. It takes a simple shift of logic to search them for the missing psychological evidence.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

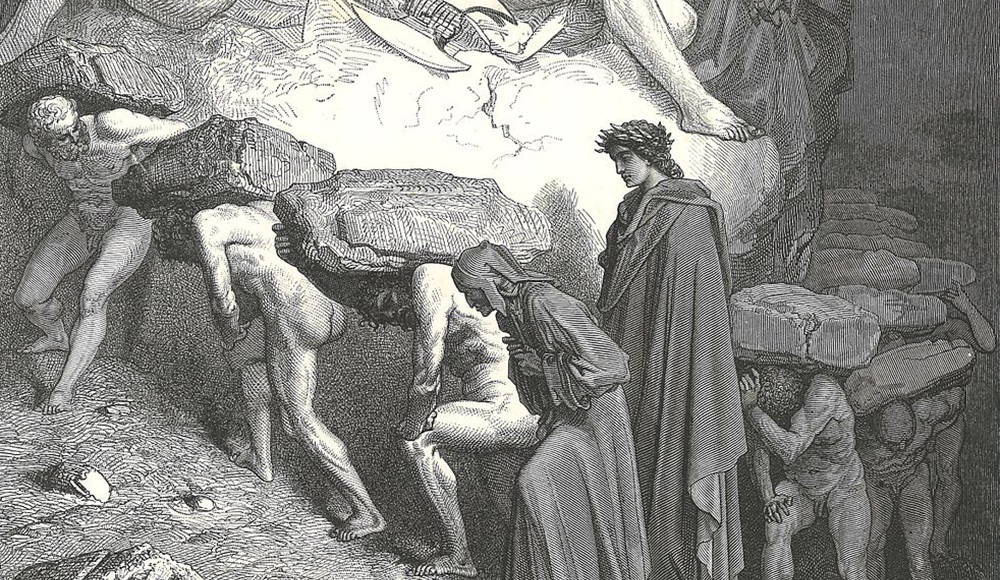

- Article Hero Image Caption: A detail from a print by Gustave Dore depicting Purgatory from the <em>Divine Comedy</em> by Dante Alighieri (Wikimedia Commons)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): A detail from a print by Gustave Dore depicting Purgatory from the <em>Divine Comedy</em> by Dante Alighieri (Wikimedia Commons)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Theodore Ell reviews 'Purgatorio' by Dante Alighieri, translated by D.M. Black

- Book 1 Title: Purgatorio

- Book 1 Biblio: NYRB Classics, $32.99 pb, 483 pp

It is the marvel of this edition of Purgatorio that translator D.M. Black presents a vivid portrait of Dante’s mind. This edition complements NYRB Classics’ 2004 edition of the Inferno, translated by the late Ciaran Carson. (Who will do NYRB’s Paradiso?) A poet with a background in philosophy, Black has also had a distinguished career as a psychoanalyst. His edition of Purgatorio exercises all three disciplines at once, mounting a psychoanalytic enquiry into the poetic suggestions of trauma, obsessions, fantasies, and repression. It is a truism that Dante must have experienced all these facets of mental life (though he could not have conceived of them in those terms). But it is uncommon for a translator to credit them as Dante’s reasons for writing, seek out their traces in the text – in the qualities of its drama, narration, symbolism, philosophy, language – and construe the psychological and emotional origins of Dante’s ‘divine’ construct.

Black draws parallels between the therapeutic aims of psychoanalysis and Dante’s depictions of the redemption of souls. Black argues that what Dante calls ‘the soul’ finds its modern equivalent in ‘the mind’ or ‘the person’, that Dante’s idea of ‘sin’ is what we know as ‘motivation’, and that Dante’s idea of ‘discernment’, clear-sightedness, or purity of intent is, for us, ‘insight’. In Purgatorio, the middle book of the Commedia, Dante and Virgil climb the mountain on which souls are purged of their sins in preparation for paradise. At the summit, Dante is reunited with the soul of his lost love, Beatrice. Black has chosen to translate only Purgatorio because he believes it carries the most uplifting and urgent message of the Commedia: wake up to yourself.

Black observes that Dante’s Purgatorio is not merely a ‘detention’ zone, where souls simply await purification. The punishments demand an effort to understand sin: that is, to recognise motivation and change it. In Inferno, souls are ‘stuck’, unable to change. In Purgatorio, souls are redeemed because they achieve self-knowledge. Black finds an exact equivalent in the mission of psychoanalysis, as articulated by Sigmund Freud: ‘to make the unconscious conscious’, to understand one’s motivations and turn their conflict into coherence. For Dante, as for the psychoanalyst, there is no formula for achieving this. For Black, the punishments that Dante tailored to each sin show ‘there is a right configuration for ‘every soul.’

Unlike in Inferno and Paradiso, the geography and mechanisms of Purgatorio are Dante’s inventions. Black draws a fascinating parallel between Dante’s concept of allegory, as expressed in his treatise Convivio (1304–7), and the ways in which psychoanalysts read the images and symbols through which the unconscious communicates with the consciousness. Black describes the allegorical pattern of Purgatorio – the climbing of the mountain, punishments tailored to sins, the reshaping of the self – as Dante’s projection of his struggle to understand his own failings and overcome his self-resentment. This is a bold claim that rests on inferences about Dante’s unconscious motives. His descriptions of passing through the rivers of Lethe and Eunoè, forgetting sin and remembering his better self, are potent dramatisations of mental renewal – but could reuniting with Beatrice really revive Dante’s repressed grief for another woman, his long-dead mother? Black believes so, finding clues in Dante’s description of their meeting and Beatrice’s rebuke of his wavering faith in her (Canto XXX). Dante’s awe at seeing her turns to shame – he cannot even look at his own reflection in the water – just as a psychoanalyst would expect, if Dante were carrying unresolved trauma connected to love for women.

Whether or not we agree fully with this speculation, Black’s approach is humane and is derived in good faith from evidence in the text. In turn, Black elucidates the text wonderfully. His opening and closing essays, and his notes at the end of each Canto, are as energetic as they are thorough. More than a glossary of medieval ideas, Black’s commentary integrates each explanation into the structure and development of Dante’s psychological drama.

Interpreting the Purgatorio is only half of Black’s task. A translator must keep faith not only with the meaning but also the experience of the text. Black has opted for a verse translation, wisely refraining from rhyme but employing a loose and unobtrusive pentameter and keeping Dante’s tercet, a design that maintains momentum strongly. Black’s rule was to stay ‘as close as possible to the movement of Dante’s thought’, rather than seek pedantic parallel meanings. More than pace or rhythm, ‘movement’ here means drive, agility, immediacy of detail, and, most importantly, an impression of restless mental activity. Each line and tercet of Black’s verse is calculated to match Dante’s in conveying the cascade and interlacing of thoughts, through and around the narrative. Black has a gift for condensed and aphoristic single lines – ‘that noble shoot that sprang from humble grass’ (Canto XIV), ‘you gather darkness from the light itself!’ (Canto XV) – and his immense labour appears, in most places, effortless. Even the passages of theological or moral discourse skip along, thanks to a deft use of monosyllables. Unfortunately, the focus on ‘texture and movement’ creates some results that upset tone and register. Black acknowledges the influence of J.D. Sinclair’s biblically inflected prose translation (OUP, 1939–46) on his approach to passages of dramatic weight and moral gravity, but frequently, and inconsistently, for the sake of metre, he resorts to contractions – ‘it’s,’ ‘you’re,’ ‘can’t’, and the like – which sound awkward when spoken by solemn characters. Black also undercuts himself through the grating use of modern slang. Early on, Dante and Virgil search for a ‘doable’ path up the mountain, and in the next Canto the lethargic Belacqua scoffs, ‘OK, you climb, if you’re so energetic!’ In compensation, Black translates some of Dante’s most decisive scenes superbly. Dante’s reunion with Beatrice is as tense and poignant as it should be, and Dante’s speech about the vocation of poetry (in Canto XXIV) is as confident and straightforward in Black’s English as in Dante’s Italian, rendering the crucial phrase ‘a quel modo / ch’è ditta dentro vo significando’ as, ‘I go, / as he [Love] commands me inwardly, making meaning.’

The overall poetic quality of the translation is impressive in an edition that already does more than most to portray Dante as a thinking individual and to bring a general audience closer to him. Our contact with Dante can only be fleeting, but Black makes him as hauntingly present as the departed souls whom Dante himself glimpses. As Black puts it in Canto XXVI, ‘He vanished then in the refining fire.’

Comments powered by CComment