- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Avec everything

- Article Subtitle: Biographical shards of James Ivory

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Call me Ismail,’ it could plausibly begin: a screenplay not of Herman Melville’s novel Moby-Dick but of the real-life relationship between two filmmakers renowned for their adaptations of a string of other classic novels. Ismail Merchant first met James Ivory on the steps of the Indian consulate in Manhattan in 1961. ‘Call me by your name,’ the Ivory character might wittily retort in this imagined biopic. That, of course, was to be the title of the film scripted by Ivory nearly a decade and a half after Merchant’s death in 2005, but it captures something of the symbiotic nature of their partnership.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

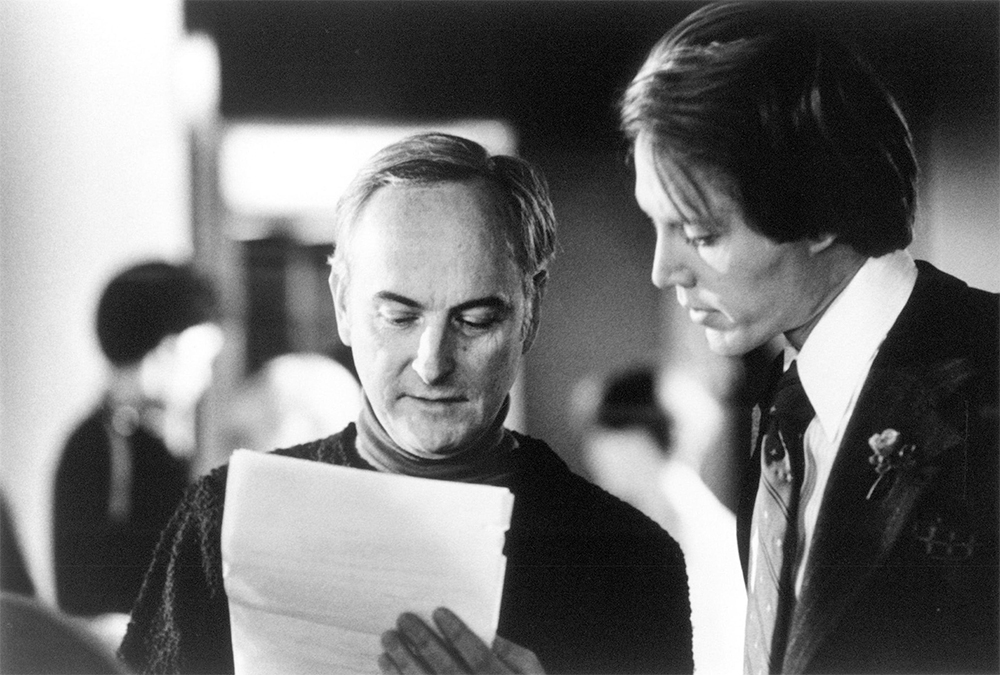

- Article Hero Image Caption: Director James Ivory with Christopher Walken on the set of <em>Roseland</em>, 1977 (photograph by Merchant Ivory/Alamy)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Director James Ivory with Christopher Walken on the set of <em>Roseland</em>, 1977 (photograph by Merchant Ivory/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Ian Britain reviews 'Solid Ivory' by James Ivory

- Book 1 Title: Solid Ivory

- Book 1 Biblio: Corsair, $34.99 pb, 399 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/DVMnRy

‘Our collaboration is not exclusive, and sometimes we work independently of each other,’ Merchant noted in his autobiography (My Passage from India, 2002). And there were other stalwart members of their creative team, most notably Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. (‘She writes, I direct and Ismael produces,’ as Ivory noted elsewhere.) Yet from the beginning it was the men’s names that were foregrounded, and indissolubly wedded, in the label chosen for their production company: ‘Merchant Ivory Productions’. This label stuck even after Merchant’s death, when Ivory directed, with a different producer, The City of Your Final Destination (2009), adapted by Jhabvala from a novel of that title by Peter Cameron.

Had Merchant lived longer, they might have actually married, as that day of their initial meeting in New York was also the beginning of a lifelong romance – lifelong for Merchant, at least, and every bit as passionate as that of Oliver and Elio in Call Me By Your Name (Luca Guadagnino, 2017). Again, as in their professional life, this was not an exclusive relationship, but while there were infidelities or infatuations with others on both sides these were never to threaten the foundations of their personal bond: ‘I was always there and he was always there,’ Ivory staunchly affirms.

We learn most of these intimate details from Solid Ivory. Parts of it have been published in earlier and different formats, though generally the less racy parts. After spending much of his life ‘trying to be discreet’ – particularly on behalf of Merchant, who could not risk alienating his ‘conservative Muslim family’ – Ivory seems to have decided in his nineties to let it all hang out, as it were, about his sexual past. The more physical or anatomical side to his relationship with his long-term partner is still kept somewhat under wraps but it’s avec, not sans, everything when it comes to recounting his other liaisons: mouths, hands, feet, and many a ‘memorable dick’, erect or flaccid, cut or uncut. (While Ivory’s preference was always for the circumcised variety, he made an exception in the case of writer and sexual adventurer Bruce Chatwin, with whom he had perhaps his longest dalliance and to whom he devotes one of the longest chapters.)

As he suggests, we shouldn’t be entirely surprised or shocked by such details if we know the Merchant–Ivory films well enough. Some of these appear to luxuriate in a super-refined, elegant, ‘period’ milieu that has led one fellow director to categorise them as ‘the Laura Ashley school of filmmaking’. It’s a witty observation, but to dismiss them in this fashion is to obscure their rawer, raunchier moments as well as their deeper emotional textures. That well-known chain of stores was unlikely to employ or display full-frontal nudes, as Ivory and Merchant dared to do in at least two of their adaptations: A Room With A View (1985) and Maurice (1987). The mise en scène in both of these films is exquisitely decorated, but, when fleshly candour is called for, they are never ‘decorous’ in the way that Ivory describes the evasive panning shots of the sex scenes in Call Me By Your Name. He claims that if the opportunity of co-directing that movie had not been arbitrarily taken away from him, he would have handled those sequences far less ‘blandly’.

Ivory seizes the opportunity of his new book to settle other such scores with disobliging colleagues or to rehearse old grievances against carping critics and difficult divas. He or his designated ‘editor’ – the same Peter Cameron who wrote the novel The City of Your Final Destination (2002) – has dredged up earlier articles, diary entries, and letters to complement freshly written chapters of memoir. ‘Portraits’, as they are called here, of Raquel Welch and Vanessa Redgrave are as unvarnished, as free from any starry-eyed deference, as when they first appeared in the 1970s or 1980s. Even at their most blistering, however, they are not devoid of sympathy and a certain sense of awe. And there are many, many more grateful and generous-spirited sketches of less prima-donna-ish workers on Merchant–Ivory films, largely from behind the scenes.

As we learn only in the last chapter, the book’s title, Solid Ivory, is derived from the pen-name its author adopted when a gossip columnist for the newspaper at his high school in Oregon, and that he simultaneously used as a title for a comedy routine he performed at school assemblies. A more fitting title for the book, given its fragmentary structure, might have been Shards of Ivory. (Compare Jhabvala’s 1995 novel, Shards of Memory.) Cameron’s editing of these bits and pieces of a life is savvy and stylish, but the truncations and gaps in the narrative do leave a historian or film-buff yearning for a more cohesive, thoroughgoing account. Charming though it might be, the biopic I fancifully envisioned at the start of this review wouldn’t satisfy this desire. What we need now is a scholarly biography – or joint biography of Ivory, Merchant, and Jhabvala – based on all of their writings as well as their films and on the Ivory archive at the Knight Library of the University of Oregon.

Comments powered by CComment