- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Bess and Kathleen

- Article Subtitle: Dominique Wilson’s new novel

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Dominique Wilson’s new novel is another foray into the field of historical fiction. Her two previous novels deal with the pain of living through periods of civil strife and migration, and cover long periods of time and several cultures: The Yellow Papers (2014) is set in China and Australia from the 1870s to the 1970s, while That Devil’s Madness (2016) moves from Paris to Algiers to Australia and back from the 1890s to 1970s.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Susan Sheridan reviews 'Orphan Rock' by Dominique Wilson

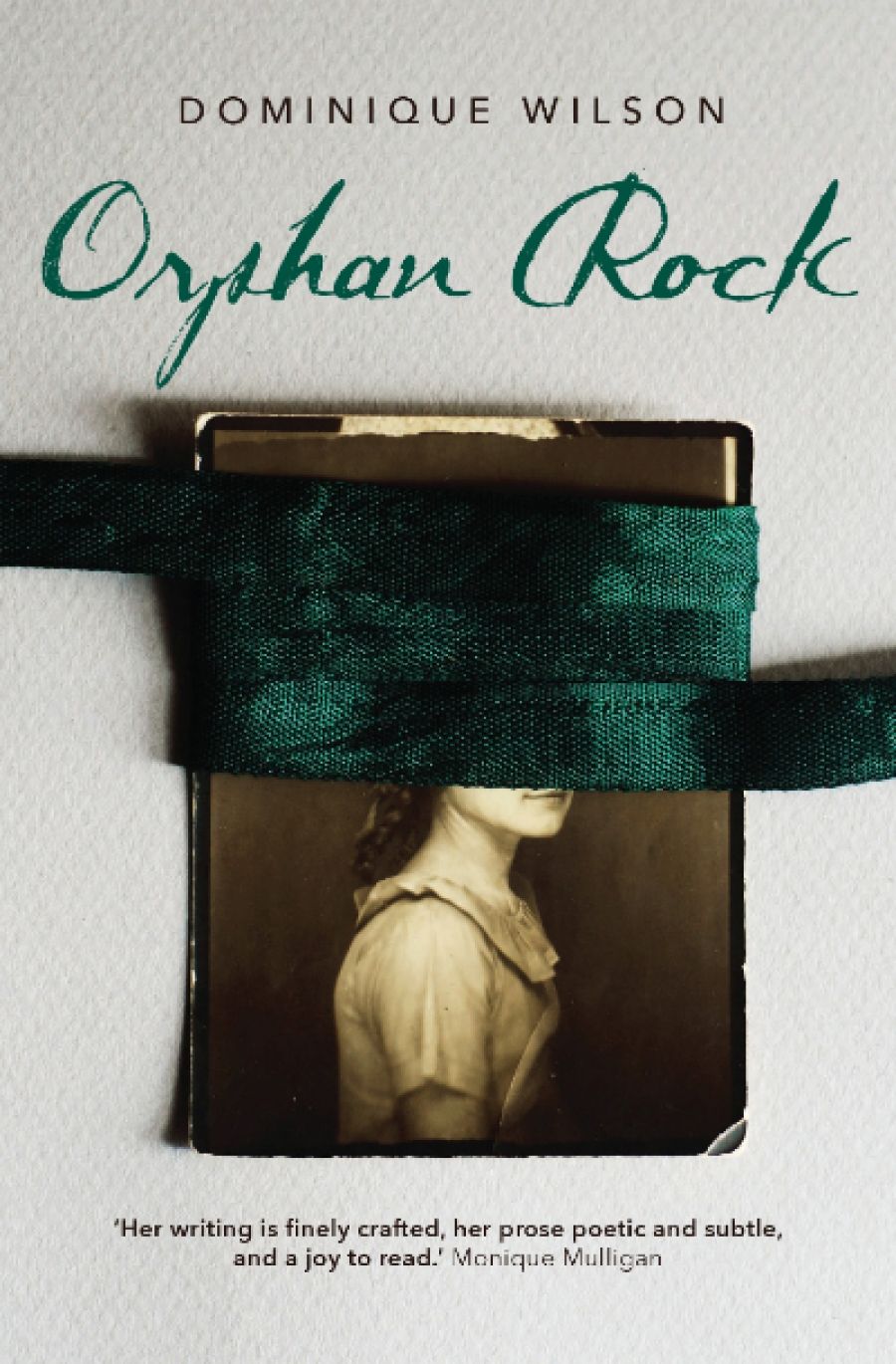

- Book 1 Title: Orphan Rock

- Book 1 Biblio: Transit Lounge, $32.99 pb, 484 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/qnGE2L

Orphan Rock, covering the period from about 1870 to 1941, is like an animated dictionary of Sydney: it features familiar places, like the Botanical Gardens and Callan Park Mental Hospital, as well as some famous Sydney personages from the past: feminist journalist Louisa Lawson and her paper, The Dawn; philanthropist and defender of the Chinese community, Quong Tart; and the notorious Darlinghurst madam Tilly Devine.

With these features, and attention to issues of the time ranging from women’s rights to anti-Chinese riots, from economic depression to public health concerns about syphilis and smallpox, the novel nevertheless holds its two main characters front and centre: Bess, introduced as a little girl in the Parramatta Orphanage; then, after her death, her daughter, Kathleen.

Orphan Rock begins with Bess being taken from the orphanage and brought to a comfortable home in Phillip Street in the city to live with a mother she never knew existed (a woman ironically named Mercy) and stepfather, Cornelius. Life with a delinquent mother and a kindly but naïve stepfather, who sees to it that she has some education, comes to an abrupt end when Bess’s teenage rebellion against her mother coincides with Cornelius’s sudden departure to undergo what readers know (but Bess never discovers) is a lengthy treatment for syphilis. From then on, Bess’s life encompasses the whole gamut of women’s oppression: maternal rejection, the constant struggle to hang onto respectability, limited and ill-paid employment, the uncharted territory of marriage, unfaithful husband, syphilis and madness, death of husband and child, periods of desperate poverty. Her life includes a few positives – a faithful friend, a helpful teacher, a gentle sexual initiation, one or two kind and devoted men. More than anything, Orphan Rock demonstrates the precariousness of women’s lives, especially in female-headed households.

Dominique Wilson (photograph via Transit Lounge)

Dominique Wilson (photograph via Transit Lounge)

Her daughter’s life is similarly precarious, despite a more secure start as the beloved only child of a comfortably-off middle-class couple. She, too, is orphaned when her parents are killed in a motor accident. She struggles as a single mother to raise her son during the Depression years. Like her mother before her, she has the support during this time of Lottie Li, Bess’s friend from her Parramatta days, whose Chinese husband and children were tragically lost to her after the Boxer Rebellion. Also like her mother, Kathleen is at first loath to accept the love offered her by a good man. But at the end of the novel, when World War II has begun, and readers learn that the new husband is assigned to the HMAS Sydney, we know that her life is about to be wrecked yet again.

This pattern of rags to riches to rags again, both materially and psychologically, sets a narrative rhythm that is powerfully evocative of life’s precariousness, but it tends to limit the novelist’s capacity to develop her characters. We are always moving on to the next stage, the next crisis. As well, there is little differentiation between Kathleen and her mother as characters: they suffer the fate of women, of scrambling for a living and mistrusting – with reason – the blandishments of men. Yet one might have expected Kathleen, born in the 1890s and more worldly (having spent several years in Paris as a young woman staying with her mother’s art-loving lesbian friend), to see things somewhat differently from her mother – that she might resist the rules of respectability rather than falling victim to them.

Kathleen’s sojourn in Paris allows Wilson to focus for a while on French culture, which has been a recurring theme in the Sydney story, and to draw on her own culture of origin, having been born in Algeria to French parents and migrating to Australia as a child. Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables (1862) is an important linking device in this episodic novel. Both Bess and Kathleen read and reread Hugo’s story; they recall its heroines, Fantine and her daughter Cosette, as they try in vain to hide the stigma of illegitimacy and are flung into the depths of poverty or lose their fragile social respectability.

What kind of a historical novel is Orphan Rock? It is not in the nineteenth-century tradition of epics that encompassed a whole society in crisis, like Stendhal’s The Red and the Black. Nor is it the kind of popular romantic saga so familiar to Australian readers, like Ernestine Hill’s My Love Must Wait, nor a critical historical novel of the kind that sets out to challenge national myths, like Thea Astley’s A Kindness Cup.

Rather, Wilson’s sense of history seems to be shaped by a commitment to ‘history from below’, a history of everyday life as it affected oppressed people: the destitute, the orphaned, the women seduced and abandoned, the ethnic and sexual minorities cut out of the social contract. The ‘orphan’ in the novel’s title evokes this sense of being cut loose from the social fabric, a feeling that Wilson’s characters experience again and again. They are the dispossessed, les misérables.

Comments powered by CComment