- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Lily and Janks

- Article Subtitle: Paddy O'Reilly’s new novel

- Online Only: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Other Houses opens with its central character, Lily, cruising a drug-riddled suburb in search of her missing partner, Janks, who has disappeared, leaving her and their daughter, Jewelee, to fend for themselves. From the outset, Other Houses is grounded in Melbourne: from the suburban streets that Lily traverses late at night to escape her trauma to the highways that Janks drives along on a doomed mission as a ‘courier of misery’. Suburbs with names reminiscent of big American cities like Dallas have none of the glitz and glamour of their famous namesakes; they are steeped in substance abuse, poverty, and hopelessness.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

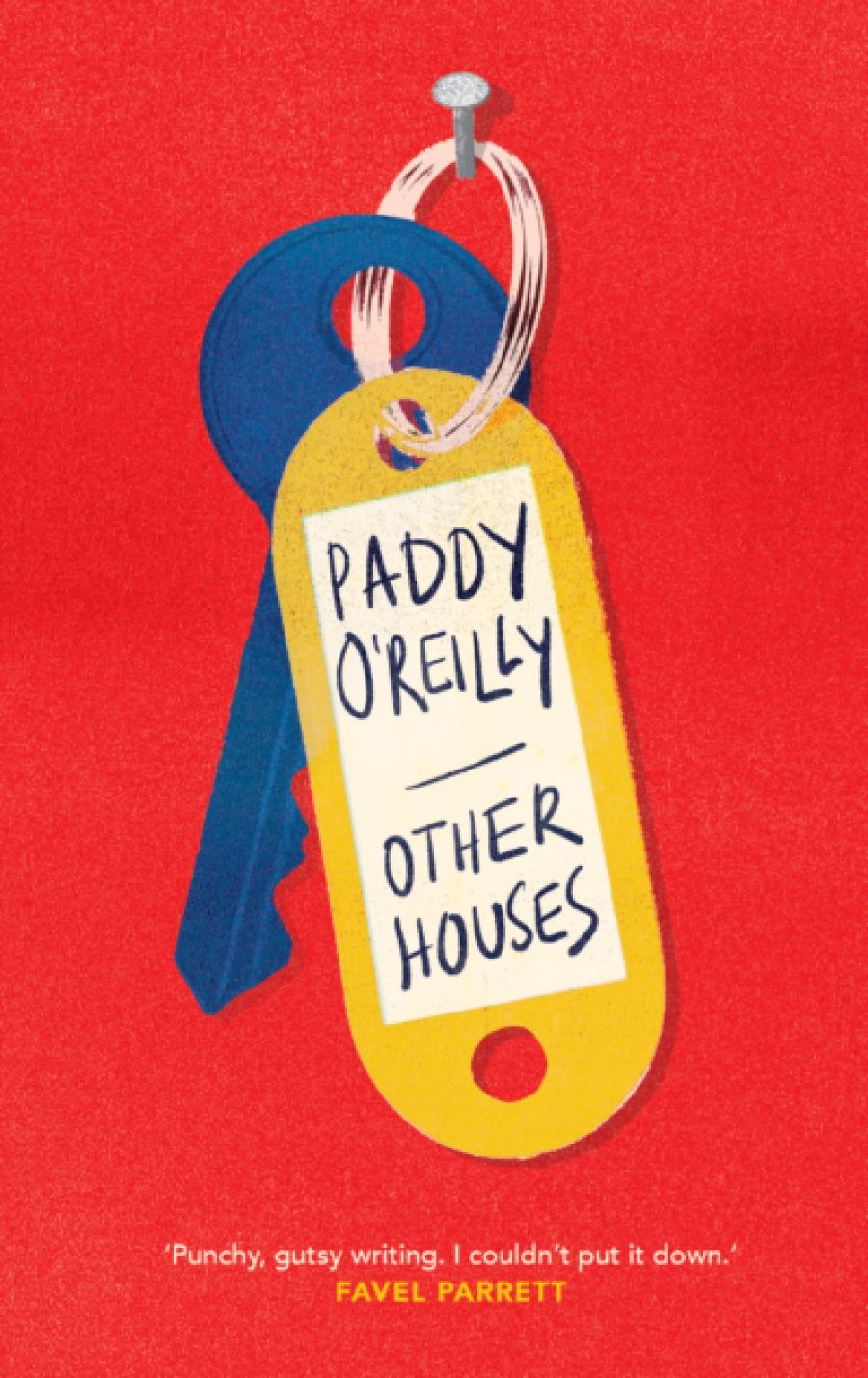

- Book 1 Title: Other Houses

- Book 1 Biblio: Affirm Press, $32.99 pb, 252 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/RyDDO9

Other Houses is relentless in its abject depiction of the cycle of substance abuse and poverty, from heroin user Stevo slapping ‘the inside of his elbow until a weak blue thread’ appears so that he can draw blood in an ill-advised scare tactic, to the ‘food wrappers and empty drink cans and cigarette butts composting in a thick sticky layer’ on a decaying car floor.

While Lily and Janks’s relationship is shown only through their memories, their constant search for one another drives the novel. Lily’s tireless search for Janks, despite the danger hinted at by his disappearance, and the unfurling horror that he finds himself embroiled in, is interspersed with her observations about the houses she cleans with her friend Shannon. By positioning Lily and Shannon as cleaners, O’Reilly opens up a world of contrasting fortunes – the houses of their middle-to-upper class clients are simultaneously full of expensive almond meal, apricot Laminex benches, heavy Egyptian cotton sheets, as well as puddles of piss and coils of excrement.

O’Reilly is adept at depicting the drudgery, and occasional futility, of the labour that is often performed by working-class women, whether in their underpaid jobs or in the unpaid domestic sphere where there isn’t any payment whatsoever, while also according a magical quality to the act of cleaning people’s homes. ‘There’s something witchy about what we do, Shannon and me. Some crone magic, a spell of clean, a whisk of scent, our crooked wands bewitching a house into a welcome,’ Lily reflects as she and Shannon restore a particular house to cleanliness.

But respect and romanticisation are not the same. The premise of O’Reilly’s last novel, The Wonders (2014), is turned on its head. Instead of chronicling ordinary bodies transfigured into fantastical ones, Other Houses does the opposite: ordinary bodies are rendered even more wretched simply by existing. ‘So much of what we do is cleaning up the leakages from bodies. We make everything clean and proper but the bodies can’t contain themselves and out they erupt again. The insides want to come to the outside, the outside is always seeping inside,’ Lily muses to herself as she recollects the time she caught gastro in a client’s bathroom.

O’Reilly is fixated on the demarcation of boundaries: those between the body and the environment, the middle class and the working class, the past and the present. When Janks disappears, Lily worries he ‘might have drifted back over the boundary we’d marked so clearly in our minds’.

There’s a level of subterfuge in the way O’Reilly describes Lily, Janks, and Jewelee obscuring their ascent from the working-class suburb of ‘Broadie’ into the worst house on the best street in Northcote. Unable to afford dental work, Lily returns people’s kindness with a ‘closed-lip smile, practised over decades’, and studiously keeps up with the news until a middle-class mother tells her that she only watches cooking shows because the news is too ‘depressing’. Lily and Janks, fearing judgement, drive to the shopping centre to discard their pizza boxes and stubbies and to bin their holey jeans, only to find they’re in vogue a few years later. In a telling argument between Jewelee and Lily in the second half of the book, the former complains about how they eat stir-fries or pasta bakes every night, unlike her friends’ dinners of hand-crafted spring rolls and home-baked chocolate biscuits. The family’s adoption of a new way of being and their near-constant negotiation of their own identities is likened to ‘trying to squeeze out of [their] own skins like cheap sausage meat’.

Like Jennifer Down’s protagonist Maggie in Bodies of Light (2021), Lily finds refuge in novels, despite a chequered history of schooling. Her first-person narrated chapters are imbued with exquisite detail. Despite a sense of predestination characterising the narrative, the characters’ suffering never feels superfluous. Moments of humour and levity punctuate the direst situations, and the indignities portrayed in Other Houses add to the verisimilitude of the characters’ struggle to stay afloat, more than any gratuitously detailed suffering could. When Lily is distributing flyers concerning Janks’s whereabouts, a homeless man uses them for insulation, because no one reads newspapers anymore. Lily and Janks’s precarious existence is encapsulated by their ‘rental damp and rot, clothes that fall apart, bank accounts that bounce between payday and zero’. The class discrepancy that exists between Lily and Shannon and their clients is captured in Lily’s stark observation, ‘Of course they must make their own bread.’

At one point, it seems as though O’Reilly might render the novel’s overarching moral conundrum obsolete, but ultimately, this possibility is never realised. In the end, the book’s empathy for its characters prevents it from devolving into a narrative of endless trauma and suffering, when the only things worthy of contempt are the structural injustices that render the choices the characters make not much of a choice at all.

Comments powered by CComment