- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Technology

- Review Article: Yes

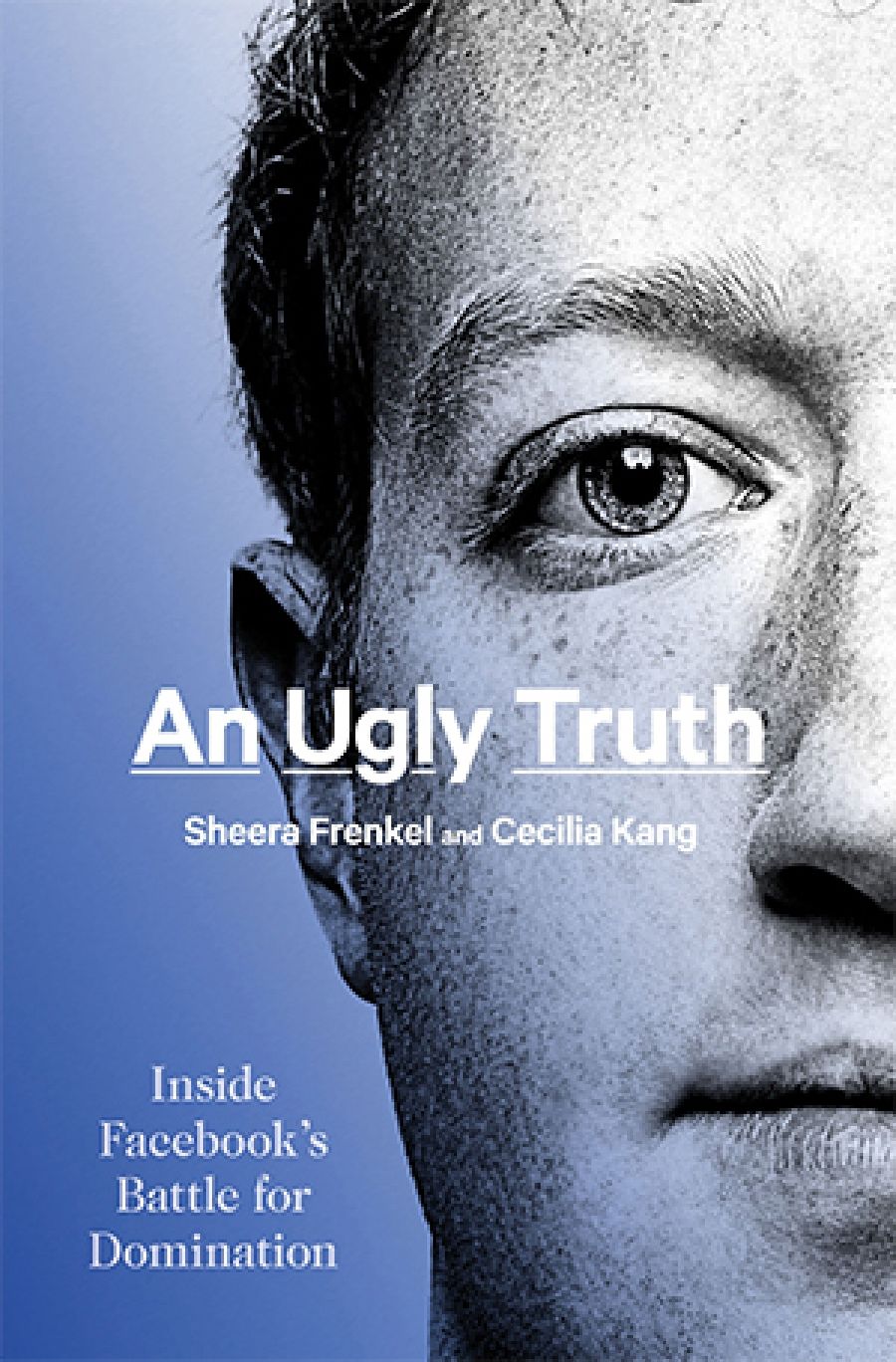

- Article Title: ‘Dumb fucks’

- Article Subtitle: Facebook’s long record of denial and disdain

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Sealand calls itself a micronation. No one else does. It’s easy to see why: the ‘kingdom’ is little more than a glorified helipad. It rises from the North Sea off the coast of Suffolk like a Greek version of the letter π rendered out of concrete and steel – the sole survivor of a series of Maunsell forts built to shoot down Nazi Kriegsmarine aircraft during World War II. Abandoned by Britain in the 1950s, the fort was hijacked by pirate radio broadcaster Paddy Roy Bates in the 1960s and renamed the Principality of Sealand. Bates crowned himself ‘prince regent’ and – besides firing warning shots at the Royal Navy and fighting off a coup attempt by German mercenaries – entered into a series of sketchy schemes to stay afloat. One enterprise, launched in 2000 with the help of cypherpunk Ryan Lackey, was for the Bates family to turn Sealand into the world’s first data haven: an unbreakable digital lockbox beyond the clutches of law enforcement agencies and copyright lawyers.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook, testifying before a joint hearing of the Senate Judiciary and Commerce committees, April 10 2018 (photograph by Douglas Christian/ZUMA Wire/Alamy Live News)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook, testifying before a joint hearing of the Senate Judiciary and Commerce committees, April 10 2018 (photograph by Douglas Christian/ZUMA Wire/Alamy Live News)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Joel Deane reviews 'An Ugly Truth: Inside Facebook’s battle for domination' by Sheera Frenkel and Cecilia Kang

- Book 1 Title: An Ugly Truth

- Book 1 Subtitle: Inside Facebook’s battle for domination

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette, $32.99 pb, 343 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/4erzOr

Sealand calls itself a micronation. No one else does. It’s easy to see why: the ‘kingdom’ is little more than a glorified helipad. It rises from the North Sea off the coast of Suffolk like a Greek version of the letter π rendered out of concrete and steel – the sole survivor of a series of Maunsell forts built to shoot down Nazi Kriegsmarine aircraft during World War II. Abandoned by Britain in the 1950s, the fort was hijacked by pirate radio broadcaster Paddy Roy Bates in the 1960s and renamed the Principality of Sealand. Bates crowned himself ‘prince regent’ and – besides firing warning shots at the Royal Navy and fighting off a coup attempt by German mercenaries – entered into a series of sketchy schemes to stay afloat. One enterprise, launched in 2000 with the help of cypherpunk Ryan Lackey, was for the Bates family to turn Sealand into the world’s first data haven: an unbreakable digital lockbox beyond the clutches of law enforcement agencies and copyright lawyers.

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)