- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The calculus of numbers

- Article Subtitle: The indefinite detention of EML019

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

After surviving two perilous boat journeys when he thought he would die, Jaivet Ealom is taken into the control of Australian authorities and given the designation EML019 on an identification card that manages to misspell his name. He will be referred as EML019 for the next three years, having arrived in Australian waters just five days after 19 July 2013, when a policy change meant that asylum seekers coming by boat would be transferred to the Manus Island or Nauru ‘regional processing centres’ to face indefinite detention and with no hope of resettlement in Australia.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Justine Poon reviews 'Escape from Manus: The untold true story' by Jaivet Ealom

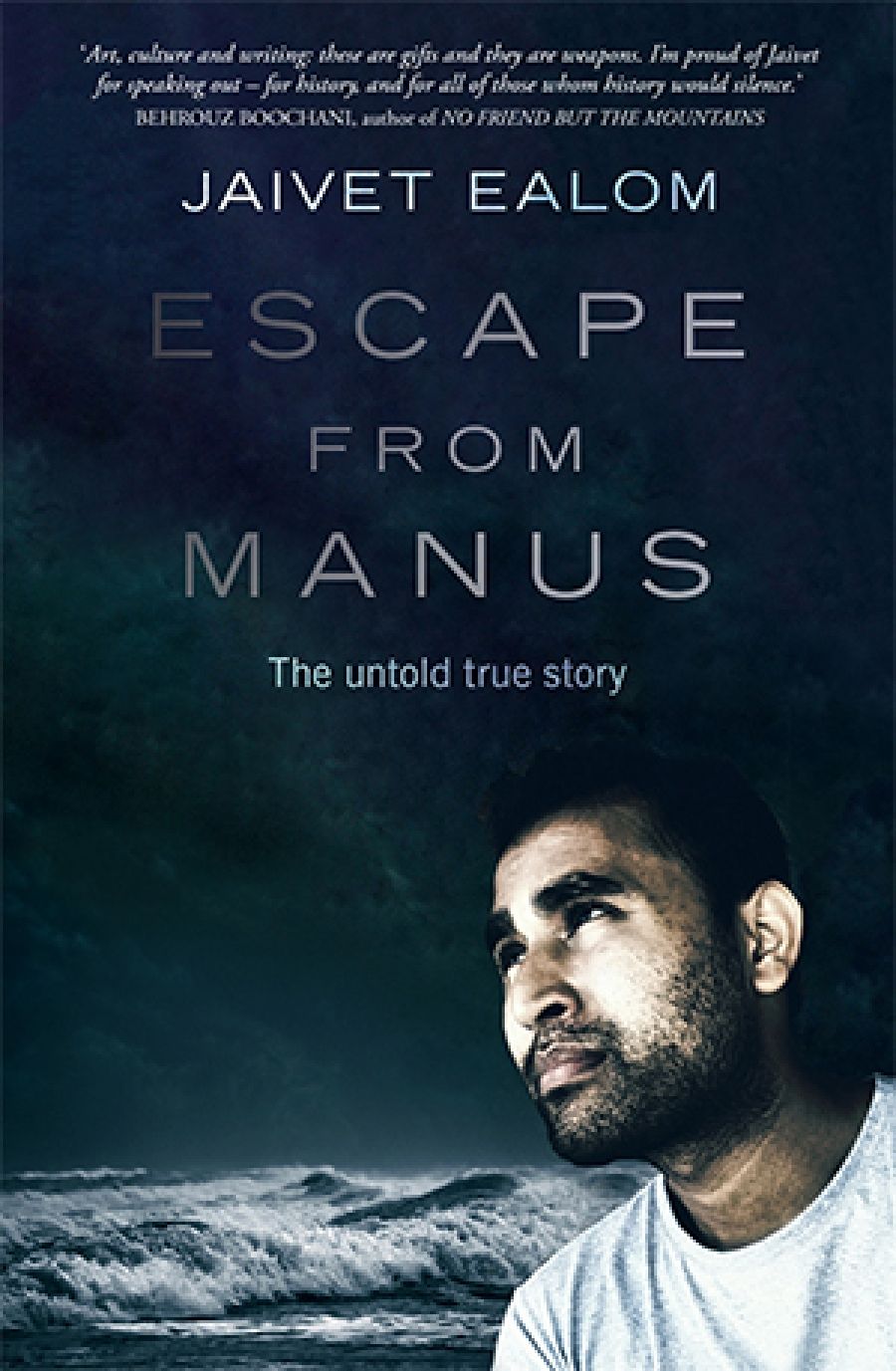

- Book 1 Title: Escape from Manus

- Book 1 Subtitle: The untold true story

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $34.99 pb, 347 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/rnzkOG

Escape from Manus recounts Jaivet Ealom’s story from his early life as a persecuted and stateless Rohingya Muslim in Myanmar to his odyssey through callous bureaucracies, indefinite detention, and violence. With careful planning, resourcefulness, and help from a few allies, Ealom finally reaches Canada and has his refugee status processed and recognised, giving him a chance to create a new life.

As a piece of personal storytelling, this book eschews the dehumanising legal language and media reporting that treated people Australia detained offshore as a homogenous mass identified only by six letters and numbers. Escape from Manus is also a page-turner in the prison-break thriller genre. The reader is taken on Ealom’s multiple daring escapes across Myanmar, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Fiji, and Hong Kong. The most significant escape – from Manus Island – gives the book its title and forms the bulk of the narrative.

At the Manus Regional Processing Centre, the physical harshness of state-run cruelty converges with the designation of a group of people as being unable to access a life in which their ambitions can bear fruit. According to Ealom, life in the detention centre was marked by arbitrary bans on phones and books, the heat of the metal shipping containers where the men slept, and lining up in the sun for hours to receive food ‘seasoned with stones and bits of gravel’. Overarching the daily humiliations is the sense of languishing through time made meaningless by the inescapable monotony of days in which nothing they did seemed to matter: ‘our futures were being systematically dismantled on the say-so of an Australian political party’.

Jaivet Ealom (photograph via Penguin)

Jaivet Ealom (photograph via Penguin)

Ealom’s account of interminable waiting is punctuated by moments of violence. The 2014 attack on the detention centre, led by some of the G4S staff who ran the security services and Manusian locals, resulted in the death of Iranian asylum seeker Reza Barati and left countless others with injuries. Ealom reflects on his initial bafflement at the hostility of the locals towards the detainees, who posed no threat to them: ‘the locals had been told we were hardened criminals … too dangerous to be controlled inside Australia.’ The book illustrates the ways in which high-level political decision-making circulates on the ground, manifesting as fear and enmity between groups of people who share the common condition of not having a choice about the existence of the detention centre and the presence of the refugees there: ‘Each of us, jailer or prisoner, was trapped in our own way in that abject place, with no purpose or direction, no past or future.’

It is this oscillation between Ealom’s experience and the larger political forces at play that gives the book its narrative power. The main cultural touchstones are, fittingly, Prison Break, the television drama that inspires Ealom’s real-life push for freedom, and Victor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning (1946), an account by a psychiatrist of his survival in the Nazi concentration camps, ‘with his body and spirit intact’. The quotes that head each chapter suggest a kinship with philosophers, histories of resistance and speaking truth to power, and the consolations of literature in providing explanatory power against violence. In the face of torments, the mind can still retreat and make plans.

Throughout his detention and escape, Ealom demonstrates an uncommon facility for observing detail and an actorly flair for inhabiting the affectations, language, and garb of those he needed to pretend to be at any one moment. We get the sense that tending to his inner life helped support him through the dehumanising treatment meted out at the detention centre. This young man ultimately frees himself from Australia’s grinding political machinery, at the cost of separating himself from family and the fellow detainees with whom he had formed strong bonds out of hardship.

Escape from Manus and Behrouz Boochani’s No Friend but the Mountains (2018) are stylistically very different, but both books open a crack in the government framing of who refugees are and what Australia is doing to them. The depiction of their humanity makes the reader pay attention; it counters the government narrative and the journalistic warp speed that drove media coverage. Both texts ask the reader to consider whether the detention of refugees is exceptional or a symptom of rot within a legal system that permits it.

J.M. Coetzee has asked, ‘does the calculus of numbers falter when it comes to matters of good and evil?’ The Australian government may plead that the law or humanitarian concerns demand offshore detention, but that does not remove its responsibility for what happens there. Whole territories may be excised as a legal trick, but the fact remains that the government is responsible for the treatment of the people whom it captures, transfers offshore, and detains. Jaivet Ealom exhibits courage in the face of the many pitiless systems that violated his rights and tried to take away his name. His act of writing reclaims his narrative.

Comments powered by CComment