- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

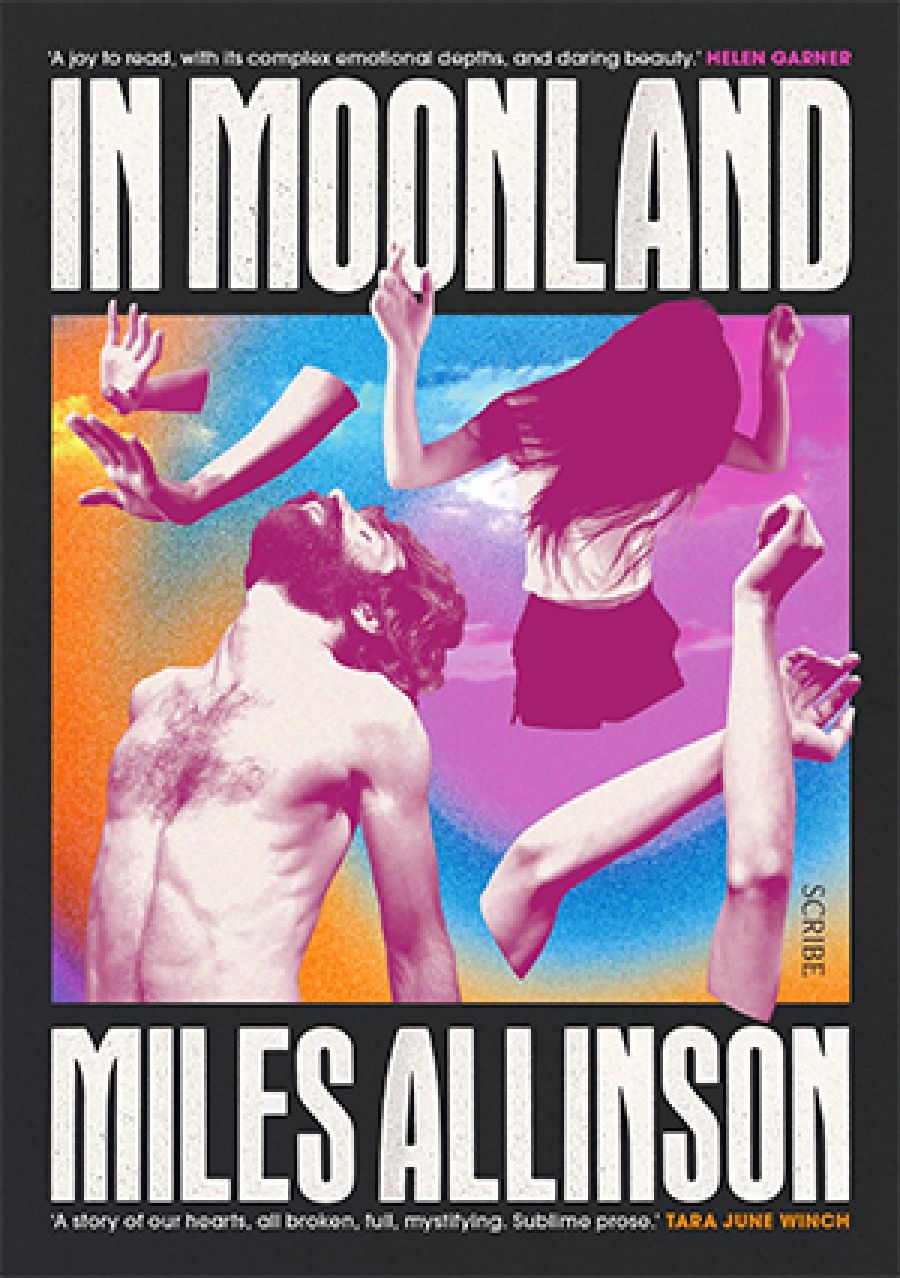

- Article Title: ‘Smoke in the head’

- Article Subtitle: Miles Allinson’s new novel

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In an ABC interview to promote his previous novel, Fever of Animals (2015), Miles Allinson shares a brief anecdote. When Allinson was aged sixteen or seventeen, a teacher told him that everyone turns conservative eventually. Allinson recalls his repulsion at the notion of this inevitable slide towards orthodoxy. His new novel, In Moonland, feels like a rebuttal. Joe, the narrator of the first part of the book, is caught somewhere between consent and revolt: though ambitious, he feels trapped by the flickering lights of his own computer, by the suburbs, and by his run-of-the-mill job. Orbiting him is a coterie of questions relating to his new status as a father, coupled with one more profoundly unanswerable question: why did his father, Vincent, kill himself? Only some of these questions are answered across a narrative that uses four different perspectives and three different timelines, from the present back to the 1970s and into the near future.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Daniel Juckes reviews 'In Moonland' by Miles Allinson

- Book 1 Title: In Moonland

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $29.99 pb, 256 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/7mGRer

Vincent gambled and was violent and angry. But, says Joe, ‘If you were to ask me what sort of father he had been, I would say that he was a good one ... and that he was a troubled person, with a loneliness that could not be cured.’ To Allinson’s credit, this kind of complex character populates the novel. Another complexity pulsing throughout is also first asserted by Joe: on becoming a father to Sylvie, he describes the terrible love a parent has for their child, alongside the more nonchalant love a child might have for their parent. But this nonchalance is belied by the single-mindedness of Joe’s search for Vincent, and his fear that something is missing from his family’s history.

Allinson describes with delicacy a hard truth of new parenthood: that the past is erased and that the future is exorcised too. ‘Is this how my own father felt when I was born?’ Joe asks. ‘As lost as this? ... Like his life had shrunk to the size of a blackened pea?’ This feeling of being lost and isolated increases alongside another of the novel’s central concerns: an endemic untetheredness that compels Joe backwards even as the pressure and tensions of family life bend him out of shape.

In Moonland unfolds cinematically and is, on occasion, overly visual. Perhaps this is due to the nature of memory or imagination in an over-heated, graphic age; certainly, it is a trope Allinson plays on, with myriad popular culture references as well as repeated nods to the tyranny and potential of screens. Some scenes, like those in which Joe dulls himself with YouTube and sinks into watching brutal, historical boxing matches, tread a fine balance: the prose remains beautiful, but also stark and harsh. Part of the burden of the book is revealed: that in the twentieth century banality has been pushed beyond what would normally have seemed commonplace. Even the moments that occur in the manic ashram where Vincent lived during the 1970s are dealt with perfunctorily, at a third-person distance. (This is the Shree Rajneesh Ashram, run by the many-named and deeply divisive Osho.) In the age of Netflix, with its addiction to cult-related content, these moments are the least interesting in the book. What is interesting are the reasons why Vincent was drawn to such a place, why Joe is drawn to Vincent, and why, in the end, some families work like lodestones.

Cinema pervades the novel in other ways. Joe visits the Screen and Television Archive in Melbourne to watch films made by his father’s friend, and describes the fragility of even these more official, archived steps into the past. Here, the narrative strains gladly at the flickering of a VCR, as the crew and actors of the film Joe is watching break to sit around a campfire and discuss what they might do next. At another moment, watching all the footage he can of the ashram, Joe describes the way ‘images pulsed like something that was alive’. At these closer, more active points in the novel, In Moonland ’s own intertextuality is cleverly signalled.

For Joe, screen time serves another function: to distort clock time. ‘Maybe films measure time – or dissolve it,’ he says. This dissolving is doubled when the film in question is poorly preserved, deliberately destroyed, or used to put a banner across reality. (In the closing section of the novel, set in the near future, Allinson filters things even further, through ‘skin suits’, ‘Vistas’, and ‘Xtended reality’.)

In this way, competition between reality and its proxies helps Allinson skewer both culture and counterculture. The commune and the cult are shown to be mostly futile in the face of what they resist, which is both the slipperiness of the present and the forces that shape it. If there is hope, it is faint, and it exists in smallness: in the ways in which family and memory offer meaning in the face of monomaniac mystics and neoliberal hellscapes.

In the novel, Osho declares that ‘the past is just smoke in the head. It is nothing.’ In Moonland works to disprove this statement: the past shouldn’t shape us, but does; it shouldn’t linger, but does, exhibiting itself in our bodies and in the various traces we manage to leave behind. The memories that mosaic the text go some way to demonstrate this; they work as explosions of connection and consciousness that feel authentic. This is strange, given the flimsiness of the past. But the result is the suggestion that Joe is not as alone as he thinks.

Comments powered by CComment