- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: What if?

- Article Subtitle: An adventure in counterfactuals

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

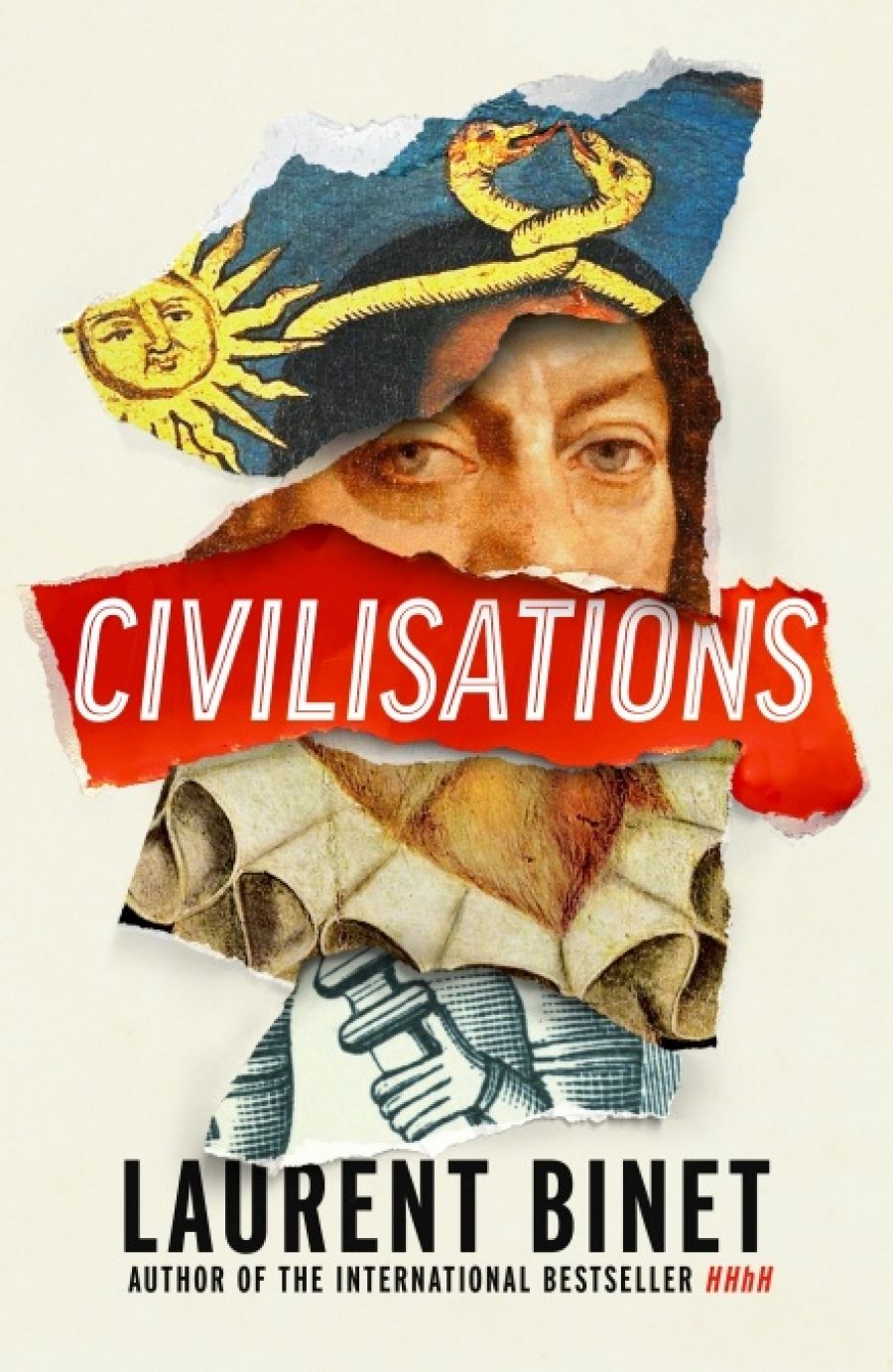

Acclaimed as the most original novel of the 2019 rentrée littéraire, and recipient of the Grand Prix du Roman de l’Académie Française, Laurent Binet’s most recent book, Civilisations (2019), is a cleverly crafted uchronia, or speculative fiction. The author is inviting us on an epic journey that devises alternative key moments in history, from a Viking tale to an Italian travel diary, and from the Inca chronicles to the capricious destiny of Cervantes. Let the adventure of counterfactuals begin …

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Cristina Savin reviews 'Civilisations' by Laurent Binet, translated by Sam Taylor

- Book 1 Title: Civilisations

- Book 1 Biblio: Harvill Secker, $32.99 pb, 310 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/e4ryvD

The year is 1000 CE. Erik the Red’s daughter, Freydis Eriksdottir, a red-haired, ferocious Viking woman, leaves Greenland on a ship to Vinland, in search of new territories. During her ambitious exploits, she encounters the Skraelings and befriends them by gifting them a pearl necklace and an iron brooch. The Greenlanders and the Skraelings exchange skills and knowledge: Freydis and her people teach the Skraelings to ‘extract iron from peat and to transform it into axes, lances and arrowheads’. In return, the Greenlanders learn to grow barley ‘by pushing the grains into little piles of earth, alongside beans and marrows’ and to build up stores for winter. By a cruel twist of fate, the Skraelings become almost extinct, for the Greenlanders also ‘gift’ them deadly diseases. Instead of returning to her homeland, Freydis, who has inherited her father’s wanderlust, sails south to Cuba, then Panama and finally reaches Cajamarca, where her ascent continues.

The year is 1492. A pious Christopher Columbus weighs anchor for the island of Cuba in search of gold, spices, and trade opportunities. His journal records wondrous stories of mountains, valleys, and beaches of unparalleled beauty. But the sailor from Genoa who crosses the ‘Ocean Sea’ to prove that the world was round never returns to his benefactors, Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon. He falls into the hands of the Inca. Despite the suffering, he remains true to his mission and to ‘the great Castile and its glorious, enlightened monarchs’.

The year is 1531. The Inca emperor Atahualpa departs Quito, passing through Cajamarca and Cuba, to begin his quest for the New World (Europe). His troops reach Lisbon at the time of the devastating earthquake, when the earth ‘had trembled and opened up and then an enormous wave had hit the coast’. They then proceed to Toledo, where the Spaniards and the Quitonians engage in battles of unspeakable cruelty. The Inca are unstoppable through Spain, Italy, France, Germany, and beyond. It is not just hard-fought wars and slaughter of the populace. Atahualpa is also a reformer; he understands that ‘it is more difficult to reign than to wage war’. Sterile lands in Europe are replete with new crops and canals, granaries are established to feed the hungry in times of need, and plots of land are given to peasants or to communities, while new tax reforms are put in place to reward ‘the merchants who funded the army with loans’. There is a celebration of life and compassion for the disabled, the elderly, and the infirm. As Atahualpa advances across the New World, languages, religions, traditions, and cultures meet, and new connections are formed. Titian, Tintoretto, and Cranach immortalise the power and glory of the emperor and his entourage. Atahualpa is introduced to money and quickly realises its importance in achieving his imperial dreams. Vinho, the black drink, becomes a favourite of his. The Inca Temples of the Sun emerge as new places of worship. But not everyone is willing to accept this new world order. An indignant Thomas More is awaiting death in the Tower of London, having refused to support the blasphemy of replacing monasteries and abbeys, throughout the kingdom of England, with Temples of the Sun. Atahualpa’s formidable reign reaches an epic finale in Seville.

The epilogue: a young Spaniard, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, flees his country and sets out on an adventure with his friend El Greco. Upon crossing the Ocean Sea, Cervantes reaches Cuba, a land full of marvels and abundant riches.

The structure of Civilisations, and Binet’s literary style, bring to mind a four-movement opus of varied tempos and motifs. The first two movements are short and sharp, the third by far the longest and most action-packed, while the finale is soulful and idyllic. Civilisations is a refreshing work that pushes the limits of historical fiction. The language is crisp and polished. There are shifts in style, most notably prompted by the insertion of epistles between Erasmus of Rotterdam and Thomas More, the intriguing Ninety-Five Theses of the Sun (a complete rewrite of Luther’s ninety-five theses?), poems in old Norse, and gentle strophes called ‘The Incades’. From time to time, the chronicles of Atahualpa are crowded with a plethora of names and events, making it somewhat challenging to keep up with the narrative; yet they contribute a successful crescendo to the overall tone of the book, which befits the story of the Inca emperor. Under the deft touch of Sam Taylor, the translator, we indulge, much like the Inca with the intoxicating vinho, in the novel’s langue exquise. Nowhere perhaps does the skill of the translator comes to the fore as much as in the graceful rendition of the verse (The Incades, Book I, Verse 20):

When Thor, the god who with a thought controls

The raging seas, and balances the poles,

From heav’n beheld, and will’d, in sov’reign state,

To fix the Eastern World’s depending fate,

Swift at his nod th’Olympian herald flies,

And calls th’immortal senate of the skies;

Where, from the sov’reign throne of earth and heav’n,

Th’immutable decrees of fate are given.

Finishing this ambitious saga of counterfactuals with a sense of exhilaration, we wonder if this innovative tale will pave the way for another uchronia.

Comments powered by CComment