- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Technology

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Dumb fucks’

- Article Subtitle: Facebook’s long record of denial and disdain

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Sealand calls itself a micronation. No one else does. It’s easy to see why: the ‘kingdom’ is little more than a glorified helipad. It rises from the North Sea off the coast of Suffolk like a Greek version of the letter π rendered out of concrete and steel – the sole survivor of a series of Maunsell forts built to shoot down Nazi Kriegsmarine aircraft during World War II. Abandoned by Britain in the 1950s, the fort was hijacked by pirate radio broadcaster Paddy Roy Bates in the 1960s and renamed the Principality of Sealand. Bates crowned himself ‘prince regent’ and – besides firing warning shots at the Royal Navy and fighting off a coup attempt by German mercenaries – entered into a series of sketchy schemes to stay afloat. One enterprise, launched in 2000 with the help of cypherpunk Ryan Lackey, was for the Bates family to turn Sealand into the world’s first data haven: an unbreakable digital lockbox beyond the clutches of law enforcement agencies and copyright lawyers.

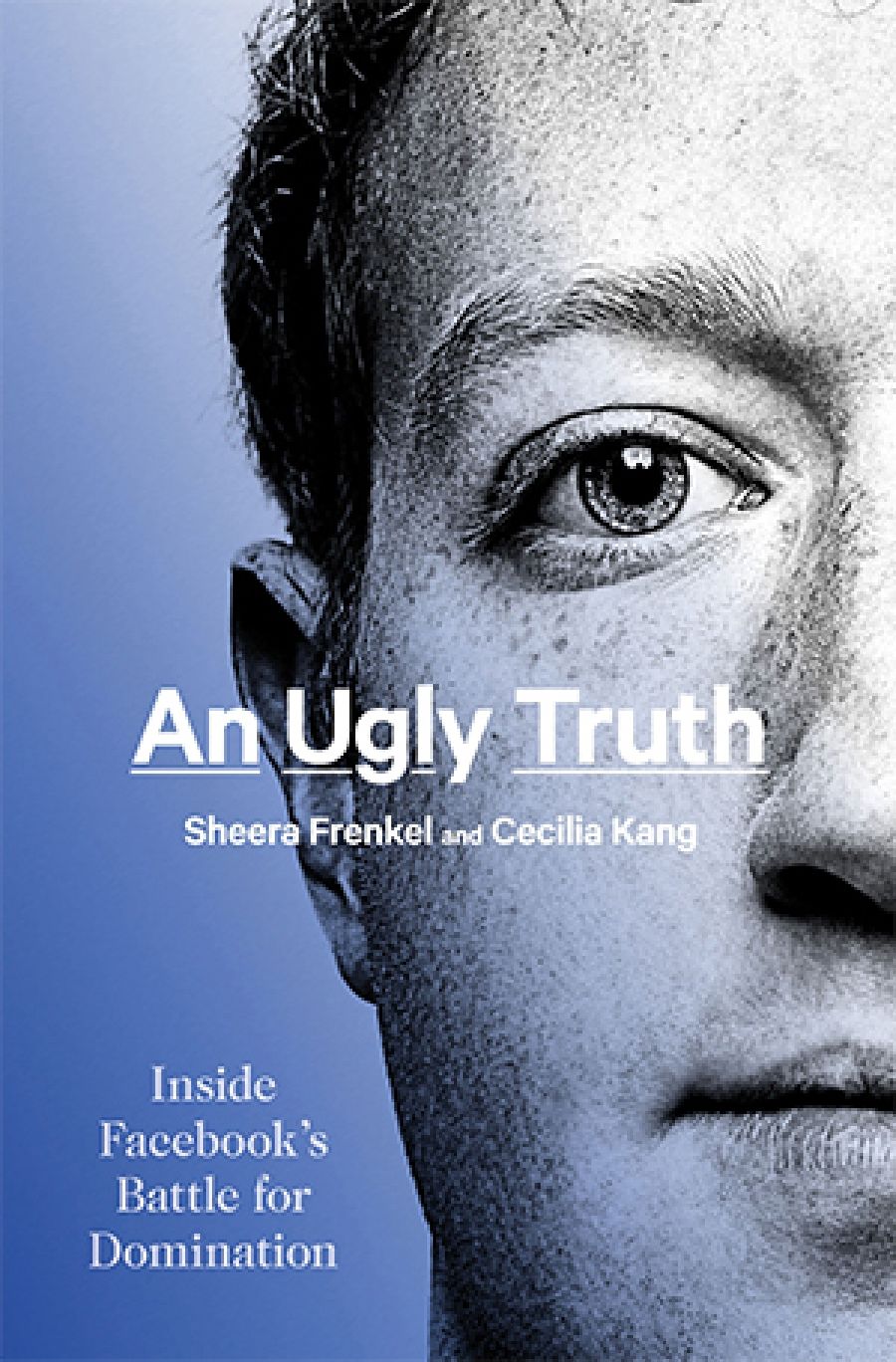

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook, testifying before a joint hearing of the Senate Judiciary and Commerce committees, April 10 2018 (photograph by Douglas Christian/ZUMA Wire/Alamy Live News)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook, testifying before a joint hearing of the Senate Judiciary and Commerce committees, April 10 2018 (photograph by Douglas Christian/ZUMA Wire/Alamy Live News)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Joel Deane reviews 'An Ugly Truth: Inside Facebook’s battle for domination' by Sheera Frenkel and Cecilia Kang

- Book 1 Title: An Ugly Truth

- Book 1 Subtitle: Inside Facebook’s battle for domination

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette, $32.99 pb, 343 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/4erzOr

To cut a long story short, the data haven promised more than it delivered. Perhaps that’s why the story of Sealand has always reminded me of the broken promise of the internet in general and Facebook in particular. After all, Sealand and Facebook are both pirate endeavours built on libertarian ambitions by founders with delusions of grandeur. The main difference is that Sealand’s Bates, who died in 2012, was harmless; Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg is not.

To appreciate the danger of Zuckerberg you have to understand the subculture he sprang from. Fundamentally, Zuckerberg sees himself as a computer hacker. Not the hackers you read about via the mainstream media – such as organised criminals holding computer systems hostage for Bitcoin, or battalions of geeks employed by spy agencies to steal industrial and national secrets – but the pure breed that arose in the United States in the 1960s. These hackers wanted to learn rather than steal. In their hippie-like quest for enlightenment, they tweaked, bent, and broke hardware, software, and networks, and they believed all information should be free.

In 2010, when Steven Levy was updating Hackers (1984), his cult book on hacking culture, he sought out Zuckerberg. At the time, Facebook was a relative minnow and Zuckerberg just twenty-six. Zuckerberg, born the same year that Hackers was published, allowed Levy to characterise Facebook as a company built on the hacker ethic. Levy, in turn, bought Zuckerberg’s line that Facebook was, like the original hackers, all about making information available to the people. In other words, Levy missed the point.

Facebook was never about hacking computers. It was always about hacking data; bending people instead of software. Its modus operandi is to hoover up as much digital information as possible about as many people as possible, algorithmically tweak that data to predict and shift human behaviour, and, in the process, make money.

Futurist Jaron Lanier has said that in Facebook’s business model ‘life is turned into a database’. At times, though, Facebook’s database has been more like an ATM than a data bank. For instance, between 2012 and 2014, Facebook’s Open Graph program allowed app developers to access the information of its users. That loophole delivered data harvested from three hundred million Facebook users to political consultants Cambridge Analytica via a third party. Cambridge Analytica used that data in a range of campaigns, including Brexit and Donald Trump’s first presidential bid. As Zuckerberg succinctly put it in a private discussion of the data he gathered from the first generation of Facebook users: ‘They “trust me”, dumb fucks.’

By any measure, Zuckerberg’s ‘dumb fucks’ hacking has succeeded. Facebook, which includes Instagram and WhatsApp, is one of only six companies in the world with a market capitalisation of more than US$1 trillion. It has 2.9 billion users, including sixteen million Australians, and is on track to earn more than $100 billion in revenue in 2021. Put it this way, if Facebook were a country, its gross domestic product would be larger than two-thirds of the members of the United Nations.

Maybe that’s why, in 2017, Zuckerberg said Facebook was ‘more like a government than a traditional company’ and posted a 5,700-word manifesto claiming that Facebook possessed the ‘social infrastructure’ to ‘make a global community that works for everyone’. Even by the standards of tech billionaires, who increasingly behave like feudal kings or villains from a James Bond movie, Zuckerberg’s it’s-a-small-world-after-all rhetoric was gobsmacking. His messianic promise to heal the world was also poorly timed, given that it was made a month after Trump was sworn in as president on the back of a campaign where WikiLeaks, Facebook, and the mainstream media were used as proxies by Russia to illegally undermine the candidacy of Hillary Clinton.

An Ugly Truth, a forensically reported book by New York Times journalists Sheera Frenkel and Cecilia Kang, goes a long way to explaining the global consequences of Facebook’s toxic combination of delusion, denial, and disdain.

Frenkel and Kang don’t fall into the trap of treating the rise of Zuckerberg like the origin story of a Marvel superhero. Instead, they focus on five years in the life of Facebook, starting with the 2016 US presidential elections and ending with the 2021 attack on Capitol Hill – the rise and fall of the Trump presidency. As a result, An Ugly Truth reads more like a study of power in the new gilded age than a puff profile of a tech company.

In this Moby-Dick of a tale, Trump is the orange whale, a leviathan frequently sighted, but never landed. Trump’s campaign first breached on Facebook in December 2015, when his campaign posted video of an inflammatory speech targeting Muslims. After some internal handwringing, Facebook tarted up a free-speech policy one insider called ‘bullshit’ and let Trump’s bigotry go viral. Trump never looked back. His campaign used Facebook’s vast database of hacked humanity to deliver targeted messages to voters and raise funds. Russia’s Internet Research Agency, meanwhile, complemented the Trump campaign’s efforts, using Facebook to deliver toxic anti-Clinton content to 126 million Americans.

Frenkel and Kang write that ‘Trump and the Russian hackers had separately come to the same conclusion: they could exploit Facebook’s algorithms.’ Call me cynical, but I doubt it’s a coincidence that Trump’s campaign and the Russians shared the same eureka moment about Facebook. As for Facebook, its security team first spotted the Russian interference in the US campaign in March 2016, eight months before Election Day, but failed to raise the alarm with authorities. Through inaction, therefore, Facebook helped Russia swing a US presidential election.

The reason why Facebook failed to act can be summed up in two words: Sheryl Sandberg. Before Trump, Sandberg was a darling of Davos jetsetters and wannabes – lauded as a feminist icon and leading businesswoman. After joining Facebook from Google, Sandberg was instrumental in turning Zuckerberg’s mountains of data into rivers of gold, creating an advertising business that tracked Facebook users almost everywhere they went online, then mined the data to push people towards products and services they didn’t know they wanted to buy. But, according to Frenkel and Kang, Sandberg was also instrumental in politicising Facebook’s content management.

Apparently, it all started with Tony Abbott.

In 2011, Facebook’s content managers refused to remove a page that attempted to attack the then Opposition Leader by vilifying his daughters. Abbott, understandably, was unimpressed. In response, Sandberg dealt directly with Abbott and started leaning into content management to avoid political fallout. From then on, a Facebook insider tells Frenkel and Kang, ‘it didn’t take a genius to know that the politicians and presidents who called [Sandberg] complaining about x or y decision would suddenly have a direct line into how those decisions were made’.

Sandberg also became Zuckerberg’s political firewall. She was the one sent to Washington to front congressional hearings and glad-hand politicians; she was the one who hired a small army of lobbyists to fête Trump; she was the one responsible for the security team that discovered Russian meddling in the 2016 campaign; and, when Facebook came under fire for appeasing Trump, she was the one who took the heat.

Zuckerberg came under political fire, too, as Frenkel and Kang record, but Sandberg was the one with the most to lose. Unlike the impregnable Zuckerberg, who holds majority stock control over Facebook, Sandberg – seen internally as arrogant and externally as self-serving – is dispensable and appears to have lost ground. Despite a decade of promises, she has done little to make Facebook’s staff more diverse, with just thirty per cent of leaders female and only four per cent of employees Black by the end of 2018. Facebook increasingly rolls out former British politician Nick Clegg (its Vice President of Global Affairs) instead of Sandberg for media duties.

Reading between the lines, Zuckerberg, who first met Sandberg when he was twenty-three, outgrew his need for her once he started dealing directly with politicians such as Trump. In that light, Zuckerberg’s 2017 manifesto can seem like a milestone if you squint and ignore the hubris. Only time will tell whether Zuckerberg’s promise to usher in a kinder, gentler global community is cover for another round of data hacking in the pursuit of profit and power.

This much is certain. Zuckerberg – who is fond of quoting Al Pacino’s Michael Corleone and Brad Pitt’s Achilles and is a fan of the Roman Emperor Augustus – is behaving like the prince regent of his virtual kingdom. For instance, Zuckerberg has installed an independent committee to have the final say on content management – calling them Facebook’s ‘Supreme Court’ – and plans to launch a digital currency pegged to the US dollar.

All in all, it’s pseudo-sovereignty beyond the wildest dreams of Paddy Roy Bates, but don’t feel too bad for Sealand. They get by selling passports, titles, and souvenirs on the internet. They even have a page on Facebook.

Comments powered by CComment