- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘A creepy little walk’

- Article Subtitle: Toby Fitch’s lyricism and versatility

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Sydney-based poet and editor Toby Fitch has spent much of the last decade traversing the field of radical French modernist poets, especially Arthur Rimbaud and Guillaume Apollinaire. That engagement ignited Fitch’s imagination. He began inverting, recombining, mistranslating, and mimicking their techniques in his own poetry. In his new collection, Sydney Spleen, he has made a sophisticated, fresh move that enhances his signature playfulness and tongue-in-cheek poetic antics.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Pam Brown reviews 'Sydney Spleen' by Toby Fitch

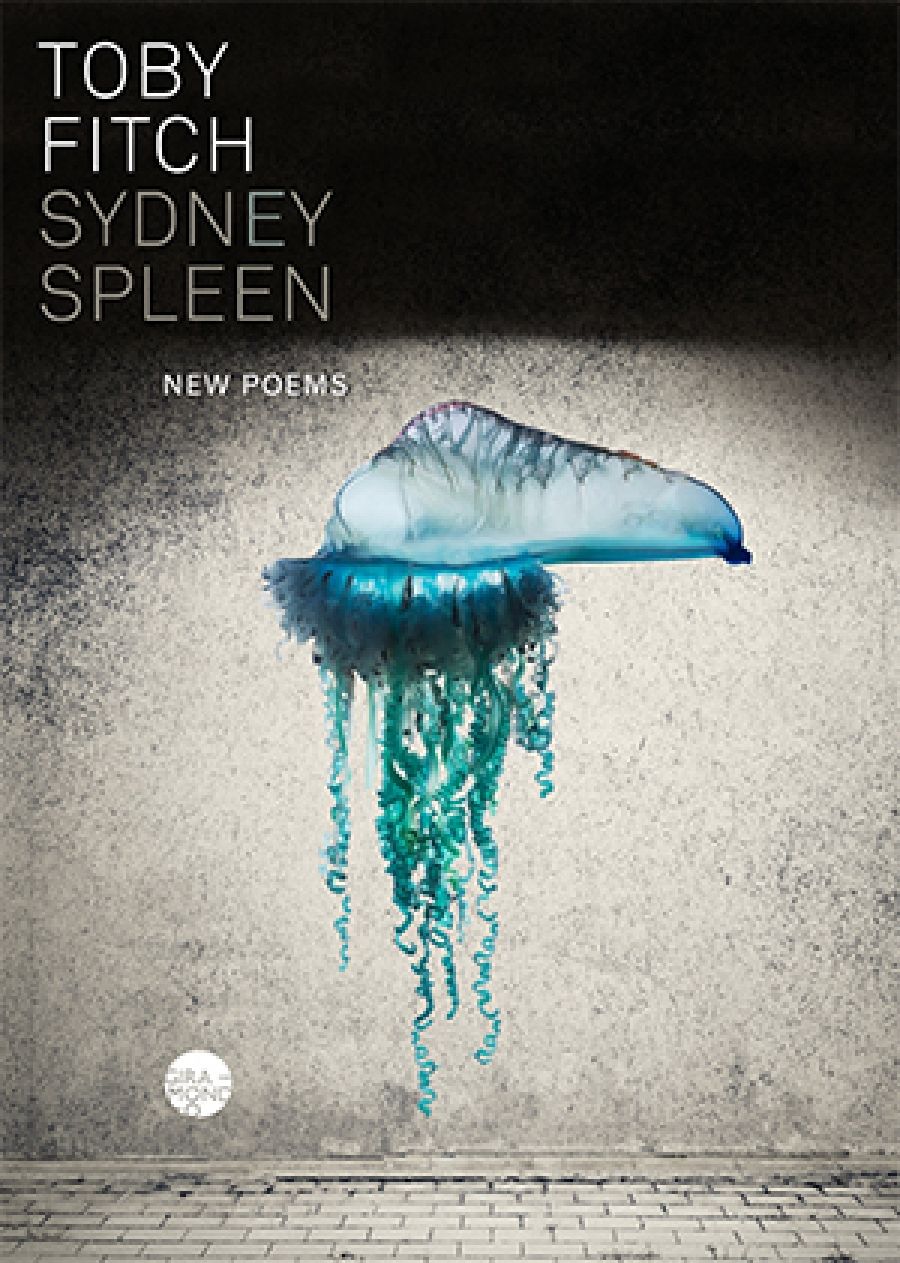

- Book 1 Title: Sydney Spleen

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo, $24 pb, 103 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/XxL02M

Over the past few years, the poems have accrued gradually in a desktop folder. In 2020, the beginning of the present-day pandemic was an event which, Fitch says in an author note:

unearthed all kinds of splenetic moods, and so in lockdown ... I found myself writing into the nights to capture the fragmented emotions I was experiencing with my family ... as we watched and re-watched a world seemingly undergoing apocalypse upon apocalypse – megafires, 1 billion animals dying, massive hailstorms and flooding, the ongoing pandemic, the return of fascism ‘like a fossilized piece of moon’ (Ernst Bloch); all symptoms of a broken but still all-consuming capitalist system that allows the ruling classes to exploit the Earth unchecked at the expense of minorities and the working class.

That final pronouncement immediately corresponds with Baudelaire’s fiercely provocative piece ‘Assommons les pauvres! ’ (‘Let’s Beat Up the Poor!’), written in an attempt to materialise class struggle.

Sydney Spleen begins beautifully miserably with ‘Spleen 1’ – ‘January, pissed off with Sydney, pours / steaming torrents on the lessees / of Camperdown cemetery and mortal dumps / on the tenants and landlords of suburbia’.

Though contemporary Sydney is hardly mid-nineteenth century Paris, Fitch – like the most prominent flâneur, the anonymous loiterer Baudelaire – goes out on walks around the city. The cool sarcasm of ‘New Phantasmagorics’ starts: ‘Went for a creepy little walk. Navigating / a global pandemic, we go nowhere. / The future is shiny but who keeps it shiny. / The sun’s not a sphere, it’s a runnel / you get stuck in when you stare straight into it. / My eyes are barcodes ...’

Fitch rarely writes ‘An Absolutely Ordinary Poem’. Here he can’t resist the pleasures of merging influences. The poem is anything but ordinary. It riffs on Les Murray’s 1969 poem ‘An Absolutely Ordinary Rainbow’, where a man’s relentless weeping in Martin Place brings the hectic city to a standstill. When the man stops crying, ‘he simply walks’ through the crowd, post-epiphany, and hurries off. In John Forbes’s ‘On the Beach: A Bicentennial Poem’ (1988), trade unionists watch a man behead a chicken in Martin Place and, ‘not being religious’, they ‘bet on how many circles / the headless chook will complete’. To me, Fitch’s mash-up ironises old schisms. In the 1980s, Murray, ‘bard of the bush’, expressed hostility to ‘inner-city élites’ and postmodernists like Forbes, who once remarked, countering Murray, that his generation wrote about mining corporations’ destruction of the bush, not romantic nature poems. North American Mary Ruefles’s poem ‘A Certain Swirl’ provides the idea for Fitch: ‘The classroom was dark, all the desks were empty, / and the sentence on the board was frightened to / find itself alone.’ Fitch begins: ‘Martin Place was dark, all the cafes were empty, / an office above flickered with fluoro light / and the poem on the pavement was petrified / to find itself alone ...’ Like Ruefles’s sentence, the poem, even though ‘perhaps it was a shit poem’, remained unread.

Fitch has worked for several years as a sessional academic for various universities. Scandalously, university casuals were not granted financial support when classes were cancelled due to the pandemic. The university, which for years had relied on casual labour, deserted them. In Sydney, with union support, the casuals negotiated their dire situation with administrators and departmental academics to no avail. The union took the university to the Fair Work Commission on Fitch’s behalf and won the case. During the months of protest and uncertainty, Fitch wrote impassioned poems ridiculing administrative behaviour. ‘A Massage from the Vice-Chancellor’ lampoons risible and condescending managerial jargon. The book’s other political poems express a general discontent with current Australian politicians. The scathing poem ‘Left Hanging at the End of the End of the World Campaign’ rails bitterly against the lack of government action on climate change.

Sydney has been nicknamed ‘Tinsel Town’. More refined, David Williamson, a satirical playwright from Melbourne, called it ‘Emerald City’. Fitch looks ‘Beneath the Sparkle’, going underground on a tour of the tunnels on both shores of the harbour. Not quite the Parisian Catacombs but, ‘unused for the wetter part of the century’, the damp atmospherics do lead to an abandoned nineteenth-century cemetery below Central Station’s Platforms 26 and 27. Fitch makes a mockery of a politician’s plan to sell the city tunnels off for subterranean entertainments and eateries – ‘a fresh kind of colony in the underworld is being floated by the minister’.

‘Morning Walks in a Time of Plague’, the final poem, displays yet another slant – more sanguine in its remarkable familial intimacy, humour and discerning reflection. The alluring versatility and lyrical expansion in Toby Fitch’s new poems offer the reader many intricate intensities and illuminating pleasures.

Comments powered by CComment