- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Airwave feminism

- Article Subtitle: A history of women broadcasters

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the era of perpetual Covid lockdowns, many of us can relate to the isolation of the mid-twentieth-century housewife. Like her, we’re stuck at home, orbiting our kitchens, watching the light move across the floorboards. Each day mirrors the last, a quiet existence spent mostly in the company of the immediate household. Yet whereas we can flee our domestic confines via Netflix or TikTok, last century’s housewife had fewer avenues to the wider world. There was reading, of course – books or magazines or newspapers – but this was usually reserved for the end of the day. For most waking hours, her hands and eyes were needed for cooking, cleaning, mending, childcare, and a thousand other tasks.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

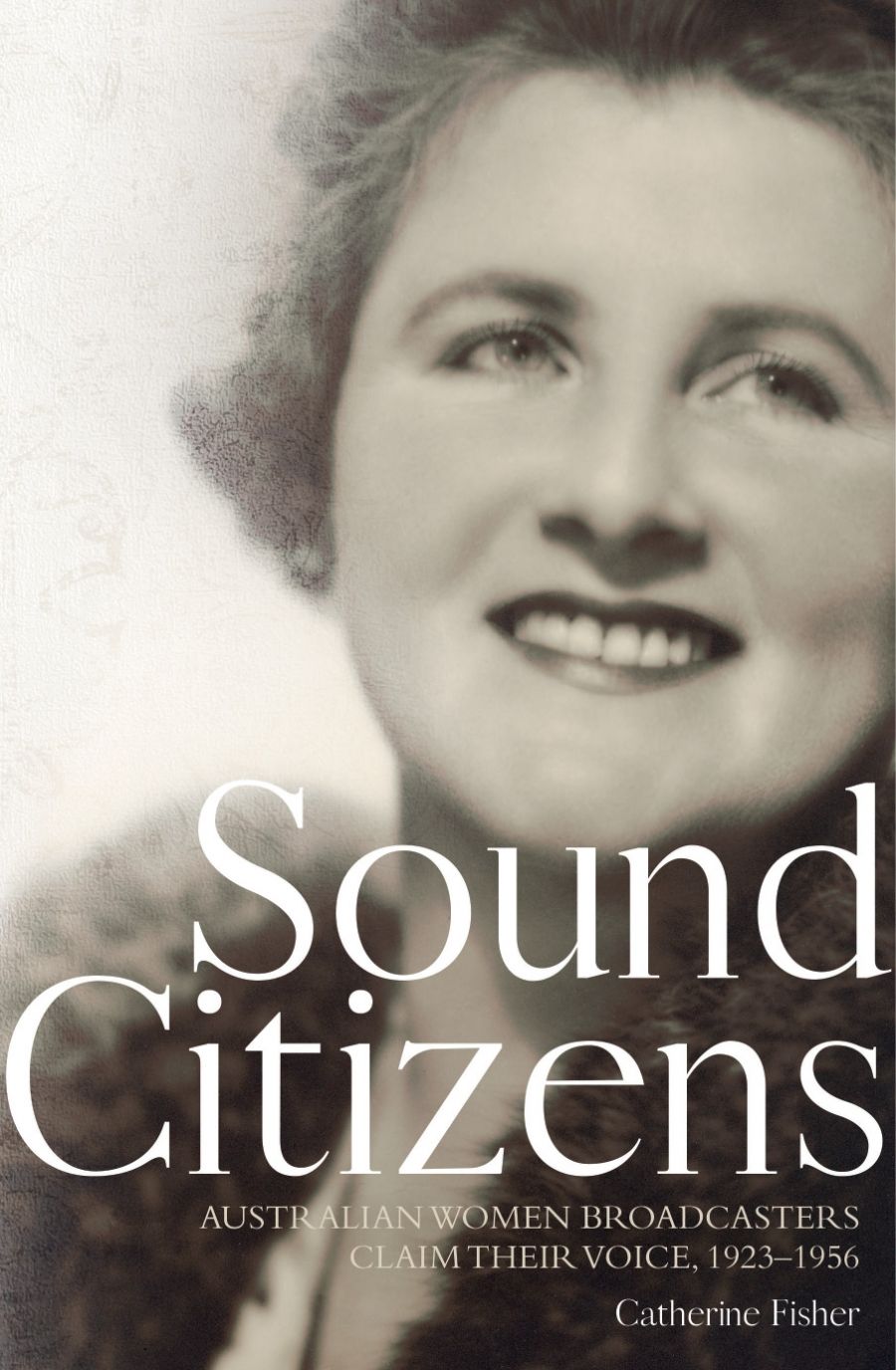

- Article Hero Image Caption: A portrait photograph of Enid Lyons, a politician and broadcaster, taken in the 1940s (History and Art Collection/Alamy)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): A portrait photograph of Enid Lyons, a politician and broadcaster, taken in the 1940s (History and Art Collection/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Yves Rees reviews 'Sound Citizens: Australian women broadcasters claim their voice, 1923-1956' by Catherine Fisher

- Book 1 Title: Sound Citizens

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australian women broadcasters claim their voice, 1923-1956

- Book 1 Biblio: Australian National University Press, $50 pb, 194 pp

Enter radio: the perfect accompaniment to the domestic grind. From 1923, when radio arrived in Australia, until 1956, when television appeared on the scene, radio was the unrivalled queen of daily household entertainment. For women who didn’t work outside the home (the majority), radio was friend, companion, entertainment, education, and, above all, a portal to the outside world. It injected the public sphere into the domestic, turning wives and mothers into engaged citizens. It broke down the isolation of individual women and fostered female community and solidarity. In short, the wireless was a vehicle of women’s advancement.

The feminist potential of radio was well recognised by women at the time. As Enid Lyons reflected in 1954, radio ‘created a bigger revolution in the life of a woman than anything that has happened any time’. A politician and broadcaster, Lyons was part of a cohort of radio women who shaped this revolution from behind the microphone. Alongside the likes of feminist Jessie Street, internationalist Constance Duncan, and ABC Women’s Session host Ida Elizabeth Jenkins, Lyons was one of many white women activists and broadcasters who used radio to make their mark in the public sphere and edify their largely female audiences.

These radio women are the focus of Catherine Fisher’s début monograph Sound Citizens: Australian women broadcasters claim their voice, 1923–1956. Developed from Fisher’s PhD thesis, Sound Citizens is an eye-opening history that details the myriad ways women broadcasters engaged with radio, across both the ABC and commercial stations.

The examples are legion. During the Great Depression, radio clubs such as the 2GB Happiness Club founded by Eunice Stelzer provided solidarity and mutual aid. As war clouds gathered in Europe, pacifists like Ruby Rich used radio to call upon women to demand peace. Later, in the 1940s, the first cohort of elected female politicians, including Lyons and Senator Dorothy Tangney, deployed radio as a campaign tool to further their political careers. In the 1950s, women’s show hosts Irene Greenwood and Catherine King crafted highbrow (and in Greenwood’s case, explicitly feminist) programs that brought art, politics, and ideas into the home.

Importantly, this broadcasting normalised women’s voices in the public sphere. At a time when public life was almost exclusively a male domain, radio became a rare space where women spoke with authority to a vast audience. As Fisher writes, ‘radio provided a platform for Australian women to speak and be heard in public on a scale not previously experienced’. As such, women’s broadcasting can be regarded as an inherently feminist act, no matter the content, as the mere fact of a having a woman behind the microphone challenged the norm of female deference to male speech. Radio helped women ‘claim their voices as citizens’, Fisher declares.

Fisher is not the first to make this argument. Sound Citizens sits within a growing body of revisionist scholarship that debunks earlier assumptions that women had scant presence on the airwaves. Both within Australia and around the world, the long-held truism was that radio reflected and reinforced existing gender norms. Male announcers were presumed to be the norm, with women allowed on air only to dispense recipes on lightweight women’s shows that trained listeners to be good housewives. In recent decades, this idea has come under scrutiny from a growing wave of feminist historians. In the United States, Britain, and Europe, there has been a deluge of scholarship testifying that women were in fact heard on radio in sizeable numbers and regularly tackled topics far meatier than the Sunday roast. This female presence extended to the early BBC, as British historian Kate Murphy shows in her book Behind the Wireless (2016). From the early 2010s, interest in the neglected history of women’s broadcasting also took off in Australia, with pioneering research conducted by Jeannine Baker, Kylie Andrews, and Justine Lloyd.

Fisher is part of this new wave, and her monograph is the first full-length Australian history on the topic. Despite the perennial challenges of radio history (little audio survives, leaving historians to stumble along with textual sources such as radio magazines), Fisher’s meticulous research eradicates any doubt that radio benefited women as both listeners and broadcasters. This was true of the ABC and commercial stations; however, the latter were often better vehicles for feminist messaging as they lacked the script vetting and managerial oversight that hamstrung announcers on the national broadcaster.

The chapter on rural broadcasting is a particular highlight, with Fisher tracing how radio women in areas such as the Riverina and Western Australia’s wheatbelt fostered distinctive regional identities and mitigated the isolation of farming life. Indeed, Western Australia emerges as the national star of women’s broadcasting, home to legends such as Irene Greenwood and Catherine King – a striking fact that merits further analysis. The inimitable Greenwood, whose lengthy radio career culminated in her own show, Woman to Woman (1948–54) on Perth station 6PM, surely deserves a dedicated biography.

Beyond the specifics of radio, Sound Citizens can also be read as a pre-history of the nexus between feminism and technology so familiar to us today. For as Fisher makes plain in the conclusion, the social-media fuelled #MeToo campaign was not the first time that feminists mobilised cutting-edge media, but rather one moment in a long history of feminist technology in which radio once played a critical role. Before Twitter and hashtags, the wireless was the megaphone of choice to reach the masses. Although we persist in imagining science and computing as male, feminists have always used the latest tech to speak and be heard.

Yet progress remains frustratingly slow. As any glimpse of Twitter will confirm, even a full century on from the origins of Australian women’s radio speech, we still struggle to accept a woman with things to say in public. We may have moved from radio waves to internet cables, but some things remain little changed.

Comments powered by CComment