- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Exiles and wanderers

- Article Subtitle: Two poets’ lateral moves

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Chinese poet is so often a wanderer and an exile. The tradition goes back to Qu Yuan (c.340–278 BCE), author of ‘Encountering Sorrow’, the honest official who was banished from court and drowned himself in a river, and it continues to our time. During the Sino–Japanese war (1937–45) a group of patriotic early Chinese modernists were displaced from their Beijing universities to an improvised campus in the south-west, where they read avant-garde Western poetry.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Nicholas Jose reviews 'The Gleaner Song: Selected poems' by Song Lin, translated by Dong Li and 'Vociferate | 詠' by Emily Sun

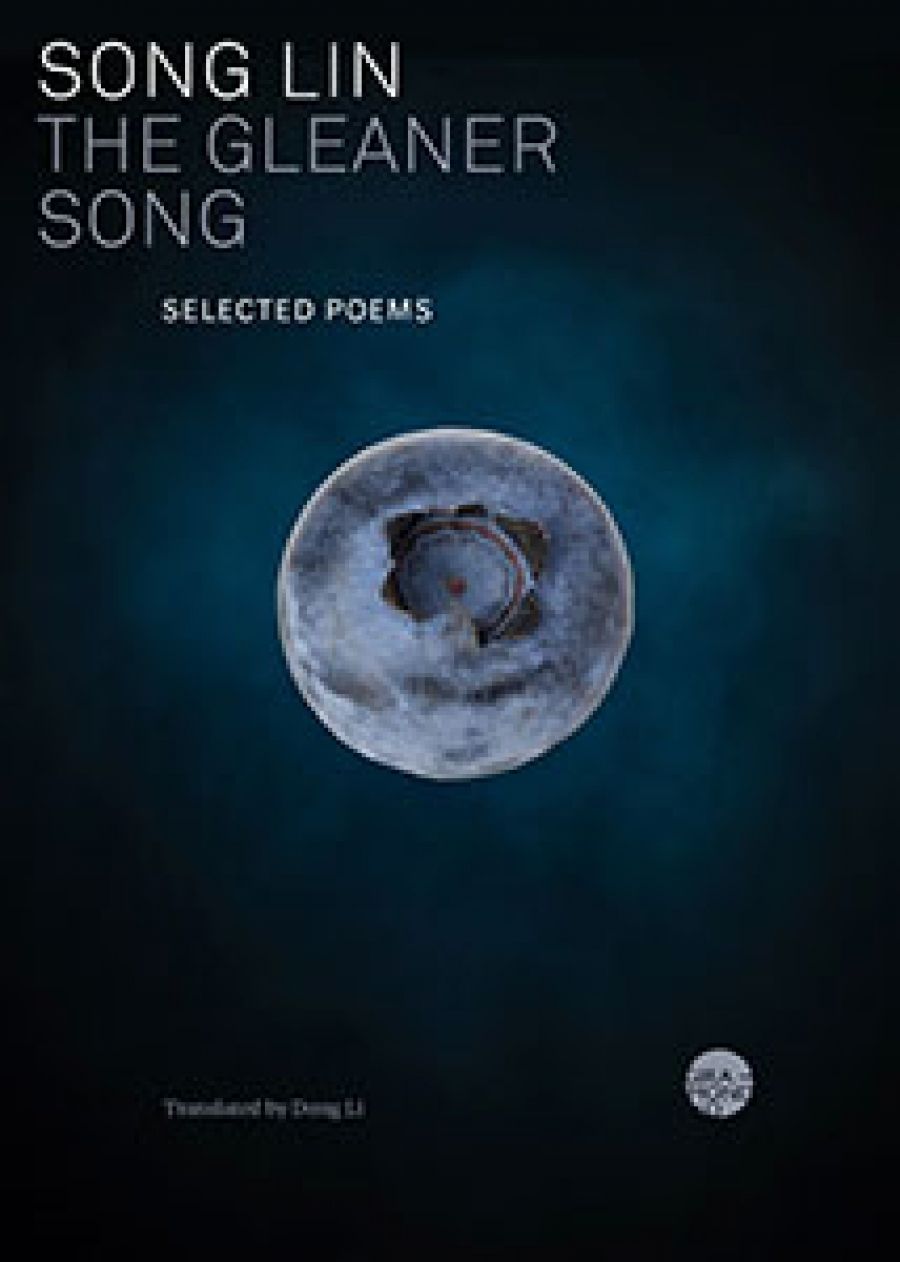

- Book 1 Title: The Gleaner Song

- Book 1 Subtitle: Selected poems

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo, $24 pb, 76 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/2rQbXM

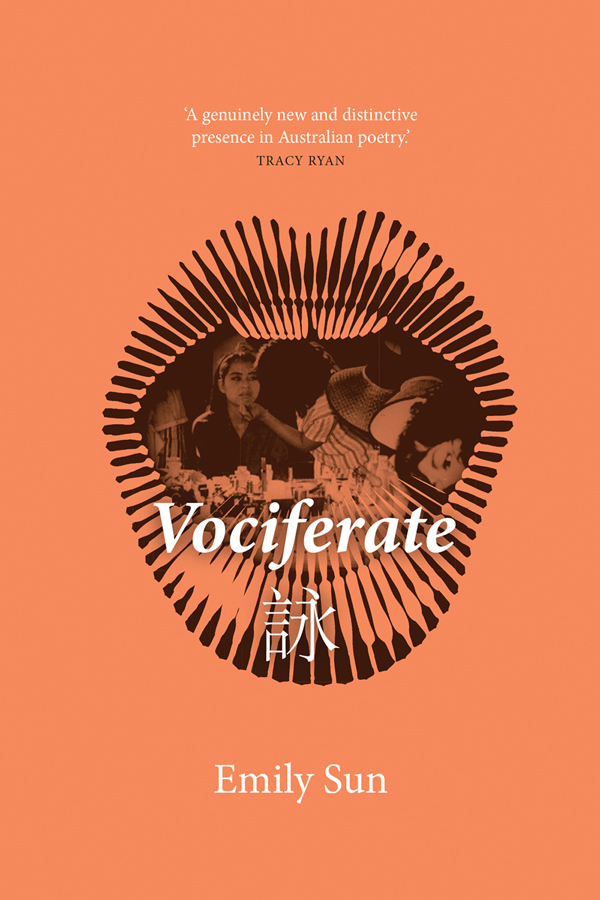

- Book 2 Title: Vociferate | 詠

- Book 2 Biblio: Fremantle Press, $29.99 pb, 110 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/1_SocialMedia/2021/May_2021/Vociferate.jpg

- Book 2 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/4erORL

The panoramic poem ‘Providence and Poetry’ considers the cost, back to Homer and Qu Yuan, who ‘floated on the water’, and forward to Song’s own contemporaries:

In all nations on this planet earth exile

Runs through the history of mankind, and that of the suffering poets

Occupies a significant chapter.

The poem names Lin Zhao (1932–68), the poet martyr who wrote with her own blood from prison in Shanghai before she was shot for crimes against the state. It names Haizi (1964–89), who threw himself under a train, ‘sliced through’ by ‘the mysterious number of 1989’. Others cited include Paul Celan (1920–70), whose suicide in the Seine is emblematic of ‘divine punishment’ for seeking meaning in deathly times: ‘he drinks away the root of the last word’. The river is a recurrent metaphor for Song. It flows into the large ocean that is poetry, as if, for all the grievous weight of history and politics, language – floating, drifting, ‘the suitcase [that] is your canoe’ – might be buoyant enough to survive.

The language crosses to readers of English, thanks indistinguishably to the translator, the poet Dong Li, also from the PRC, younger again, another migrant who now writes in English. His collaboration with Song Lin is the result of a Translation Lab residency at Ledig House in upstate New York. ‘[Song] is a curious poet who opens himself to the world around him,’ writes the translator. ‘His songs migrate … from one language to another … [in] a sensitive anthropology of our migratory world.’ Absorbing Western influences into the fabric of Chinese literary tradition, Song’s poetry is ‘a rotating brocade’ of gleanings. The translator’s job is to find an accommodating habitat in English. The last poem in the book, inspired by a walk in the countryside and dedicated by the poet to the translator, is a brilliant example. The Chinese poet who comes ‘with the cunning and curiosity of an oriental man’ turns into an American poet ‘just walking a little further / to stretch the distance from the old I’. This relaxed poem supports literary scholar Leo Ou-fan Lee’s suggestion of ‘translation’s highest and truest aspiration: friendship’.

What happens when we read Chinese poetry in English? A space for interpretation is needed if the poetry is to continue to travel. There is lively debate among practitioners and theorists of literary translation in relation to contemporary Chinese poetry. I like Nick Admussen’s invocation of French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy’s concept of ‘being-in-common’ as a reflection on the creative sequence that can open up, especially in multilingual performance:

The community built between the original text and the translation, between artists, translators, and audiences, exists in a social, political, and historical moment … The being-in-common between translated and original texts provokes and reflects a being-in-common between artist and translator; those commonalities … then connect local and foreign audiences.

In this spirit, The Gleaner Song reaches across distance in a tender appeal to readers to join in the relation that Song Lin and Dong Li offer – elegant, melancholy, passing on borrowed glories gathered on the road.

Perth-based poet Emily Sun uses the word ‘translanguaging’ to acknowledge an aspect of her creative process in the début collection Vociferate | 詠. The result is a complex personal rhetoric unafraid to push past boundaries when necessary. Words in Cantonese and Mandarin script break through, transliterated and translated at the bottom of the page. There’s French and Latin too, and everywhere a sense of the malleability of the ‘bastardised language’ that is English. The author’s biographical note alludes to the poems’ grounding in life experience. Sun was born in Hong Kong, moved to England at three, migrated to Australia at eight, and later travelled the world, including to Beijing. The language shifts involved in that journey register challenges of identity and meaning: ‘must I belong? can I belong with /so many incongruencies?’ Sun’s poetry finds points of stillness, but cannot stay still for long. It is spiky, probing, unexpected in its lateral moves.

‘Origins’ begins: ‘let’s see how we want our story to unfold … flows of stories … drifting’. ‘Perspective?’ is the question. Yet this opening poem ends with finality: ‘there has always been loss’. As in poems such as ‘Heavenly Piece’ and ‘We Need to Talk About Immigration …’, lines press to both edges of the page as if demanding a way out. Sometimes the ‘back and forth’ resolves itself in an unarguable punctum. ‘Noblesse Oblige’, for example, a poem about Hong Kong’s beginnings in colonial rape – ‘a city (my home) born of violence’ – reduces to:

tearing. membranes.

memories.

meaning.

The amusing ‘Palatable’, about the limitations of a right-thinking Australian, ends bluntly: ‘easy tropes’. Sometimes the point is a double meaning (‘national front’, ‘one nation’) or puzzle, as in ‘Six Two Six’, a rendering of Mozart’s Requiem as raging black comedy end-of-life hospital experience that lands on this centred couplet: ‘music ceases / to explain.’ The poet knows how to deliver a full stop.

What’s in a name? The Chinese half of the book’s double title Vociferate | 詠 is the opposite of vociferous shouting. 詠, yǒng in pinyin, is an old character meaning to chant or sing. It is also the author’s given name. But, as the poem ‘Romeo Would, Were He Not Romeo Call’d’ reveals, it proved ‘too difficult’ and was ‘traded for Wuthering Heights’, that is, for Emily Brontë’s Christian name. From the name change on, Emily Sun oscillates between languages, homelands, sameness and difference. She’s the ‘Wandering Minstrel in Translation’ in one of my favourite poems, ‘a mashup of my own translations of misheard Chinese song lyrics’: ‘colour struggle, life’s sacrifice / loss of possession / yet there is still hope’.

This is Australian poetry, too, with suburban settings providing material for many of the scenarios, though Australia can never simply be home. Place is layered and unstable, as fractured as the language that speaks it. Nothing can be taken for granted:

I am happy to stay in this time

Lie on this dried grass

patched over dunes

breathe clean air

(with your permission of course)

until the ocean reclaims the shore.(‘Property Rights’)

The book concludes with a poem called ‘Tribal Affiliations’, which returns to the question of origin underlined in the opening dedication: ‘for my mother / & / my two grandmothers’. The maternal line returns to motherland and mother tongue like an umbilical cord. What will happen to those affiliations now? ‘Where? / Which country? / … there is no reply …’ As a Chinese woman in Australia, the speaker, we guess, is determined to ‘unbound’ herself: ‘no one likes an angry woman’. Except her readers.

Comments powered by CComment