- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘My childbearing hips’

- Article Subtitle: An emotionally powerful anthology

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On her explosive, feminist début album Dry (1992), a young P.J. Harvey sang ‘Look at these my childbearing hips’, proudly proclaiming women’s strength and physicality. The word ‘childbearing’ conjures strong feelings and images for many of us – whether of childbirth, sleep deprivation, devotion, or a whole new way of life. It signifies much more than childbirth itself and is a fitting choice for the subtitle of this anthology, Poetry on childbearing. This emotionally powerful collection covers an expansive range of experiences: infertility, conception, pregnancy, birth, and life with a baby (or not).

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

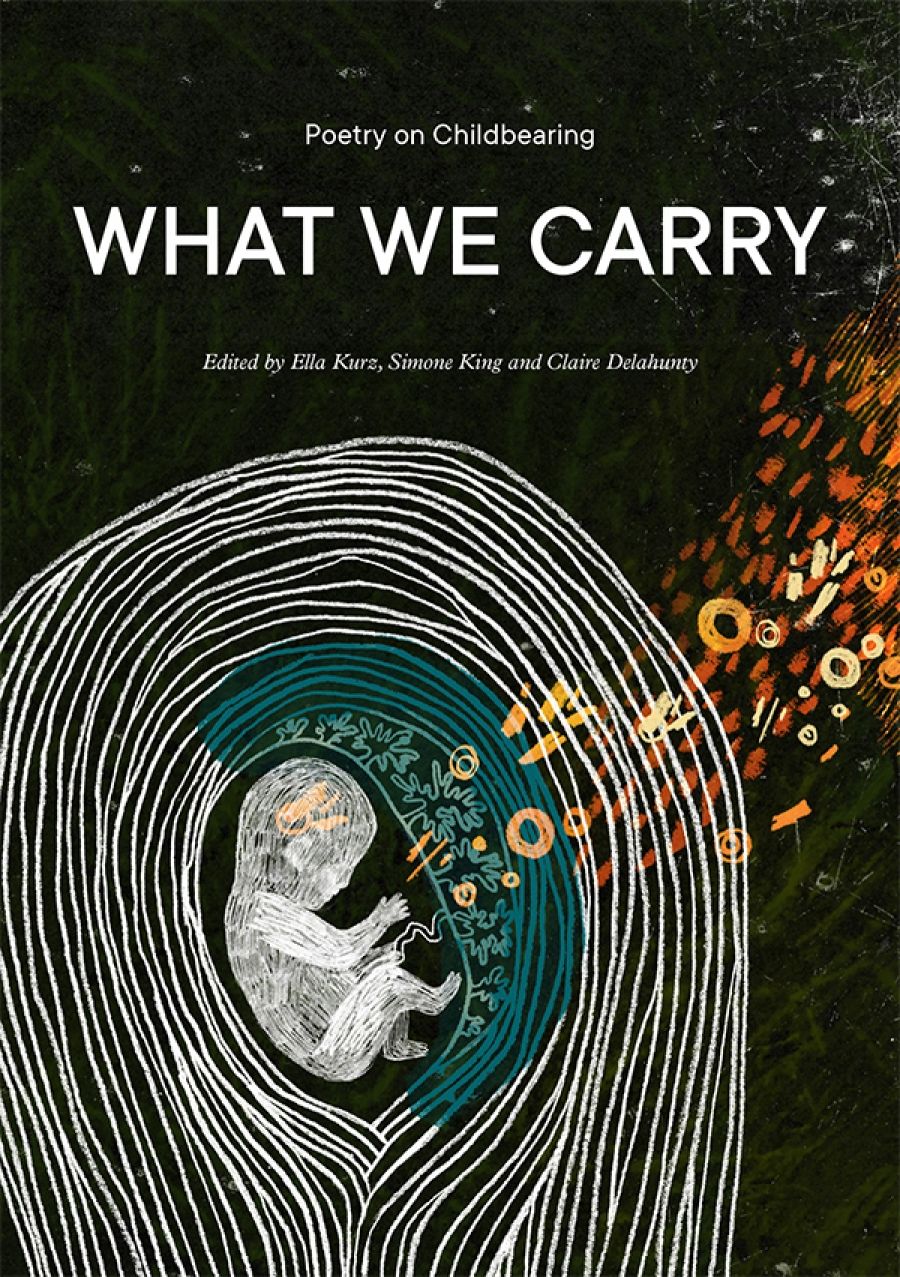

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jane Gibian reviews 'What We Carry: Poetry on childbearing' edited by Ella Kurz, Simone King, and Claire Delahunty

- Book 1 Title: What We Carry

- Book 1 Subtitle: Poetry on childbearing

- Book 1 Biblio: Recent Work Press, $24.95 pb, 226 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/e4ryB1

A cogent introduction sets out the editors’ argument that procreation provides insight into human existence. They quote Alicia Ostriker’s assertion that to consider the experiences of motherhood as trivial or tangential to the real issues of life, or as irrelevant to the great themes of literature, is a misogynist training that we should all unlearn. This anthology goes some way to celebrating childbearing as a fundamental part of the human condition.

Through its inclusion of work from writers of different ages, ethnicities, genders, sexualities, and experiences, the collection offers a generous array of viewpoints. The editors have selected work from both established and emerging writers. As with many anthologies, the quality of its poetry is uneven, but there are enough complex and striking works to carry the reader’s attention, including Maria Takolander’s ‘Unborn’:

… It was then

I felt the tide come in, bearing silt stirred from the

fetid sea floor, old with starfish and eel bones. The

moon, for nine months, did not care to claim it again.

The book is arranged in sections of clearly delineated themes, such as conception and (in)fertility, pregnancy, loss, birth, and choice. This guides the reading experience quite explicitly; it’s hard to read a poem in the section called ‘Birth’, for instance, without bringing along your own experiences or preconceptions about the process of birth. It inevitably forces a close comparison of poems on similar themes that sometimes doesn’t do justice to an individual poem.

Each titled section comprises one or two subsections with individual titles, phrases taken from a poem therein. For example, ‘Loss’ contains the subsections ‘Thawed promise’ and ‘My womb to my heart’, and ‘Postpartum’ is divided into ‘Unmaking’ and ‘Love and wonder’. While these are less prescriptive than the main section titles, I felt that the ordering was at times more constraining than necessary. Sometimes the specific focus of a section can be a strength instead of a limitation, in allowing ample space for diverse voices on a particular theme. Strong poems stand out, such as Michelle Cahill’s ‘Stepping through Glass’: ‘The alien song of a bird along the fire trail, / the wet flag of our labrador’s tongue / and my thoughts like fallen, burnt-out logs.’

Many poems have an autobiographical quality. It is fascinating to observe this in poets like Judith Bishop and Anne Elvey, whose other work is often less direct and more subtle in subject and style. Perhaps this reflects the overwhelming emotional and physical investment required in all aspects of childbearing, from trying to conceive to holding a baby in your arms. This is not necessarily a drawback, though some poems by less skilled writers, with a confessional voice and a narrative structure, read more like cut-up prose and are thus less forceful.

The anthology rightly features substantial poems relating to infertility and loss, and the choice not to have children, as expressed in Jacqui Malins’ poem: ‘a knowing so sure you were not for me. i / wondered what kind of person. of / woman my certainty made me? / it never wavered.’ Some of the poems on infertility and miscarriage are heart-rending, such as Nandi Chinna’s ‘Another Month’: ‘Every time the moon grows huge, / I’m labouring again in my stony field, / sowing the crop that never bears fruit.’

Poems cover post-natal depression, breastfeeding, and exhaustion, as well as the joy and wonder of a having a new family member. Others touch on the medicalisation of birth, and Audrey Molloy captures the experience of feeling like an object under the medical gaze: ‘the cargo / of her uterus illuminated / like a fossil on a dig.’

Poetry by Indigenous writers bookend the anthology, and other works bear witness to the abuse of Aboriginal women by white men, and the subsequent pregnancies. The steadfast lines of culture and belonging between generations of women shine through, such as in the final poem, Natalie Harkin’s ‘Thread offerings | For my children’: ‘no matter how far back or forward you go / I am with you always you will find us and this beginning can / never end.’

There is a welcome seam of humour in lines from Felicity Plunkett’s ‘Soft-tissue Stitching’ – ‘The partners, as if on a school excursion, are invited / to take turns inhaling gas and air’ – and in Esther Ottaway’s portrayal of the foetus:

My difficult houseguest

tramples the body’s furniture,

dances until late,runs up enormous bills

of oxygen and blood

Readers will have their own opinions on how many poems by male poets should be included – here there are a scattering. Like those by female poets, they differ in quality but in general they are not the most arresting in the collection. A couple suffer from being overlong and lacking the sharpness of poems like Elvey’s ‘Birth’: ‘Between my / thighs your / scream / slides.’

There are also impressive poems by Petra White, Melinda Smith, Eileen Chong, Lucy Dougan, and LK Holt, among others. Overall, the multiplicity of experiences examined poetically is a strength of this book. What We Carry is a compelling anthology that is hard to read lightly or without emotional engagement – or even without remembering the prickle of rising milk.

Comments powered by CComment