- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Scott-land

- Article Subtitle: The ubiquitous Walter Scott

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Walter Scott, born on 15 August 1771, turns 250 in 2021. This event has been celebrated in Scotland with events such as a ScottFest at ‘Abbotsford’, his home, and a major international conference. But Scott, almost certainly the most popular and widely known author in the world in the nineteenth century, fell disastrously in public and critical esteem, to the point that E.M. Forster, in his influential Aspects of the Novel (1927), could sum him up with the wearily dismissive question ‘Who shall tell us a story?’ and the equally dismissive answer ‘Sir Walter Scott of course’. For Forster, Scott had ‘a trivial mind and a heavy style’.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

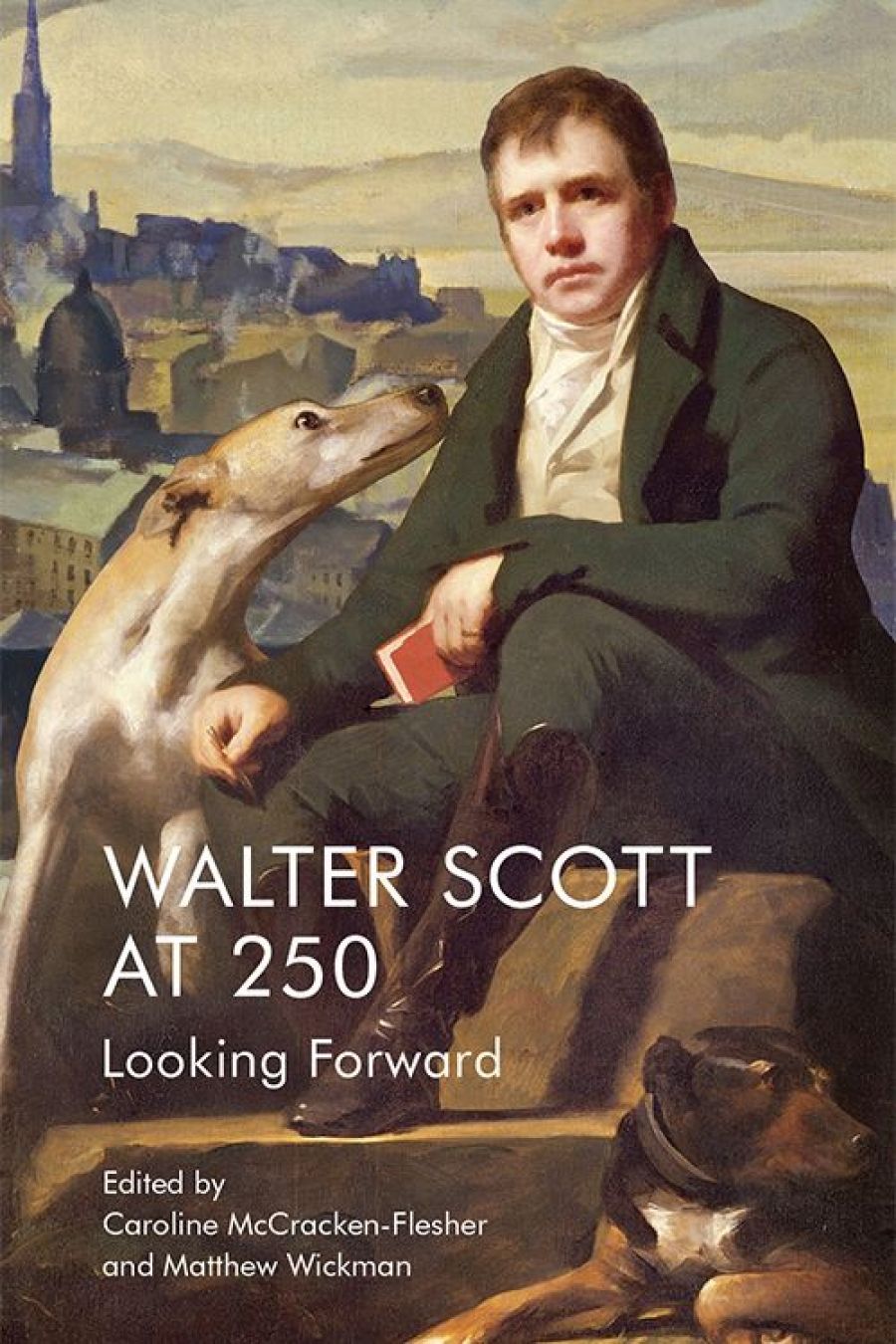

- Article Hero Image Caption: Walter Scott, the Scottish historical novelist, poet, playwright, and historian (photograph via Britannica)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Walter Scott, the Scottish historical novelist, poet, playwright, and historian (photograph via Britannica)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Graham Tulloch reviews 'Walter Scott at 250: Looking forward' edited by Caroline McCracken-Flesher and Matthew Wickman

- Book 1 Title: Walter Scott at 250

- Book 1 Subtitle: Looking forward

- Book 1 Biblio: Edinburgh University Press, £75 hb, 239 pp

When I first encountered Scott through my aunt and uncle’s collection of the Waverley Novels, everyone I knew had heard of him and could name at least Waverley (1814) and Ivanhoe (1820) among his works. This is no longer the case, though Tony Blair nominated Ivanhoe as his favourite novel. It is true that Scott’s critical reputation, as least in universities, has risen again over the past fifty years or more, but that hasn’t translated into a revival of his popularity with readers. The contrast with Jane Austen is striking: as Scott’s readership has fallen over the last two centuries, Austen’s has risen spectacularly. Scott will never recover the position he held in the nineteenth century, but it is to be hoped that this anniversary will bring some attention and some readers back to him.

Against this background comes Walter Scott at 250: Looking forward, the most wide-ranging of several books on Scott that have appeared in 2021. It is a big ask to produce a book that proclaims itself to be ‘looking forward’ when its subject is best known as a historical novelist. Yet all the writers in this collection of ten fascinating chapters aim to show the ways in which Scott and his work can be said to be looking forward. Like so much of recent critical writing, they demonstrate how complex Scott’s writing is and how far he is from having a trivial mind or even a heavy style.

Five chapters examine the novels for the way they provide insights relevant to our troubled present. Somewhat surprisingly, two chapters that bring Scott close to our lives today do so through economics. Anthony Jarrells suggests that Thomas Piketty might have usefully looked at Scott, just as he looks at Balzac and Austen, for information relevant to his Capital in the Twentieth First Century (2013). As Jarrells neatly puts it, ‘Piketty, the bestselling economist who writes about novels, leaves out Walter Scott, the bestselling novelist who writes about economics.’ Alongside this, Celeste Langan draws a parallel between Scott’s compulsion to pay off his debts by unremitting work on his massive life of Napoleon (1827) and the pressure on academics in the neo-liberal university of today to write more and more to pay their ‘debt’ to funding agencies and the universities that employ them, a message with implications that extend beyond the academy.

Taking different approaches, Susan Oliver makes the ‘bold claim’ that Scott ‘speaks meaningfully to a twenty-first-century anthropogenic world’ and supports her claim by a specific study of his references to species loss; Matthew Wickman takes Scott’s novel Redgauntlet (1824) as a treatment of the unthinkable, relevant to our world as it faces the unthinkable things that might happen now and in the future; and Fiona Price links Scott’s treatment of political and gender performance to our own time ‘preoccupied by “gender performativity”, “precarious lives” and empty political theatricality’.

Another three chapters find looking forward within the novels themselves and in our experience of reading them. Ina Ferris discusses how reading is itself a forward-looking activity as we progress towards the end of the text, but she also shows how Scott controls the pace, often as we follow the characters moving slowly through the landscape. Penny Fielding explores the intriguing notion of the future anterior – what will have happened in the future but has not happened yet – in The Bride of Lammermoor (1819). Ian Duncan considers how as readers we anachronistically experience the past as part of our present: through the act of reading we place our modern consciousness within the past. All three are dealing with how we experience history through reading historical fiction, an important issue today when novels set in the past are again a popular genre.

The remaining two chapters look forward in yet other ways. Alison Lumsden discusses what we might learn and have already learnt from the new edition of Scott’s poetry now underway, and in particular how the many and varied notes, an integral part of Scott’s long poems, seem to act as a reminder that no one account of the past is sufficient in itself. Finally, Caroline McCracken-Flesher reminds us that, from Scott’s time to the present day, visitors to ‘Abbotsford’ have so often ignored the presence of the women who have made the household function over two centuries. It is a timely reminder. In recent years Abbotsford has been carefully restored and equipped with a splendid visitor centre. Perhaps a visit there can bring people close to Scott and his world and maybe encourage them to start reading his writings again.

The anniversary and this book prompt me to think about Scott in Australia. The evidence of his huge popularity and influence in the past is easy to find. All we need do is look at the map. Anyone who lives in the many towns or suburbs in Australia called Ivanhoe, Waverley, or Abbotsford participates – knowingly or, more likely, unknowingly – in the commemoration of Walter Scott. For anyone who wanted to associate their residence with a favourite writer, Scott had the enormous advantage of having deliberately chosen names for the heroes of two of his best-known novels that had no earlier literary associations, as well as coining a previously unused name for his house. Giving a house, a suburb or a street one of these names confers on it an unambiguous association with Scott. The same is true of less common names like Deloraine, Rotherwood, Ellangowan, and Lochinvar. Moving beyond these most visible of signs to Australian newspapers, a search of Trove will reveal thousands of references to Scott and his novels and poems. Some of them exhibit a certain ignorance of his work – only a year after the publication of Ivanhoe, a novel set in twelfth-century England, ‘the tune of Ivanhoe’ apparently ranks among ‘Scotch tunes and dances’ at a ball in Sydney – but other references show deep knowledge of his writing. Works derived from Scott, plays and burlesques, poems and paintings, also figure prominently in the newspapers. Australian writers adopted pseudonyms from Scott, including Rolf Boldrewood, who took his name from Scott’s poem Marmion (1808), and others embraced Scott’s medieval world to provide a literary ancestry to their writing, as Louise D’Arcens, for example, has shown in her Old Songs in the Timeless Land (2011).

Scott in fact had strong personal connections with colonial Australia: he wrote to Governors Macquarie and Brisbane, and supported people like George Harper, who gave the name ‘Abbotsford’ to his own house near Picton, and the convict Andrew Stewart, a minor poet whose life was saved by Scott’s intervention after he was condemned to death. However, it was Scott’s literary influence that is his most important contribution to Australian life and culture.

Of course, the imposition of so many of Scott’s names on the landscape reflects how deeply his writing was implicated in the colonial enterprise. In a land far from home that they thought held no history, the new arrivals sought to endow that land with familiar associations. Scott’s work offered multiple associations with literature and history, but writing these names onto the map inevitably involved overwriting Aboriginal names which had been there for centuries before. Using a name derived from Ivanhoe, such as Rotherwood, endowed a place with a spurious medieval pedigree that completely ignored the much older Indigenous connection with the land. Given the implication of Scott’s writing in the erasure of earlier Australian Indigenous identity, what, then, can he offer us today? Ironically, it is precisely in the area of national identity that Scott can perhaps offer us a model. His writing was so influential in establishing modern Scottish identity or identities that Stuart Kelly’s recent book is named Scott-land, a pun used by others as well. Astoundingly, Scott not only helped define (some would say simply ‘defined’) Scottish national identity for his age and ours, but also contributed powerfully to the definition of English identity. His most influential novel, Ivanhoe, presented an enduring myth of English identity as the merging of Anglo-Saxons and Normans. But Scott did this by looking to the past of both nations. He was not afraid to confront (if not always full on) the dark moments of the past, like religious persecution in seventeenth-century Scotland or Norman oppression in medieval England. Walter Scott at 250 offers many ways to connect Scott with our world today, but if we could look for one single message in the book it would be that to understand the present and look forward to the future we must look to the past, including its darkest moments. It is a message with continuing relevance for us in Australia.

Comments powered by CComment