- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Feminism

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Complaint as inheritance

- Article Subtitle: Sara Ahmed’s ongoing intellectual project

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 2016, feminist and queer theorist Sara Ahmed resigned from her post as professor at the Centre for Feminist Research at Goldsmiths, University of London, in protest against the failure to address sexual harassment at her institution. Given that she was at the peak of her career and working in a centre she had helped to create, hers was a bold and surprising move, but also entirely consistent with her feminist politics. In one way or another, Ahmed has been writing about this decision, its causes and effects, ever since: first on her blog feministkilljoys; as an example of a ‘feminist snap’ in Living a Feminist Life (2017); in relation to diversity work in universities in What’s the Use: On the uses of use (2019); and now most directly in Complaint!, her tenth book.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Zora Simic reviews 'Complaint!' by Sara Ahmed

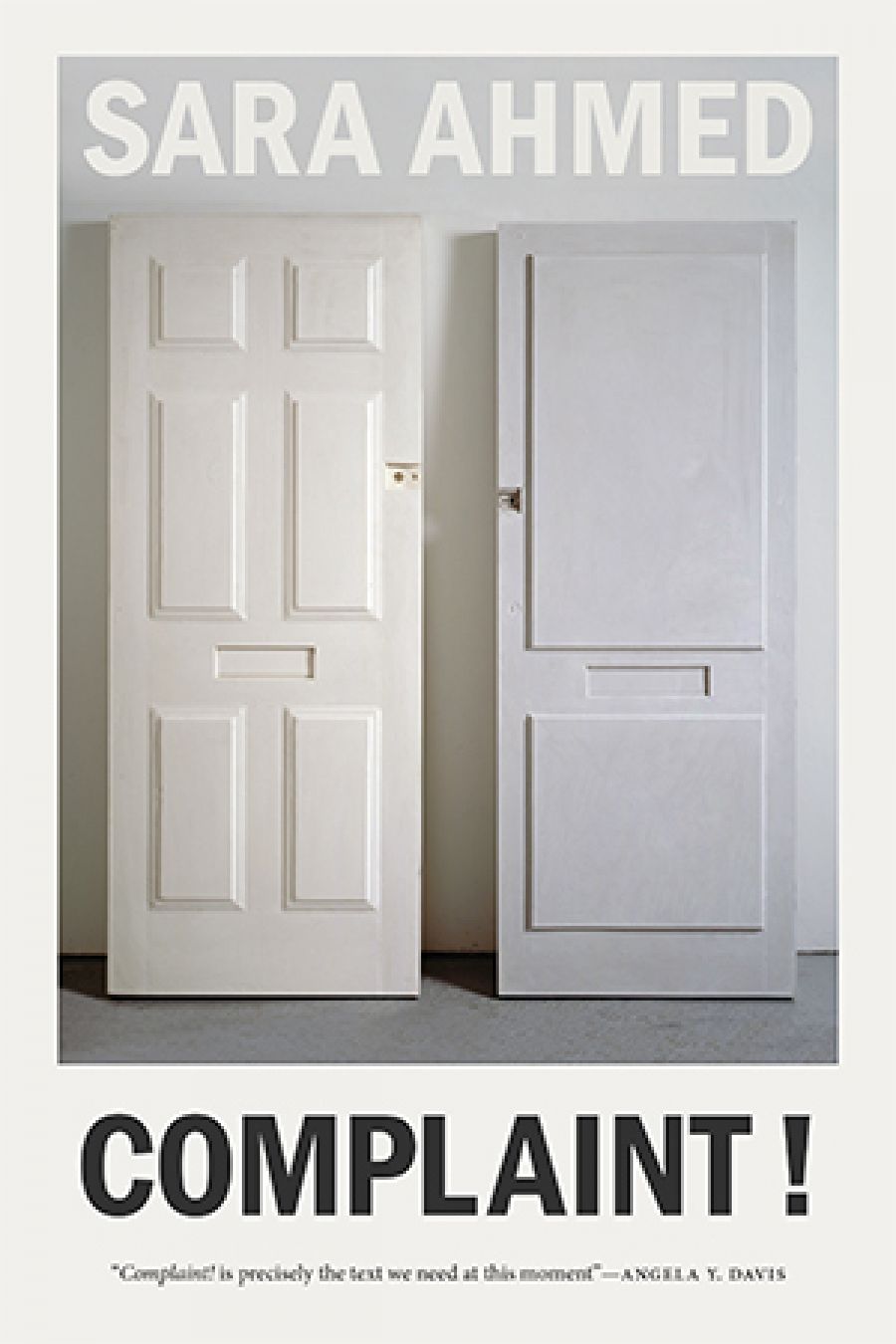

- Book 1 Title: Complaint!

- Book 1 Biblio: Duke University Press, US$29.95 pb, 376 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/vn4GjA

The subject of complaint is classic Ahmed territory rather than a new direction. Ahmed is prolific, but her work is best appreciated as an ongoing political and intellectual project. One book begets the next, and within each nest earlier concerns and theorising. As a site of analysis, the phenomenon of institutional complaint allows her to address her perennials, including feminism, the university, the cultural politics of emotion, and the designation and revaluation of ‘wilful subjects’ such as ‘feminist killjoys’ and ‘complainers’. Once again, her most treasured thinkers are Black feminists and feminists of colour, including Audre Lorde, whose famous essay ‘The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House’ (1984) offers both an analytic frame and inspiring evidence of what taking a stand, or making a complaint, can turn into. As per usual, Ahmed is on the side of students, against contemporary tendencies – including among their teachers, some of them feminists – to view them as too coddled, too sensitive or ‘woke’, and/or powerful enough to topple a career with a single tweet or complaint.

Ahmed reveals that she had embarked on this project before her resignation, but her decision ‘changed the nature of the research as well as how I could do it’. Similarly, Ahmed’s project preceded #MeToo going viral, but was inevitably caught up in it. Many people contacted her to share their stories, and Ahmed cultivated listening with what she calls ‘a feminist ear’, that is ‘to hear what is not heard, how we are not heard’. The foundation of Complaint! is interviews with forty students, academics, and administrators variously involved with formal complaint procedures. Not all complaints relate to sexual harassment, or not exclusively; sexism, racism, and bullying frequently recur, as does the complaints process itself. Ahmed is also alert to how some requests (such as reasonable adjustments for staff and students with disabilities) or even certain words (‘race’, ‘racism’) can be received as a priori complaints. There is no pretence here to social science and a representative sample – that’s not the point. Ahmed describes her task as receiving and sharing stories of complaint, a more radical undertaking than it may appear at first glance.

Sara Ahmed at Geneva University in 2019 (Rama/Wikimedia Commons)

Sara Ahmed at Geneva University in 2019 (Rama/Wikimedia Commons)

In taking complaints seriously, Ahmed reveals what so-called complainers are up against (opaque or zombie policies, closed doors, dismissive language, collegiality, and other forms of gate-keeping); where complaints most often end up (folders, filing cabinets); and who so-called complainers are more likely to be (a clue: not straight white men). Complaint is addressed as labour, and as trauma, including in instances where complaints are formally ‘resolved’. In collecting complaints, Ahmed considers them as testimony, as biography and as history, including as part of the ‘counterinstitutional knowledge of how universities work, for whom they work’. Complaint can be generative; for instance, a trans lecturer experiences discrimination, discovers there are no specific guidelines for trans staff, and helps initiate a conversation about their necessity. The people who share their stories – from undergraduate students through to professors – are recognised as astute theoreticians of their own experience, and of institutional power. In quoting them at length, Ahmed adds new terms like shadow policies and coercive intimacy to her own evolving critical vocabulary.

Integral to Ahmed’s anatomy of complaint is her dissection of how institutions respond to them. In this task, she builds on her earlier work on, and experience of, how diversity and equality are managed in higher education, but there is wider salience. Many readers will recognise the non-apology apology, ‘strategic inefficiency’, which can slow down processes to a glacial pace, and the implementation of woefully inadequate new policies or training – like the federal government’s recent introduction of optional one-hour sexual-harassment training for MPs. Ahmed’s analysis is characteristically precise (‘Creating evidence of doing something is not the same as doing something’), but where she really hits her stride is in her treatment of less obvious strategies of containment. These include ‘nonperformative’ nods, warnings about ‘what would happen’, ‘blanking’ as though the complaint never happened, and diversionary caricatures of the ‘complainer’. She argues, for example, that the figure of ‘Karen’, the ‘privileged white complainer’, can work to ‘stop complaints about racial harassment from being heard’. What Ahmed describes is ‘institutional fatalism’, analogous to how violence within a family can be rationalised, ‘either by being projected onto strangers who can be removed (as if to remove them would be to remove violence) or by being made familiar and thus forgivable’. This is audacious but persuasive critique, which accrues its power by stealth.

Complaint! is dense with insight, but admirably lucid. Ahmed’s propensity for wordplay – which can be distracting – is here put to good use, as she burrows down into the common phrases used to describe and dismiss complaints and complainers (rocking the boat; broken record) and to justify unacceptable behaviour (perk of the job). Through the portal of ‘complaint’, Ahmed advocates for intersectional feminism, for ongoing transformation of universities, and for collective action. In regards to the last, Ahmed takes inspiration from the archives of complaint activism and in solidarity with former students and colleagues in a co-authored chapter titled ‘collective conclusions’ – rather than workplace unions, which are barely mentioned (Complaint! is not that kind of book). Ahmed’s loyalty is to the complainers, not to the institutions they continue to push up against.

Comments powered by CComment