A six-year-old in Canada memorises a poem written by Li Bai in the eighth century. She recites its twenty syllables perfectly in the Mandarin she studies at Saturday Chinese school, but beyond a mechanical conversion into English, makes little sense of it. Murmuring the poem’s words then holding her breath as though waiting, her mother tries to help.

Decades later, Gillian Sze realises her mother wanted not to translate the words but to translate poetry. Across languages and centuries, over the bridge from Chinese characters to the Latin alphabet of English, the small child presses forward into the strange terrain of the poem, a thing William Carlos Williams described as ‘made up of … words and the spaces between them’.

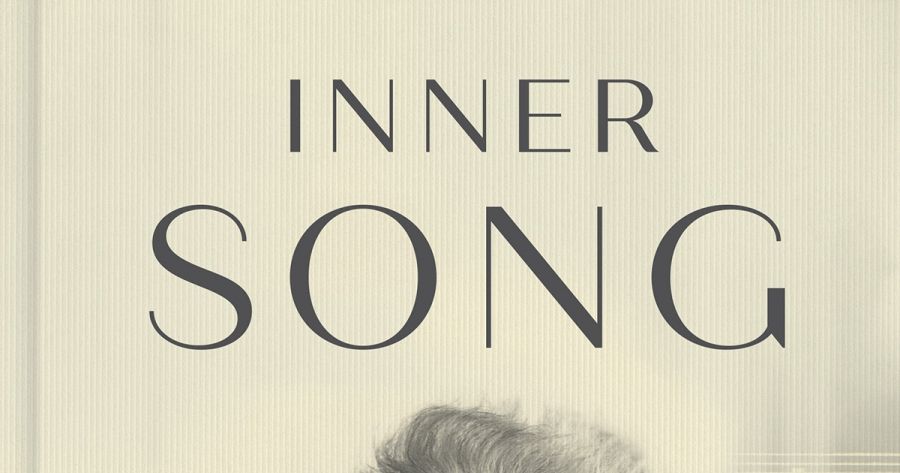

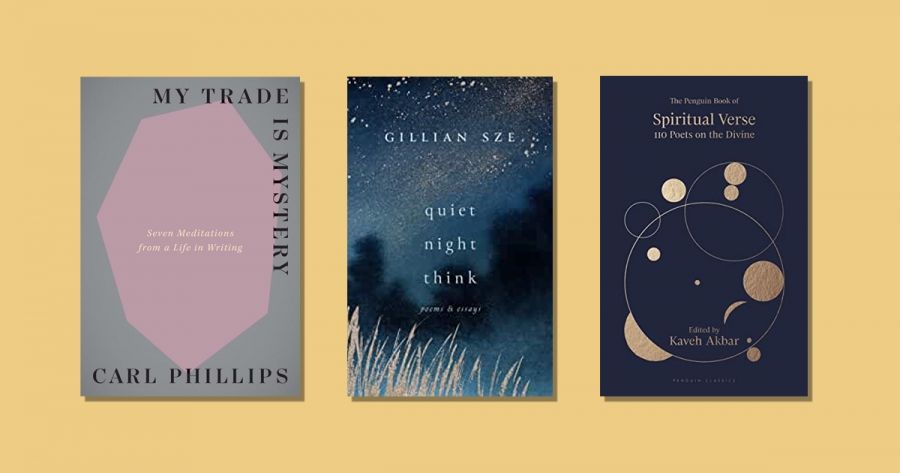

Around the same time, a young Latin teacher begins writing poetry to wrestle his way ‘toward a clarity about something I couldn’t understand in any other way’. My Trade Is Mystery: Seven meditations from a life in writing (Yale University Press, $30.95 hb, 112 pp) contains seven meditations as, decades later, Carl Phillips, the author of fifteen poetry collections and several books about poetry, looks back to the time he began to explore, without ‘map or compass’ the ‘strange territory’ he found himself in, or found in himself. A poem’s ‘record of interior attention paid’ shows ‘evidence-like tracks’ of that quest.

Phillips thinks of the title of Amy Clampitt’s final collection, A Silence Opens, as he reflects on Lucille Clifton’s poem ‘[evening and my dead once husband]’. The speaker asks her dead husband about anxiety, illness, the ‘terrible loneliness / and wars against our people’. In reply, he spells out with his fingers: ‘it does not help to know’.

Phillips approaches a question with the gently enquiring syntax that shapes this wise work: ‘Is it maybe better not just to respect but to continually embrace knowledge’s limits? Past which, like the sea where the land gives out, yes, a silence opens.’

When silence opens, as when darkness arrives, our perception alters. ‘What do darkness, stillness, silence make possible?’ asks Kaveh Akbar. He wraps each poem in The Penguin Book of Spiritual Verse: 110 poets on the divine ($35 hb, 400 pp) in an invitation or question, footprints into the poem’s territory. Here, he explores a poem by sixth century bce Buddhist nun Patacara, who extinguishes a candle to help concentrate her mind ‘the way you train a good horse’.

For Akbar, migrating from Tehran to an America ‘actively hostile to my existence’, poetry became ‘a place I could put myself’. He spoke Arabic, his third language after Farsi and English, only in prayer. ‘God’s own tongue’ might ‘thin the membrane’ between himself and the divine. His quiet, acute editorial comments feel like an overheard whisper, a loose thread of prayer.

Akbar scours a vast archive of doubt and yearning, and conducts voices in hymns of despair, prophecy, petition, and exaltation. Acknowledging that curatorial choice emerges from ‘one vast and unprecedented life’, he says: ‘I claim no objectivity.’ He aims not to fix canonicity but to break it open, ‘in opposition to the colonial impulse’. Unlike the tight fist of colonisation, Akbar’s method is to loosen and include. He looks beyond categories (time, faith, nation, gender) toward ‘a shared privileging of the spirit and its attendant curiosities’. His interest in the body in prayer, the idea ‘that the ecstatic might (or must!) include the body’, is evoked in the anthology’s expanse and sinuousness.

These books seem to speak to one another. Reading them, I cross between known and unknown places, poets, and poems. Names bounce among them (Emily Dickinson, Lucille Clifton, Rainer Maria Rilke). On long walks I listen to Phillips reading My Trade Is Mystery, then return to its pages. Each book exchanges certainty’s closure for mystery’s openness and invites a translation of self and thought. Writers are always translating ourselves from reader to writer, and Sze, Phillips, and Akbar step slightly aside from their own poems to consider poetry. As I write this, hoping to be the kind of reader Phillips identifies as those ‘we write toward, a small hand against disappearance’, I also reach for such readers as I inhabit poetry’s strange territory, where meaning, Phillips writes, ‘is unfixed, ever changing’.

Akbar’s poems are placed to speak to one another. In ‘God’s One Mistake’, Oodgeroo of the Noonuccal situates human discord – ‘[i]ntolerance, unkindness, cruelty’ – amid a peaceful more-than-human world. God’s ‘one mistake’ is the gift of free will, so often making humanity ‘[u]nhappy on the earth’. This line is followed by ‘There was earth in them and / They dug’, the opening of a poem by Paul Celan.

The poets’ lines sit adjacent like parts of a severed couplet. Hélène Cixous described Celan’s ‘writing that speaks of and through disaster such that disaster and desert become the author or spring’. The Shoah, the ‘unimaginable violence inside the Nazi death camps’ (as Akbar says) is a product of the human free will Oodergoo questions. Those who dig call out: ‘O someone, o none, o no one, o you.’

Poems reach out to ‘no one’ (some- or no-one, you or me). Like messages in bottles cast into the sea, they might reach shoreline or heartland, Celan wrote. Readers wait for them. Akbar’s words resonate with Phillips’s when he describes preferring poems ‘certain of nothing, poems that [embrace] mystery instead of trying to resolve it’. For Sze, too, poetry offers an opening: ‘Creative space. Emotional space. A space for possibilities.’

Sze’s tentative ongoing reading of ‘Quiet Night Think’ (Quiet Night Think: Poems and essays, ECW Press, $21.95 pb, 92 pp) cultivates patience and agility. Line breaks remind her of ‘the fractured dialects I grew up with, the skipping from language to language, the acrobatic ear’, mapping a way toward ‘some hiccupped notion of home’. The ‘hesitation’ she finds in William Carlos Williams engenders ‘slow, careful deliberation that sets the reader aglow’. Through false starts and mistranslations, Sze comes to recognise the futility of containment, in texts and life. A ‘fissure ceases to be a flaw’, opening instead to new possibility. Yet, writing as a soon-to-be mother, spaciousness contracts. Time, too, narrows. For the writer whose energy is diverted to ‘the present, the vulnerable, to those whose cries are for me alone’, how might spaciousness be possible? Might the poem itself, like a child, insist on (and teach us) ‘our attention, our un-rest’?

Perhaps poetry is both cradle and archive of uncertainty, space where doubt’s thrum might be listened to rather than muted; might be cherished, amplified and even cultivated. Toni Morrison described her interest in writing into ‘the complexity, the vulnerability of an idea’ (not certainty, ‘that would be a tract’). German artist Gerhard Richter, whose paintings’ gauzy grain blurs the certainty that can rear up into fascism, says: ‘I like the indefinite, the boundless; I like continual uncertainty.’

‘Other qualities,’ he adds, ‘may be more conducive to achievement, publicity, success; but they are all outworn – as outworn as ideologies, opinions, concepts and names for things.’ Phillips, too, is wise about narrow paths to high places, advising ambition not in the sense people ‘too easily confuse with competition’, but something that has ‘nothing to do with other people and their perceptions’.

For Akbar, a time of addiction was one of ‘absolute certainty’. Afterwards, he was drawn to nuance and doubt. Now, though, ‘irony is the default position of the public intellectual’, and language is deployed: ‘the great weapon used to stifle critical thinking is a raw overwhelm of meaningless language at every turn’. ‘Passionately absolute’, it tells us that ‘immigrants are evil, climate change is a hoax, and this new Rolex will make you sexually irresistible’.

For Tracy K. Smith, poetry can be a language beyond that, and beyond ‘our day-to-day errand-running and obligation-fulfilling’. Beyond ‘glib, facile, simplistic and prefabricated’ language, past the sales pitch that pulls us ‘away from the interior’, poetry can ‘inoculate us against the catchy, inescapable, strategically biased language of the market’.

Perhaps instead of the language of selling, poetry is ‘trade’, in the double sense of exchange and skill.

Perhaps, instead of the commodification and sale of certainty offered by Big God, we might find in poetry the spiritual fuel of uncertainty, doubt, porousness, vulnerability.

Perhaps that vulnerability is an aperture, that porousness an admission – in the double sense of acknowledging and letting-in – of mystery.

Perhaps, in the double sense of splitting apart and adhering to, poetry cleaves (to) mystery.

Phillips suggests: ‘To acknowledge limits to what we can know about a thing – to acknowledge mystery – is not, to my mind, an admission of defeat by mystery, but instead a show of respect for it.’ Using the term ‘as secularly as possible’, he describes this as a ‘form of faith… in art’s ability to know’.

Poetry gives us a syntax of uncertainty. For Sze, it is in restive interleaving of lyric prose with pared poems. In Phillips’s poetry and prose, there are traces of his training as a classicist. Latin has a largely free word order. Learning it involves memorising words’ declensions and conjugations the way a musician memorises scales. Each word has shades and tones (tense, gender, case) to fit the sentence. Rigour and mobility are poised, the way a poem’s form might hold fragments even as they scatter and flit, the way a prayer’s words might move at the edges of the unknown.

Akbar makes transparent what more conventional anthologies conceal. Aware that readers might ‘object to the omission of their favourite poet of the spirit’, he hopes to ‘at least make a pass at accounting for the vast complexity of the human project of spiritual writing’. His ‘modest study’ of the ways poets ‘wrap language’ around the unknowable is exhilaratingly full of discovery and rediscovery. It ventures ‘across time and civilizations’, beyond Eurocentric and male-dominated accounts of the spiritual, past shame and fear that attend the magical and spectral. This results in a blazing expanse of words – and the spaces between them, the losses and silences of the unspeakable, ineffable and awesome.

Paradoxically, Sze’s deep exploration of one poem, ‘Quiet Night Think’, is similarly expansive. The title of Li Bai’s poem 靜夜思 (Jìng Yè Sī) is translated as ‘Quiet Night Think’, ‘Thinking on a Quiet Night’, ‘Quiet Night Thoughts’, ‘A Quiet Night Thought’, ‘Contemplating Moonlight’, ‘Brooding in the Still Night’, or ‘Lamentations in the Tranquility of Night’. Its limitless shades of meaning provide an ongoing lesson in the mobile and shifting ground of the poem.

Akbar’s calling forth of ‘pivotal samples from my own reading and discovery’ begins with a poem by the earliest attributable author of all human literature, twenty-third century bce Sumerian high priestess Enheduanna. More than two thousand years before Sappho, she makes, Akbar says, ‘a dizzy stagger’ in ‘ecstatic awe’ at the divine, just as replete with desire.

Sappho’s work burnt with the Great Library of Alexandria and exists in recalled fragments. Its salvaged slivers are traces of something once thought and felt, now ash. Legend has Sappho discovering poetry after finding the singing head of Orpheus, dismembered by the Thracian Maenads, on the shore. If this inheritance was song continuing after violence, her bequest is a smouldering and achy catalogue of what we long to but cannot save.

Spiritual verse moves between wanting and not wanting, from Sappho’s: ‘because I prayed / this word / I want’ to Kind David’s ‘The Lord is my shepherd. I shall not want.’ It moves between compare and ‘false compare’ (or ‘beautiful false compare’ as Michael Ondaatje calls it). Of a section from the biblical ‘Song of Songs’ (‘I have compared thee, my love, to a company of horses in Pharaoh’s chariots’), Akbar notes its echo in Shakespeare’s ‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?’ On the other hand, Shakespeare, in sonnet 130, parodied the ridiculous swerve of blazonry’s metaphors from a lover’s features to coral and snow, perfume and roses.

For Celan, poems are ‘gifts to the attentive’. From our un-rest and our attention paid, beyond the limits of what we know, surrounded by what Akbar describes as ‘doubt, the divine, and the wide, mysterious gulfs in between’, yes, a silence opens.