- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Birds as bioweapons

- Article Subtitle: A history of the Smithsonians’s Pacific project

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1962, a small group of scientists from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC embarked on what would become the most ambitious biological survey of the Pacific oceans. Across seven years they travelled to more than 200 islands over an area almost the size of the continental United States. They banded 1.8 million birds, captured hundreds of live and skinned specimens, and collected ‘countless’ blood samples, spleens, livers, stomach contents. What became of most these biological samples has never been disclosed. The Smithsonian’s Pacific Project was, and remains, shrouded in secrecy. The scientists involved were left to guess at the aims of their research. They were mere subcontractors, following the directives of their funding agency: the biological warfare division of the US Army Chemical Corps. ‘To me, as a bird man, it was a wonderful breakthrough because it was a source of funds,’ said S. Dillon Ripley, the Smithsonian’s secretary during the project. ‘That’s all I know about it.’

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

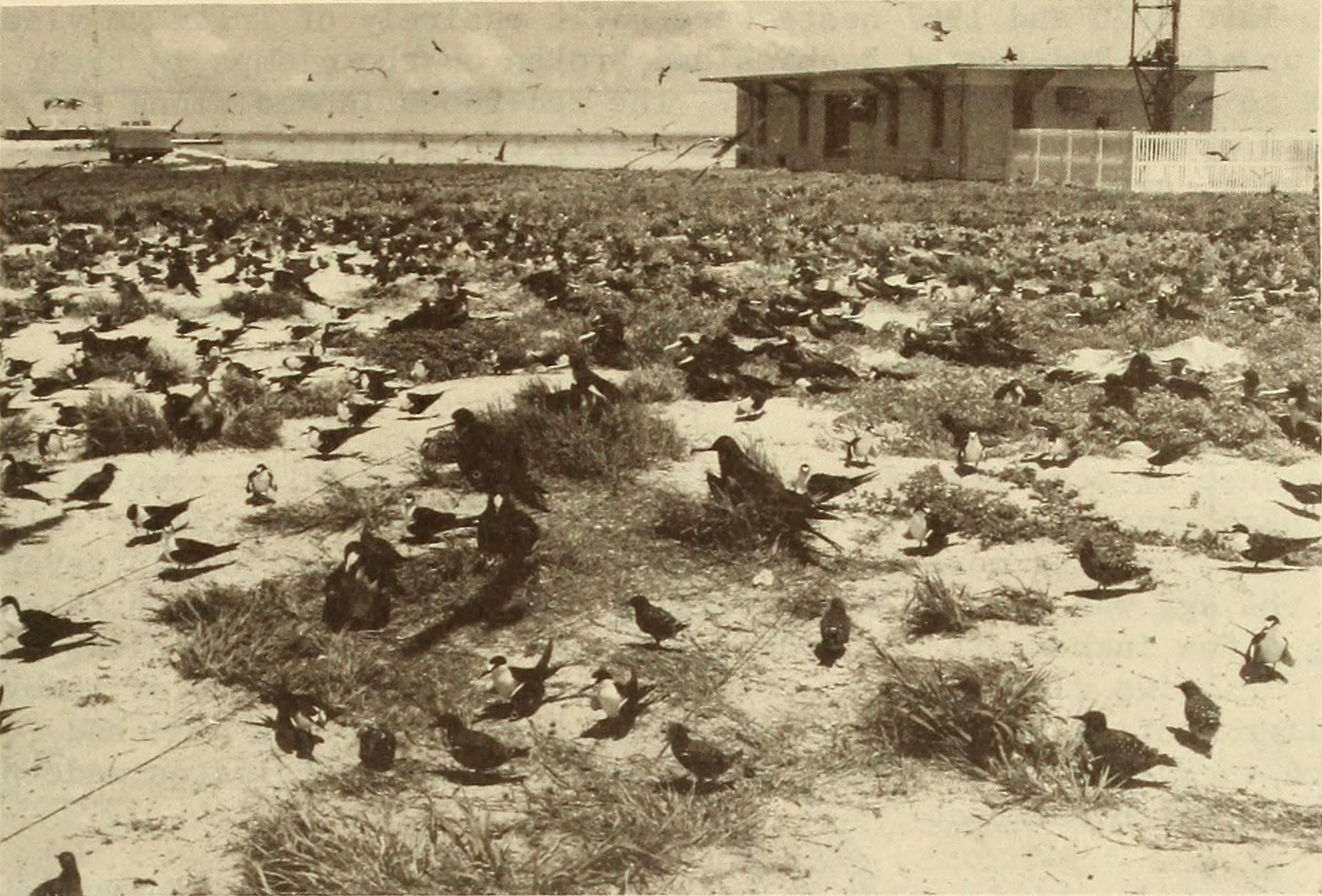

- Article Hero Image Caption: Great Frigatebirds nesting on ground on crest of hill east of transmitter building, Sand Island, Johnston Atoll, 1964. Sooty Tern adults and chicks surround the colony (Smithsonian Institution Press; National Research Council POBSP photo by A.B. Amerson/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Billy Griffiths reviews 'Science, Secrecy and the Smithsonian: The strange history of the Pacific Ocean biological survey' by Ed Regis

- Book 1 Title: Science, Secrecy and the Smithsonian

- Book 1 Subtitle: The strange history of the Pacific Ocean biological survey

- Book 1 Biblio: Oxford University Press, £22.99 pb, 187 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The strengths of the book are Regis’s interviews and correspondence with several of the key scientists, most of which took place in 1998 and 1999. These relate the highs and lows of remote work: the elation at being at the frontiers of Western scientific knowledge, alongside the exhausting, repetitive routine of counting and banding birds.

Most of the islands they worked on are little more than airstrips, barely rising above the water. The most intensively studied site was the Johnston Atoll in the North Pacific Ocean: the only dry land in more than 1,200,000-square kilometres of otherwise open ocean. It is an archipelago that has been built for purpose. Two islands are enlarged natural features; the other two are the invention of cranes, dredging machines, sheet steel pilings, and coral fill. ‘It is the oceanic equivalent of being “lost in space”,’ writes Regis. And it is that remoteness which made it a prized US military possession. Throughout the twentieth century, the atoll functioned variously as a submarine base, a transmitting station, a missile base, a launch site for atmospheric nuclear testing, and the staging point for a series of biological weapons trials. After the survey, Johnston Island was made into a chemical weapons storage site and, later still, an incineration facility for the disposal of chemical weapons such as sarin, VX, mustard gas, vomiting agent, and Agent Orange.

The archipelago also happens to be the breeding ground for more than half a million seabirds – and, since 1926, a federal bird refuge.

What was the army hoping to achieve by commissioning the Smithsonian survey? This question occupies much of the book. The army’s primary public justification for the survey was to minimise damage to US infrastructure. (Collisions with wires killed some two dozen sooty terns a day at the start of breeding season.) Regis believes the underlying purpose of Pacific Project was to find suitable remote locations for large-scale chemical and biological weapons tests. This helps explain the army’s interest in seabird migration patterns. If birds passed through clouds of active biological warfare agents, would they carry them on to human populations elsewhere?

But if this were the case, surely the army would have heeded scientific findings, rather than repeatedly ignoring them. The army staged the Shady Grove tests long before the Smithsonian team had been able to generate enough bird recapture data to establish migration patterns. Indeed, two members of the field team were still assiduously banding birds on the Johnston Atoll while F4-E Phantom jets were swooping to low altitudes nearby and releasing aerosolised live biological agents over the open ocean. As one of the core team members, Roger Clapp reflected: ‘If there’s anything we had shown it’s that you shouldn’t mess around with biological agents near Johnston. You could use frigate birds to kill off everybody in the Western Pacific if you wanted to.’

The secrecy surrounding the project leaves Regis to trade in ‘retroactive speculation’ to understand key events. While he is open about the available evidence, his reasoning is often contradictory and unsatisfactory. For example, he rejects the idea that the army was seeking to turn birds into bioweapons with the circular argument that mosquitos – which the army had already operationalised – were far more effective. While he charitably concludes that the survey was ‘an exercise in due diligence’, he is puzzled by the army’s decision to disseminate the tularemia pathogen despite knowing that terns and noddies ‘were highly susceptible to infection and the lethal consequences thereof’. And he finds the army’s release of clouds of Q fever microbes – to which local human populations had no immunological defence – ‘the most difficult single feature of the case to understand or explain’.

Regis’s naïve view of military intentions is perhaps best revealed through his lauding of the army’s environmentalism, which he describes as being ‘well ahead of Rachel Carson’. This is a difficult to argument to swallow in a book that discusses atmospheric nuclear testing, the clubbing of sooty terns for sport, and the mass asphyxiation of 18,000 incubating albatrosses (about five per cent of the world’s population) to construct three runways on Sand Island.

The Pacific Project ultimately came to an end with Richard Nixon’s termination of the US biological and chemical warfare program in 1969. It was a decision forced by growing international condemnation of the use of Agent Orange in Vietnam and the more local revelation that the army had been transporting leaking chemical munitions across the country, loading them onto ships, and then scuttling them at sea, in a project known as Operation CHASE (cut holes and sink ’em).

When the Smithsonian’s connection to the American germ warfare program was revealed in 1969, it caused a public furore. Smithsonian officials sought to minimise the connection – and so, too, does Regis, describing the ‘scandal’ as a ‘nine-day wonder’: a ‘minor failing’ with ‘little staying power’. A more substantive history might have teased out the moral quandaries of military sponsorship and the Smithsonian’s continued acceptance of defence contracts in the decades that followed the Pacific Project. A more contemporary assessment of the survey might have reflected on what we have learnt about the destructive power of live biological agents in the age of Covid-19 and H5N1 bird flu.

Comments powered by CComment