- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Wasee A-Crim

- Article Subtitle: The enigmatic fast bowler

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Sharply observed mimicry of sporting commentary is a niche comic form, but from the late 1980s, Australian comedian Billy Birmingham took it to chart-topping ubiquity with a series of recordings that gathered his small legion of impersonations under the sobriquet The Twelfth Man. Most famous were his recreations of a goonish Nine Wide World of Sports team from that golden age of television cricket commentary in which an ecru/ivory/white/cream-blazered Richie Benaud led the likes of Bill Lawry, Tony Greig, Ian Chappell, and Max Walker. Birmingham had the vocal measure of all of them, to genuinely hilarious effect.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jonathan Green reviews 'Sultan: A memoir' by Wasim Akram, with Gideon Haigh

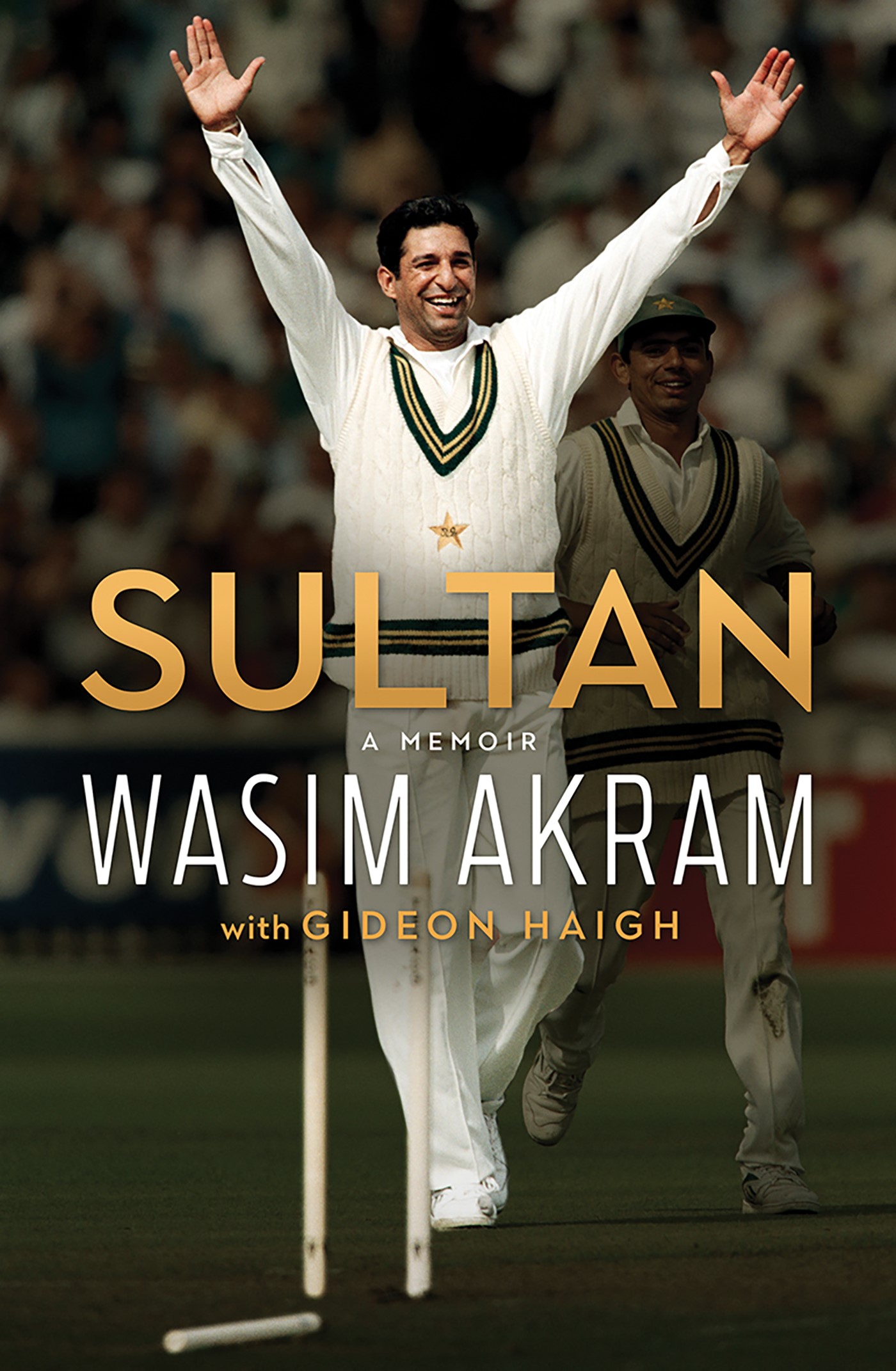

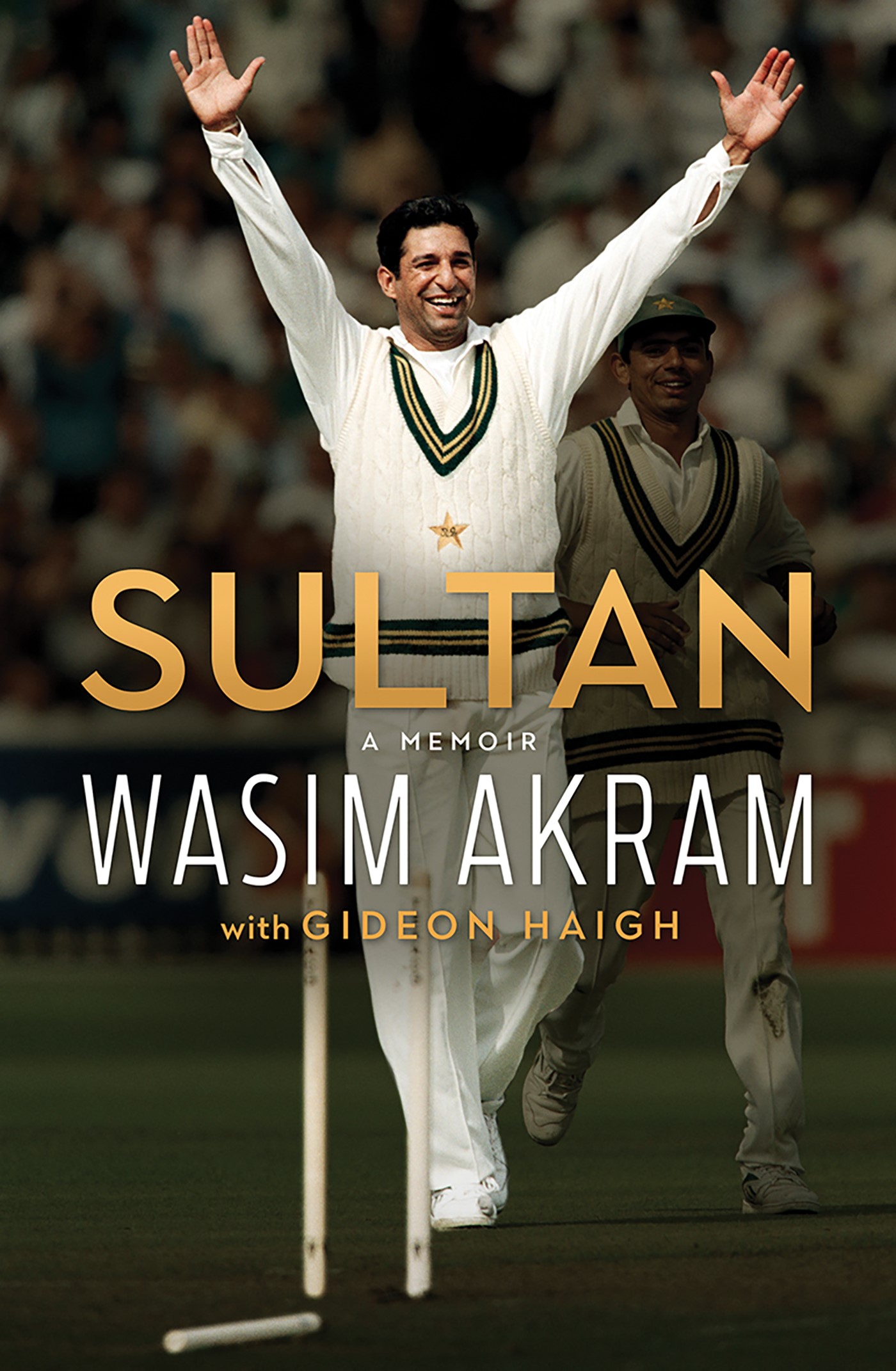

- Book 1 Title: Sultan

- Book 1 Subtitle: A memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Hardie Grant Books, $45 hb, 296 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Well, was he? There’s significance in Birmingham’s pointedness. For all his undisputed on-field greatness, a penumbra of allegation and suspicion has hung round Akram. Was he a match fixer, a ball tamperer, or a fair and principled player, one of the greatest bowlers and bowling all-rounders the game has produced?

These are questions Akram seeks at last to address in Sultan: A memoir, a work co-authored with cricket-writing doyen Gideon Haigh. As Akram writes in the book’s introduction: ‘In all the chaos and controversies I had been a part of ... I had kept my own counsel. I had never been sure what to do, what to say, where to begin ... wasn’t there a case for setting the record straight?’

Which is not to say that this is a book given over to self-defence or long passages of pleading. In the most part it’s a work that modestly details a career of astounding accomplishment. Wasim Akram may have been a master of pace and swing bowling, but it turns out he is also a master of graceful and self-effacing understatement. Here are some examples: ‘The only way I could keep the West Indies from romping away was by taking their last four second-innings wickets in five balls’; ‘We dropped Desmond Haynes from consecutive balls and were unable to take a wicket, although I broke Brian Lara’s foot with a yorker’; ‘I got Graham Gooch straight away, but I struggled until late in the Test when I yorked Jack Russell, had Phil DeFreitas caught at slip and bowled Devon Malcolm in four balls.’

None of this reads like false or forced modesty. The Wasim we find in this memoir is a man quietly confident of his extra-ordinary talent and skill, a combination that plucks him from an urban obscurity that is a rare background in top-flight Pakistani cricket, a place where patronage can be a more certain indicator of future success. ‘I have no such background,’ he writes. ‘I picked cricket up from watching others. The approaching sprint, the fast arms, the back foot pointing to the sightscreen – they just came naturally. I went from the street to the Test team in a couple of years despite having no link to the top and no cricket in my blood.’

The book clips succinctly through a career that begins with his improbable national selection when he was a teenager, followed by the quick realisation of remarkable promise. The support and tutelage of the great Imran Khan is critical; the wickets and the runs flow. We meet the characters of the game – ‘Suddenly Viv seemed to swell in size. “Don’t swear at me man,” he rumbled. “Or I’ll kill you”’ – as the narrative runs almost ball by ball through a solid selection of Wasim’s 147 tests and 280 one-day internationals.

A parallel picture emerges beside this pleasant rattle of runs and balls. Increasingly, we become aware of the politics of power and ego that permeate Pakistani cricket, but that also lurk in other corners of the international game, with their jealousies and even darker forces.

Wasim and Pakistan refine a new skill, benefiting greatly from the developing art of reverse swing, making an old ball swerve to deadly effect. The trick is to keep one hemisphere of the ball scuffed, the other shiny. The wickets flow, but the accusations follow: was ball-tampering involved? Says Wasim: ‘I took the whispering about reverse swing personally. Had Australia or England prospered from a new skill, the cricket world would have stood and applauded. We were seen as sneaky, tricky, deceptive.’ Likewise, the proximity of money, power, and gambling become omnipresent and divisive. Are bookies and bribes twisting results? Nothing is clear, but there is a sense of rot that extends beyond Wasim and his teammates. The likes of Shane Warne and Mark Waugh are mentioned.

There is a quiet skill in the writing that stitches all this together with both rhythm and variety, sometimes giving an economical account of the simple statistics of a match, sometimes zooming in for the human detail, sometimes dwelling on the accumulating drama as matches unfold day by day. Credit may well be due here to co-writer Haigh, because there is an expert touch in these pages that gives narrative flex and lends an engagingly consistent personal tone to what might otherwise have been a number-crunching exercise. The Wasim Akram that emerges is a complex figure, a man who by late career is battling allegations of match fixing that escalate to formal inquiries propelled by the cynical power politics of Pakistani cricket. In the closing pages he also confronts cocaine addiction – a destructive accessory to his fame – and the death of his first wife, Huma Mufti. He reflects too on the imbalance in his life, tipped too much to cricket and too little to family and a long-supressed humility. ‘I was a big name, a big presence. And I had big problems.’

Was he a crim? Wasim’s emphatic answer is no. He was just a star who eventually fell, a little more happily for it, closer to earth.

Comments powered by CComment