- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Bedazzled

- Article Subtitle: Ghastliness between writers

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

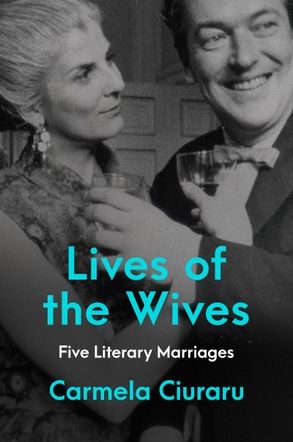

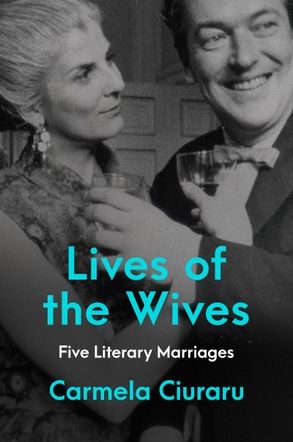

This book has one of the most off-putting jackets of recent memory. Elizabeth Jane Howard, glass in hand, is gazing attentively at her celebrated novelist husband Kingsley Amis, who is beaming with self-congratulatory pleasure at someone out of shot. Howard, no mean writer herself, seems to be performing the good wife’s duty of smiling at a joke she has heard at least ten times. It is a photo that invites the reader to buckle up for five essays about the wives of prominent writers who gave up their own ambitions for the greater good of being ‘handmaidens to genius’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jacqueline Kent reviews 'Lives of the Wives: Five literary marriages' by Carmela Ciuraru

- Book 1 Title: Lives of the Wives

- Book 1 Subtitle: Five literary marriages

- Book 1 Biblio: HarperCollins, $49.99 hb, 324 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Troubridge was a talented painter and linguist who fell intensely in love with Marguerite Antonia Radclyffe, known as Radclyffe Hall and now remembered exclusively for her heartfelt lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness (1928). Hall wrote nine other novels, most of which sold very well at the time. Troubridge did all the grunt work for these: research, typing manuscripts, and editing, as well as running the house while her partner devoted all her time to writing. It was a gruelling life for which she received little thanks from Hall, and Troubridge suffered greatly from jealousy and suppressed anger. (The photograph in this book does not suggest that they had much fun together.) Nevertheless, their relationship endured until death – the only one of the five to do so.

Elsa Morante spent a great deal of angry energy trying not to be known as the wife of Alberto Moravia, a difficult task since, as Ciuraru points out, he was one of the most successful Italian writers of the twentieth century. Morante was a novelist too, but with a literary sensibility very different from her husband’s. His astutely observed and sparely written examinations of sexuality and social alienation lent themselves to acclaimed films such as The Conformist and The Woman of Rome; Morante’s work was altogether knottier and more psychologically engaged. Theirs was a stormy relationship, mostly because of Moravia’s signature detachment and Morante’s determination to develop her own voice. According to Ciuraru, Morante was a nightmare to work with, but even so it’s impossible not to be on her side. Morante is now widely admired as well as being credited as a mentor by Elena Ferrante, among others.

Kenneth Tynan and Elaine Dundy were celebrities whose alcohol and drug-fuelled evisceration of each other could have had Edward Albee taking notes for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? They are probably the most tedious of the couples described here, though it is cheering to report that Dundy gave as good as she got. In a portrait markedly less affectionate than Martin Amis’s in his memoir Experience (2000), Ciuraru presents Kingsley Amis as a dedicated misogynist as well as a faithless drunk, with Elizabeth Jane Howard as little short of heroic in keeping their marriage together. Heroism is also a feature of the marriage of Roald Dahl and Patricia Neal. It is a story that has often been told, comprising illness, dreadful accidents, the death of their eldest child and Neal’s debilitating stroke. Dahl was nobody’s gift as a husband and probably not as a man, but his persistent and intelligent care of his family – including his often bullying efforts to ensure that Neal did not become ‘a vegetable’ – cannot be denied. Ciuraru doesn’t quite know what to make of Dahl, and settles for describing him as ‘complex’, which doesn’t much help.

Lives of the Wives a frustrating book in some ways. What attracted these women to these men? It’s not enough to say that they were all ‘dazzled’. What possibilities did they see for themselves and their partners? What about the question of children (only two couples produced them)? Did these relationships feed into the work these writers produced, and how? Ciuraru’s stories raise intriguing questions, but she skates around most of them. Ciuraru quotes Howard’s comment that ‘It’s true to say all writers are selfish people. All artists are, really. But it’s not quite enough of an excuse’. Yes, and ...?

The marketing department of HarperCollins must have thought this book would be an easy sell, especially for book clubs. It may well be, but short biographical essays are deceptively difficult to bring off. Ciuraru does attempt to show the dynamics of these marriages, but she doesn’t quite manage it. Her writing, though clear, is matter of fact and rather flat, and she depends wholly on published biographies and letters. Because she offers little analysis and few insights of her own, it’s hard to see what this book is trying to do. What message is it giving the reader, apart from saying that if women have literary or artistic ambitions, marriage to a well-known writer is likely to end in tears?

A hardback with back-of-jacket praise from the likes of Francine Prose, Lives of the Wives has the air of serious literary biography. But with its mixture of narrative, gossip and other people’s opinions, it sometimes reads like a series of magazine articles. Though interesting enough, it leaves very little trace behind.

Comments powered by CComment