- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Righteous rage

- Article Subtitle: The Catholic Church’s betrayal of children

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

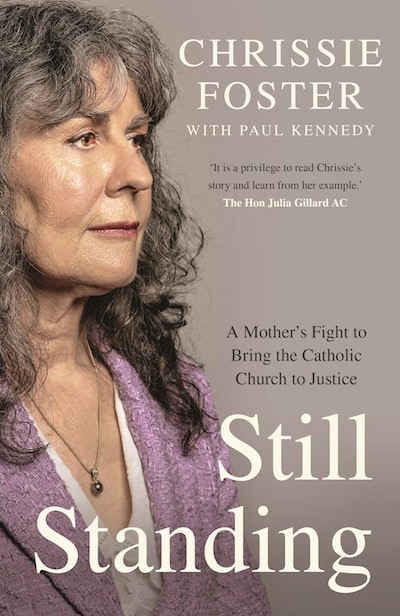

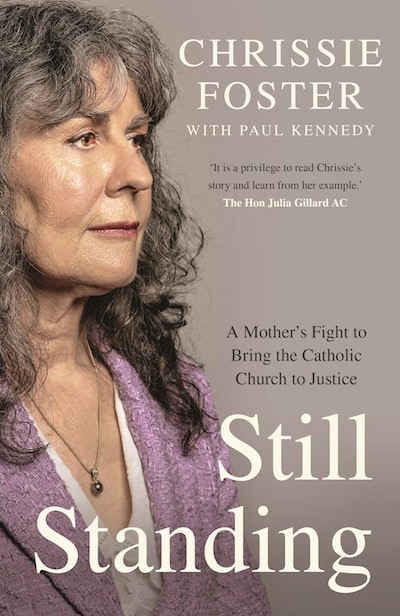

This is a book about rage, as Chrissie Foster says in her opening sentence. It is motivated and driven by rage and, if this is not an oxymoron, it is a panegyric to rage.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Barney Zwartz reviews 'Still Standing' by Chrissie Foster, with Paul Kennedy

- Book 1 Title: Still Standing

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $35 pb, 336 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Nor have I ever forgotten Chrissie’s powerful account in her earlier book – also written with Paul Kennedy, Hell on the Way to Heaven (2011) – of the Fosters’ meeting with Archbishop George Pell in 1997. According to her husband, Anthony, who died in 2017, the future cardinal showed a sociopathic lack of empathy. The Fosters were shown into a cramped furniture storage room in the presbytery and given a small wooden bench for both of them to sit on. The only other seat was a throne-like red leather armchair in which Pell stretched out in a way they found intimidating. He told them that if they didn’t like the $50,000 offer under the church’s Melbourne Response abuse protocol they could take the church to court.

The Fosters did, whereupon the Catholic Church denied the rapes, despite their own investigator having confirmed them. The church settled before judgment for $450,000 for Emma plus more in compensation for Katie. Rage? How on earth could it be otherwise?

Paradoxically, there is something dispassionate about Foster’s fury – it is always contained, her criticism is biting but proportionate, and that restraint adds to the intensity.

Still Standing is a scorching but justified excoriation of the Catholic hierarchy in Rome and Australia with a couple of honourable exceptions – the late George Pell, whose supporters always painted him as an unflinching hero of the fight against abuse, not among them. Some may even have believed that Pell championed victims. In fact, as Pell himself admitted, his top priority was protecting the assets and reputation of the Church (both of which causes he ended up damaging), and he offered victims nothing but pro forma and emotionless expressions of regret. The book is the case for the prosecution, and it is powerful and moving, filled with telling details.

Cardinal George Pell near the Vatican, 2020 (Evandro Inetti/ZUMA Wire/Alamy Live News)

Cardinal George Pell near the Vatican, 2020 (Evandro Inetti/ZUMA Wire/Alamy Live News)

Still Standing is far from the first to do this, but part of its power comes from laying bare the devices by which the Catholic hierarchy concealed abuse, moved offenders to different parishes – where they took advantage of the opportunity to ruin hundreds more lives – failed to report abusers to police, deceived parents, bullied and intimidated victims, insisted upon secrecy upon pain of excommunication (including forced non-disclosure agreements), and limited the payouts they made, as well as their complete betrayal of those who should have been seen as most important – all of which has led to revulsion among the Catholic and mainstream communities. Not for nothing has the abuse scandal been seen as the greatest challenge to the Church since the Reformation.

Time and again, Foster exposes church apologies as self-serving and insincere. As she writes of the cover-up, ‘it was deliberate, calculated and clandestine. It was international.’

Pell said before the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sex Abuse that he objected to Catholics being the only cab on the rank. It is true that child abuse is a crime found in many institutions, but, as the Royal Commission observed, nine out of ten clergy cases reported to them were by Catholic perpetrators.

It found, as Foster cites, that 4,444 people came forward between 1980 and 2015 making child sexual abuse allegations (no one can imagine how many victims did not come forward) to ninety-three Catholic Church authorities relating to more than 1,000 Catholic institutions. The average age of victims was ten-and-a-half years for girls, eleven-and-a-half for boys. The worst diocese, statistically, was Sale in Victoria, where fully fifteen per cent of priests were accused of being perpetrators. In terms of Catholic orders, an incredible forty per cent of Brothers of St John of God were accused, followed by Christian Brothers (22%), Salesians of Don Bosco (21.9%) and Marist Brothers (20.4%).

Much of the book is a narrative of the two hugely effective inquiries, the Victorian parliamentary one and the vastly bigger Royal Commission, and the Fosters’ reaction to the Church’s unfolding disgrace. Foster describes the methods of cover-up: secret archives, the ‘mental reservation’ that allows priests to lie under oath, the doctrine of the pontifical secret, victim blaming, euphemisms, destruction of documents, a multitude of ‘I don’t recalls’, and putting as much blame as possible on the dead. Another sad constant is the callous disdain the Fosters met from so many Australian prelates.

Before the Royal Commission reported, Anthony died in May 2017 of a catastrophic brain injury after a fall at Bunnings, another crippling blow for Chrissie. She writes: ‘Anthony was the most patient, intelligent, compassionate and loving man I had ever met. He was the kindest person in the world. The best. He was everything to me. We had been together for thirty-seven years.’

I am glad Foster acknowledges the role of the press in bringing clergy abuse to public attention, leading to the formal inquiries, then reporting them. When I began reporting on this in 2003 – and I was far from the first or most important – the police, the courts, and politicians didn’t really want to know. It was all too hard, and some had even been part of the cover-up. So the emergence of clergy sexual abuse in public consciousness over the next decade highlights how the media can still be a powerful force for good, though our role pales into insignificance against the courage and determination of survivors themselves and people like the Fosters.

Since the Fosters discovered the appalling secret of what happened to their children, their courage and determination has never flagged. As Chrissie Foster writes, ‘It had to be exposed because nobody should suffer as we and others had – there was no choice but to fight and that is what we did, two timid, ordinary people from the suburbs forced into a life beyond any nightmare. But we were good people, who simply could not allow it to continue. So we acted.’

In 2018 Foster received recognition for fighting the good fight when, with Chief Royal Commissioner Peter McClellan, she won the Australian Human Rights Medal.

Three decades after first taking up the cudgels, she is still furious that the high-ranking clergy who enabled and prolonged the sex crimes ‘of adult holy men against the small bodies of children for an average of 2.2 years each child’ have not been held to account. ‘Justice has not yet been served. How can our criminal law allow the Church hierarchy to just walk away from what it heartlessly orchestrated for decades, for centuries?’

It is the bishops (and bureaucrats) who emerge as the worst villains in this story. What could be more shameful or sad; what could more justly inspire rage?

Comments powered by CComment