- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letters

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Getting to know Oscar

- Article Subtitle: A titan of American musical theatre

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the history of the American musical, Oscar Hammerstein II (1895–1960) presents us with what his Siamese king would have described as a puzzlement. Lacking the sophistication of Cole Porter, the verbal dexterity of Lorenz Hart, and the sly wit of Ira Gershwin, his lyrics, taken out of context, can seem hokey and sentimental. Will he ever be forgiven for The Sound of Music’s ‘lark who is learning to pray’? And yet it is his works, written in collaboration with Richard Rodgers, that are constantly revived rather than the flimsier concoctions of his more favoured contemporaries.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Ian Dickson reviews 'The Letters of Oscar Hammerstein II', edited by Mark Eden Horowitz

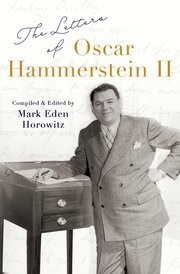

- Book 1 Title: The Letters of Oscar Hammerstein II

- Book 1 Biblio: Oxford University Press, US$39.95 hb, 1,076 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Oscar Hammerstein II was born into a major theatrical family. His grandfather, the opera-obsessed impresario and rumoured lover of Nellie Melba, Oscar Hammerstein I, created a company to rival New York’s Metropolitan Opera; for a while it was so successful that the Met suggested a merger. Both his sons – William, Oscar’s father, and William’s brother Arthur – followed their father into the theatre, Arthur eagerly, William less so. The dying William made his brother promise that he would prevent his son from joining the business, but faced with his nephew’s determination, Arthur surrendered and invited the young man to join his organisation.

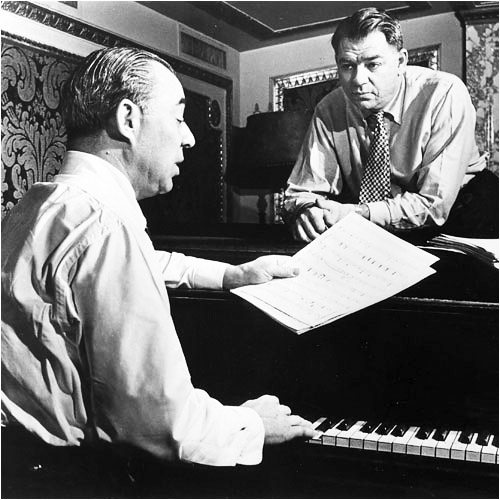

Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein in 1945 (via Wikimedia Commons)

Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein in 1945 (via Wikimedia Commons)

Oscar quickly moved from backstage duties to the creation of musical shows and had a series of successes in collaboration with Vincent Youmans, Rudolf Friml, Sigmund Romberg, and, especially, Jerome Kern, his collaborator on Show Boat (1927) and one of his closest friends.

After his considerable early success, the 1930s proved to be a barren era for Oscar owing to a series of Broadway flops and a frustrating period in Hollywood. By the early 1940s, Oscar was being written off as a has-been. All this changed dramatically when he teamed up with Rodgers, who had finally lost patience with his erratic lyricist, Lorenz Hart. The phenomenal reaction to their work enabled them to set up a company that produced not only their own works but those of others and they became a formidably powerful theatrical operation.

Mark Eden Horowitz’s compilation of the letters of this Titan of the American musical theatre is not for the faint-hearted: it clocks in at 1,076 pages. Horowitz has included letters from Oscar, letters to Oscar, and letters to and from other people entirely. As a compiler, Horowitz is exorbitantly thorough, but perhaps he could have unleashed his editorial blue pencil more rigorously. He delves into the minutiae of Oscar’s life. One letter reads in its entirety ‘Dear Miss Glatterman, Here are the bills. The show looks fine so you can pay them. Best regards, very truly yours, Oscar Hammerstein.’ Do we really need a letter to his brother-in-law thanking him for the gift of a razor that Oscar has no intention of using?

However, if one is willing to wade through the superfluous correspondence, an absorbing picture emerges of Oscar as creator, producer, and man. For anyone interested in the American musical, it is fascinating to watch these famous shows come together. Oscar was prepared to take advice from those he trusted. His frequent collaborator, Josh Logan, had some suggestions for The King and I (1951): ‘May I make a suggestion? Is it possible in the classroom scene ... the children … could be given … a gay, happy dancing song?’ They were – ‘Getting to Know You’.

Oscar was confident enough to handle with panache the negative comments that came his way. Replying to the critic John Crosby who declared that the line ‘and I’m certainly going to tell them’ was the most awkward line he had written, Oscar replied. ‘The merit of the line is, of course, a matter of opinion. You don’t like it and I do. Neither of us can prove the other wrong. I can, however, prove without a shadow of a doubt that it is not the most awkward line I have ever written. I didn’t write it.’

As a public figure, Oscar was always prepared to take a stand for causes he believed in. A fervent anti-racist, he was outraged when he was accused of firing a performer for racist reasons. ‘Any suggestion we took him out of the cast because of his stand on racial intolerance is fantastic, unjust and evil. The play [South Pacific] itself is an argument for racial tolerance … I have no patience with anyone so thoughtless and cruel as to make an assumption like this, entirely against the evidence of my life and work.’ To a correspondent who considered the song ‘You’ve Got to be Taught’ too blatant, he writes: ‘I am most anxious to make the point not only that prejudice exists … but that its birth lies in teaching and not in the fallacious belief that there are basic biological, physiological and mental differences between races.’ With Pearl Buck, he supported an organisation called Welcome House, a refuge for Asian-American orphans, one of whom his daughter Alice adopted.

Oscar became an ardent supporter of United World Federalists, which advocated an expansion of the United Nations to enforce world peace. This admirable if naïve project led to a correspondence with, of all people, General Douglas MacArthur, who by the 1950s appears to have turned into a fervent pacifist.

In person, Oscar could be considered reserved. Apparently, until they reached adulthood, his children found him remote. But the letters he writes to his second wife, the Australian Dorothy Blanchard Hammerstein, show a man of passion: ‘Here I am with my guard down and I confess I can not do anything without you. My soul’s existence depends on you.’

Mark Eden Horowitz’s compilation will surely appeal to American musical completists, but for those who want a straightforward account of Oscar Hammerstein’s life, Hugh Fordin’s splendid biography (Getting to Know Him, 1977) is the book to read.

Comments powered by CComment