- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Composition as calling

- Article Subtitle: A notable activist and musician

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Jillian Graham begins her biography of Margaret Sutherland (1897–1984) with a story that vividly captures two themes that recur throughout the book: Sutherland’s activism, and her sometime exclusion from Australia’s institutional musical life as it developed through her lifetime.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Kay Dreyfus reviews 'Inner Song' by Jillian Graham

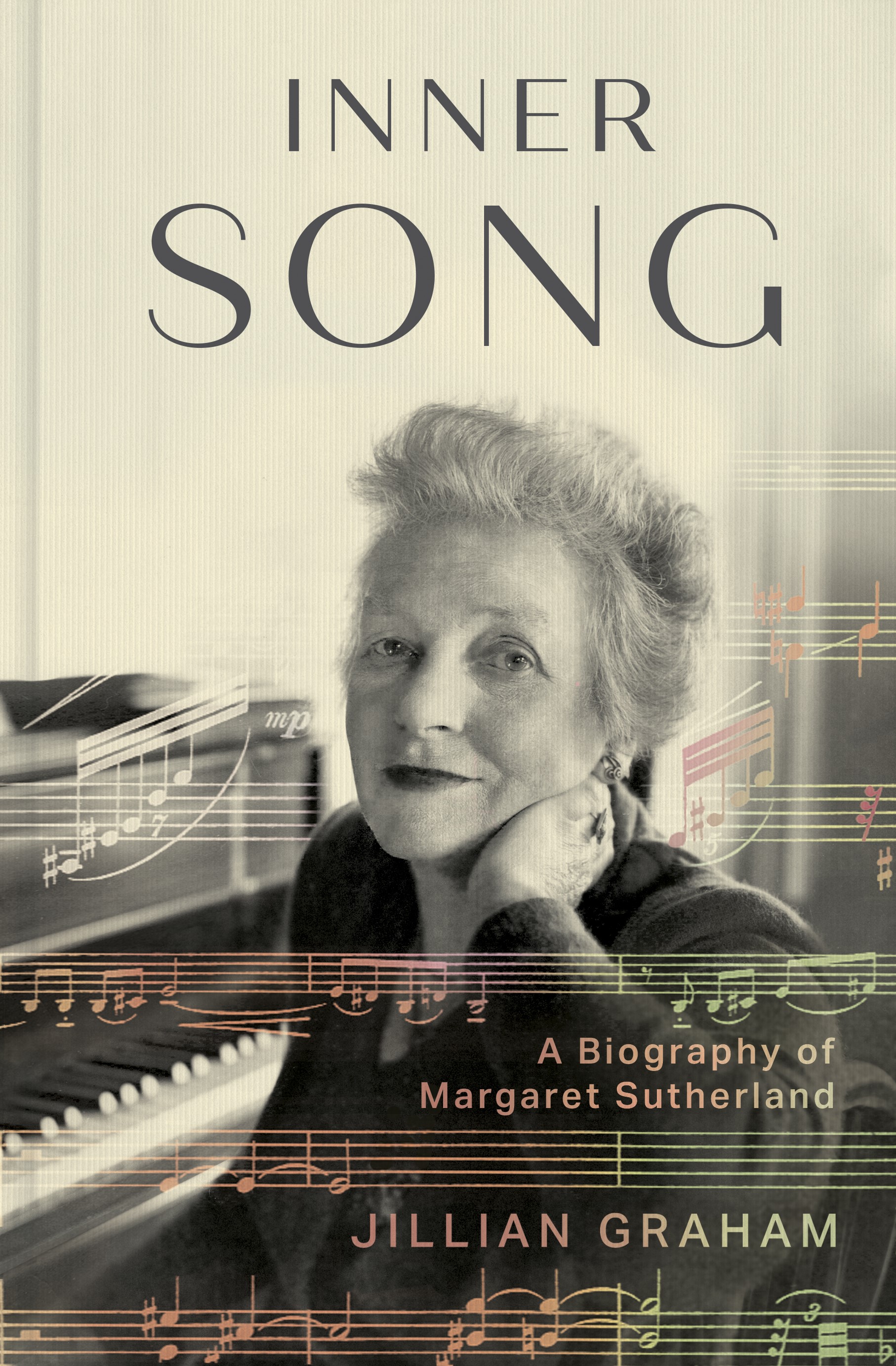

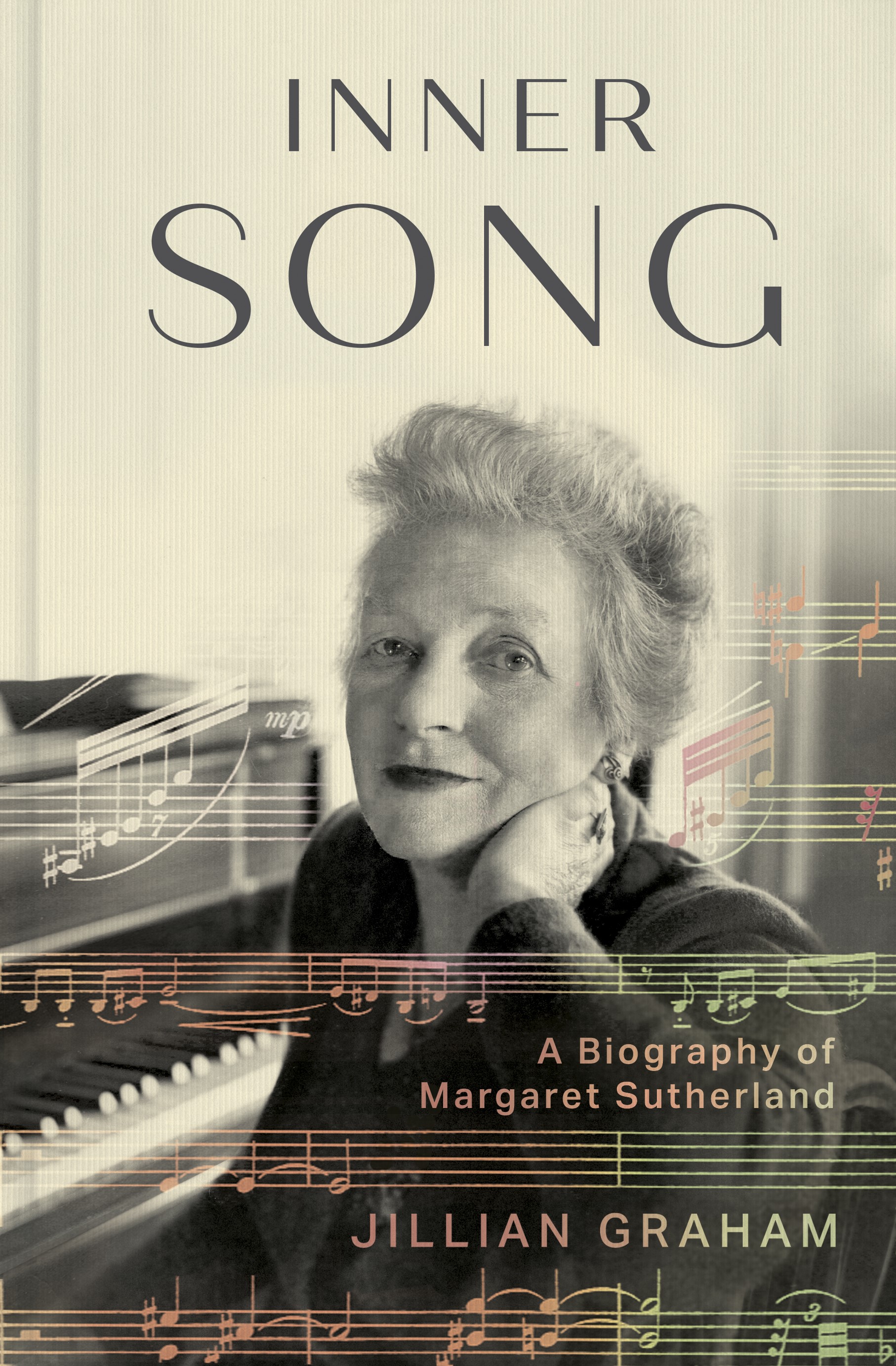

- Book 1 Title: Inner Song

- Book 1 Subtitle: A biography of Margaret Sutherland

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $50 hb, 304 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Joel Crotty is an Australian musicologist with a comprehensive knowledge of twentieth- and twenty-first century Australian music, its practitioners, creators, and scene. I asked him why Margaret Sutherland’s music matters. He opined that Sutherland is ‘the best of her generation’ – that is, the generation of the 1890s to the 1920s – head and shoulders above the rest. She brought Australian composition into the twentieth century, connecting to contemporary Europe, advocating for Béla Bartok and Paul Hindemith against a mainstream preoccupation with the English pastoral style. Sutherland experimented with neoclassicism in the late 1930s and foreshadowed the modernism that was to characterise the music of the 1960s. She wrote in a style that the younger generation of composers wanted, joining them in reacting against the conservatism of the older generation.

Crotty’s good opinion is not without its caveats. Sutherland was at her best in smaller combinations; voice and strings were what she understood best. Works written for larger forces were more problematic. Graham admits that Sutherland did not understand the orchestra or orchestration well; she even wrote outside the range of some instruments. Local musicians tried to help her with her orchestral scores, but at times goodwill evaporated in the face of her combative behaviour and her resistance to the idea of making any changes to her music. Crotty ascribes this deficiency to her lack of formal training.

Among her many strongly held opinions, Sutherland professed a disdain for institutional learning, an attitude which, according to Graham, she had absorbed from her aunts. When she travelled abroad in 1924, she did not enrol in the Royal College of Music, as did a whole cluster of aspiring young Australian women musicians in the 1930s. Instead, though she undertook some private discussions with the English composer Arnold Bax, she preferred to learn by observing the scene, an approach that clearly opened her ears but did not address the technical requirements of writing for a symphony orchestra.

It is probably fair to say that Sutherland was shaped more by her father’s family than by her formal educational experiences, and Graham gives close attention to this formative process as one of the motivations for the biography. The moderately affluent, genteel Sutherland family was certainly remarkable in several ways. The men were all teachers, academics, or professionals who shared with their father a lamentable habit of dying in early middle age; three of the four have entries in the Australian Dictionary of Biography. Of the three women, Jane was an artist while the two other aunts were musicians. Only three of the men married, including Margaret’s father, George. Curiously reclusive, the five unmarried aunts and uncles continued to live together with their widowed mother.

Graham’s narrative of Sutherland’s early years draws generously on Sutherland’s own writings. Apart from a travel diary from an overseas trip in 1951, Sutherland did not keep a diary or journal. But she did write, and well; Graham quotes freely from her autobiographical notes and articles, from talks given to the various clubs and societies of which she was a member, from newspaper opinion pieces and correspondence. Accordingly, Sutherland’s own voice comes through strongly. The primary parental influence was her father; in the classification system devised by the German pop-psychologist Volker Elis Pilgrim, she was a father–daughter. Graham remarks that she rarely mentions her mother, except to say that she was a ‘wonderful mother’. The aunts were stronger role models. Her aunt Julia was Margaret’s first piano teacher, while she derived the idea that her composing was a calling from her aunt Jane.

All is charm in Margaret’s stories of her early life and her Sutherland family. Later, the tone changes. Her exchanges with the newly established Australian Broadcasting Commission are argumentative and challenging, though one might say alongside batting for her own music she was also advocating for Australian music generally – self-interest and selflessness are sometimes hard to disentangle from her lifelong, energetic campaigning. But it is her account of her undoubtedly troubled marriage to Norman Albiston that is most disturbing. It was clearly a mismatch; it may well be, given her family’s history with the institution, that Margaret was temperamentally unsuited to marriage. She certainly seems to have been more comfortable with the company of other professional women, and it is striking that most of the people Graham interviewed for her book are women.

Part of the received narrative of Sutherland’s life is that her marriage was unhappy (which it clearly was) and that her husband was unsympathetic to her creative aspirations. But I could not help noticing that in the ten-roomed house the couple acquired in Kew, there was a dedicated music room large enough to house two pianos, one at least a grand, and that Margaret kept the house after the divorce. Graham admits that we are given a completely one-sided view of the ‘hideous years’ of the marriage. Quoting Norman’s third wife, to whom he was married for twenty-eight years, Graham offers a more sympathetic portrait of the man.

Altogether, Graham’s biography is a balanced and tender study of a complex life, the third of three dedicated studies of the life and works of this important Australian musician.

Comments powered by CComment