- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Change as possible

- Article Subtitle: An admirably ambitious début

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Susan Paterson’s first novel, Where Light Meets Water, offers readers the various pleasures of the traditional Bildungsroman. Spanning the years 1847 to 1871, it centres on the life of Thomas Rutherford, a man torn between devotion to his work as a mariner and an abiding passion for painting seascapes. The predominant use of an omniscient narrator provides unfettered access to his conflicted inner life and, less frequently, to that of his spirited wife Catherine. The vivid depiction of a host of global settings, including London, the markets of Calcutta, Melbourne during the gold rush, and an increasingly prosperous Dunedin, adds to the effect of a densely particularised and amplified world. Immersive and absorbing, the novel is a triumph of the old-fashioned art of verisimilitude.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Susan Midalia reviews 'Where Light Meets Water' by Susan Paterson

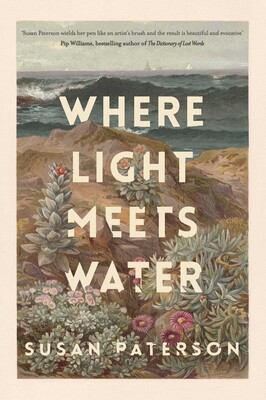

- Book 1 Title: Where Light Meets Water

- Book 1 Biblio: Simon & Schuster, $32.99 pb, 400 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

In its concern with the possibility of change, the novel rewards Tom’s loyalty, honesty, and capacity for hard work. It is also alert to the role of chance in advancing the fortunes of individuals. Catherine, for example, is lucky to have a wealthy father who allows her to marry a working-class man with few material prospects. This plot device feels justified by the subtle analysis of the father’s character and past. Elsewhere, the use of good luck feels overly contrived; the transformation of a starving orphan reads like a Dickensian fairy tale, as well as an obvious symbolic substitution for Tom’s earlier and grievous loss. Still, in the wider social sphere, the novel understands that change is not necessarily progressive. It shows how, in the wake of the Industrial Revolution, people in London were degraded by poverty, prostitution, and homelessness. The Crystal Palace Exhibition is seen by Tom both as a marvel of technological inventiveness and an erasure of the exploited human labour that made the marvel possible. Tom’s more expansive vision of the world will later extend to his travels in Australia, where he will witness the power of empire that reminds a ‘blackfellow’ of his place ‘by the pull of a righteous trigger’. Such details of history, as well as Paterson’s extensive research into life at sea and developments in painterly techniques, are skilfully integrated into the narrative, such that they read like the characters’ lived experience of physical work and their commitment to the life of art.

Change is also evident in the novel’s anticipation of the modernist valorisation of art as an enduring source of meaning. Art is represented as a form of self-expression, particularly for silenced women; as Catherine pointedly observes: ‘You pick up the brush to hear the sound of your voice.’ Art also offers the gift of connection, its most poignant example the miniature paintings Tom sends across oceans to his young son. Art is social rebellion, evident in the non-representational paintings of William Turner, himself the son of a lowly butcher. Art is emphasised as a mode of perception that resists the drive to power, as in Tom’s awestruck recreation of the natural world, or his delicate images of Catherine: ‘he followed the pale line of her neck … the shift of [her] collarbones like driftwood under cool white sand’. His descriptions of marital sex are decidedly un-Victorian by the mere fact of their inclusion, and are presented with a delightful playfulness and tenderness, as well as a deftly rendered erotic charge. Even more politically radical is the representation of Catherine as a sexually active woman instead of the typically compliant, if not terrified, object of masculine desire.

Change in the novel is also a matter of form. It is registered in the shift at the end from omniscience to Tom’s first-person narration, which signals the modernist insistence on the perspectival nature of reality. The prose style is a blend of the moral abstractions of nineteenth-century literature and the metaphoric, evocative prose of modernist writers. There is also a prefiguring of Virginia Woolf’s androgynous vision in the mutually enriching exchange of ideas about painting between Tom and Catherine, and in Catherine’s avowed rejection of distinctively male and female forms of art.

While painting as an art form dominates the novel, the value of story is given its due. Tom’s past is offered to Catherine in extensive passages that reveal his knowledge of and passion for the sea. A modern-day Othello, he makes himself known to his beloved by speaking of the dangers he has passed. But while the novel believes in the power of storytelling to bridge the class divide, it also understands the melancholy consequences of silence. Tom is unable to speak to anyone about either the death of his parents or his guilt as a husband and father. One of the novel’s most affecting aspects is the persistence in his mind and heart of absence: of loved ones, and the deep connection he craves with others.

Although it loses momentum in the final stages, Where Light Meets Water is a great pleasure to read. Visually sumptuous, beautifully written and often deeply moving, the novel combines psychological complexity and the sweep of history to create an admirably ambitious début.

Comments powered by CComment