- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Autumnal rustling

- Article Subtitle: Margaret Atwood’s new short story collection

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Margaret Atwood is fond of repeating the adage that creative writing is ‘10 percent inspiration and 90 percent perspiration’. The same can be said of reading Atwood’s latest story collection, Old Babes in the Wood. When a writer is so venerated, there is a risk of both authorial and editorial complacency. The book’s back cover features this excerpt: ‘My heart is broken, Nell thinks. But in our family we don’t say, “My heart is broken.” We say, “Are there any cookies?”’ This reminded me of one of those film trailers where you wonder: if these gags made the promo, how bland is the rest? If a story collection is like a box of cookies, I’m afraid these are mostly half-baked (if not a little stale and crumbly).

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Sascha Morrell reviews 'Old Babes in the Wood: Stories' by Margaret Atwood

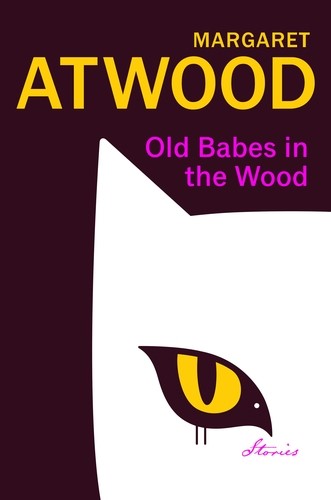

- Book 1 Title: Old Babes in the Wood

- Book 1 Subtitle: Stories

- Book 1 Biblio: Chatto & Windus, $45 hb, 257 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

For better and for worse, we come at Nell’s primary loss through how she grapples with other (and others’) losses. In the inauspiciously titled ‘Morte de Smudgie’, the widowed Nell manages her grief at the loss of her cat ‘by rewriting Tennyson’s “Morte d’Arthur,” with Smudgie in the leading role’. The premise feels like a thin excuse for Atwood to showcase her own efforts on this front (think feline mourners raising a ‘caterwaul’ for their leader who ‘shot thro’ the flowers at Catelot, and charged / Before the eyes of pusses and toms’). Atwood pulls the same trick in ‘A Dusty Lunch’, with Nell poring over poems by Tig’s World War II-brigadier father (but actually by Atwood).

The ‘My Evil Mother’ stories are an uneven batch in both quality and theme. If you are a sceptic as regards Atwood’s standing as ‘the reigning queen of speculative fiction’, her efforts here will not convert you. In the Covid-inspired ‘Impatient Griselda’, an alien tasked with entertaining quarantined earthlings during a plague retells the story of the faithful wife Griselda from Boccaccio’s Decameron, minus the wifely obedience. It’s a dramatic monologue, full of implied stage directions, but the results are clunky and sophomoric, with lines like ‘What is WTF? Sorry, I don’t understand’ and ‘Now I’ll just ooze out under the door. It is so useful not to have a skeleton.’ I could feel the genre-writing workshop prompt: ‘Write a story about pandemic lockdown from the point of view of an alien.’ For that matter, Atwood is repeating herself: she already used the device of a faux-naïve alien educating humans in ‘Greetings, Earthlings! What are these Human Rights of Which You Speak?’, collected in her last book Burning Questions (2022).

In ‘Metempsychosis’, the narrator’s soul ‘jump[s] directly from snail to human’ and begins ‘space-sharing’ with a banking call-centre worker named Amber. Atwood’s efforts to create the snail’s sensorium are half-hearted, and the numerous points where her snail-narrator breaks character indicate that we should not take the thought experiment too seriously (one of its first observations upon entering Amber’s lifeworld is that ‘the bank’s anti-hacking defences were crap’). It may be, the narrator admits, that Amber is having a ‘psychotic break’. Or, Atwood suggests in publicity for the book, perhaps the story is really about ‘being quite old’? But reread with these ideas in mind, the piece does not improve.

Atwood’s freewheeling messing-up of her ostensible premises would be forgivable if the results were more consistently witty, engaging, and insightful, but it seems like an easy out. You sense an author a bit too fascinated by her every whim.

The collection’s weakest piece is ‘The Dead Interview’, an imagined conversation in radio-playscript style between a fictionalised Atwood and the dead George Orwell, conducted through a spiritual medium. ‘It’s such an honour to encounter you. You’ve been a huge influence on my own work!’ the Atwood character enthuses at the outset. She lets Orwell off lightly for his infamous misogyny, leaving unchallenged his excuse – ‘I was a man of my time. One can hardly be otherwise’ – in order to get back to her fangirl routine.

Among the things Orwell got right, Atwood updates him, is that ‘the United States came very close to a coup d’etat, just recently. Invasion of the Capitol. Attempt to overturn the election results.’ To which Orwell responds, ‘Sounds familiar. I lived in an age of coups, of one kind or another. Different slogans, but same idea.’ Lest we think this lazy, uninspired writing, Atwood’s Orwell steps in to admire Atwood’s own way with words. Meanwhile, the female medium is a mere device, whose questions when the connection is lost – ‘Did your friend show up? […] Have a good chat, did you? Cup of tea? Anything wrong, dear?’ – bring the piece to its cheesy close.

Atwood is a writer of irrepressible energy and eclectic interests (references to the Victorian era and World War II mingle with molluscs and slime-mould in her depictions of ageing and death). The many testaments to her powers include not only literary awards but multiple peace prizes. She has earned the right to lounge a bit on her bed of laurels, and her devoted fans will enjoy their autumnal rustling. Others may find themselves reaching for the leaf-blower.

Comments powered by CComment