- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Lust for liberation

- Article Subtitle: Gough Whitlam’s reformist vision

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

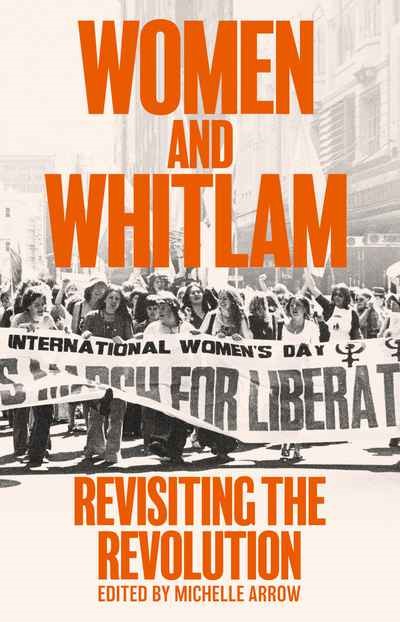

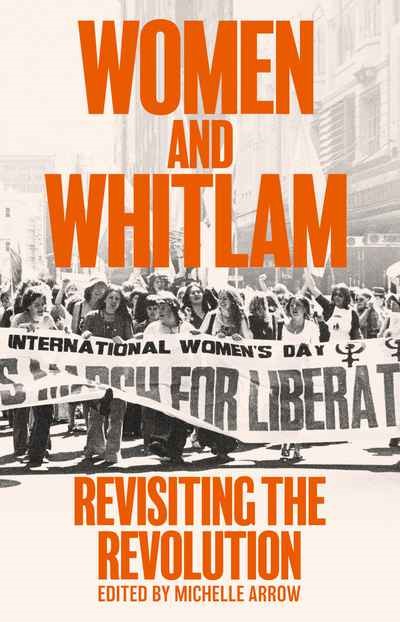

When the Whitlam government was elected in 1972, women across Australia responded with elation. The Women’s Liberation Movement had helped bring Labor to power and was in turn galvanised by the programs, reforms, and appointments that began to be put in place. In Women and Whitlam: Revisiting the revolution, Michelle Arrow has assembled a splendid range of memoirs, reminiscences, and short essays that document twenty-five women’s perspectives on this much mythologised era. The collection will be of great interest to those who lived through these momentous times and to readers of Australian social and political history more generally. It will also serve as a useful teaching text.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Marilyn Lake reviews 'Women and Whitlam: Revisiting the revolution', edited by Michelle Arrow

- Book 1 Title: Women and Whitlam

- Book 1 Subtitle: Revisiting the revolution

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $34.99 pb, 352 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The appointment of Reid as Superfem, which is how she was characterised in a contemporary Refractory Girl cartoon, inevitably attracted criticism from some sectors of the women’s movement, but it was a move that also generated high expectations. In her chapter on ‘Whitlam and the Women’s Liberation Movement’, Reid highlights the role of ideas and theoretical discussion in women’s liberation meetings, debates about how best to achieve radical social transformation.

Impassioned discussions took place all over the country about ‘reform versus revolution, about wages for housewives, about radical lesbianism and a separatist movement, about the nature of sisterhood, about the landscape of patriarchy, of misogyny, of sexism’. The latter was a new word (coined initially by American literary theorist Kate Millett in Sexual Politics), necessary to engage in the new social and political analysis. Women’s liberationists also promulgated a different set of meeting practices – sisterhood, the importance of listening to other women, consciousness-raising, the avoidance of hierarchies – and an ethics of solidarity.

Reid took on an impossible workload. In the months after her appointment, she travelled around Australia to find out what women wanted. ‘The women who spoke out came from all backgrounds: migrant, Indigenous, rural, elderly, suburban, working, single, wealthy, married. We talked in factories, in housing estates, on farms, in schools, at women’s meetings, in dairies, in jails, in universities – in short wherever women were.’ She also received thousands of letters – more letters than any member of Cabinet other than the prime minister. At the same time, Reid embarked on ‘the long march into the halls and offices of Parliament and the bureaucracy to learn how to formulate, seek approval for and implement the emerging policies’.

Policies were being formulated to address a range of issues – contraception, childcare, equal pay, equal opportunity, discrimination, divorce, and single mothers. In her introduction, Arrow points to some of the policy achievements: the Whitlam government re-opened the equal pay case; extended the minimum wage for women; improved the accessibility of contraception; funded women’s refuges and health centres; funded community childcare; introduced accessible, no-fault divorce and the Family Court; introduced paid maternity leave in the public service; and investigated structural discrimination against girls in schools. Arrow could have added to the list the abolition of university fees, which, as Sarah Dowse points out, had a truly transformative effect. The policy applied to men and women, but it had a particular impact on women who cared for families, allowing many ‘mature-aged students’ to return to education. Relatedly, the introduction of a supporting mother’s benefit for single women was also transformational.

For a government that came to power without a formal women’s policy, as Arrow remarks, this is an extraordinary list of achievements. It seems all the more striking given that there were no women in the House of Representatives and no women in the Whitlam government. Where did the changes come from? Policy demands had been formulated by the women’s liberation movement and women in myriad civil society organisations. They were developed by feminists newly recruited to the bureaucracy, who had years of experience in policy development, often at the state level.

Take the case of Marie Coleman, who had worked for the Victorian Council of Social Service in Victoria, and was appointed by Whitlam in March 1973 to head up the Social Welfare Commission, the most senior appointment ever of a woman in the federal public service. In her chapter on ‘Women’s Health, Women’s Welfare’, Coleman points out that much of the Whitlam government program ‘derived from and built on the policy ideas being developed prior to its election in universities, the community sector, the health sector and beyond’.

Coleman, like many of the other contributors, stresses the importance of the women’s movement in driving changes – in childcare, women’s health and services such as women’s refuges – but also in culture, education, publishing, and history-making. Similarly, Terese Edwards, in her chapter ‘Out of Wedlock, Out of Luck’, documents the activism of the women who formed the Council of the Single Mother and Her Child in Melbourne in 1969, and lobbied hard against the expectation that unmarried mothers should give up their children for adoption. Once the Whitlam government was elected, she notes, reform was achieved quickly. They were heady times.

Bill Hayden, as Minister for Social Security, introduced the Bill to establish the Supporting Mother’s Benefit in 1973. It challenged religious institutions and moral conservatives, writes Edwards, though she seems unaware of the precedent of the Maternity Allowance Act introduced by a Labor government in 1912, which also extended payments to unmarried mothers, outraging many conservatives. This earlier radical innovation was a response by Prime Minister Andrew Fisher to enfranchised Labor women’s mobilisations in the first decade of the twentieth century.

In her introduction, Arrow writes that for much of the twentieth century women had not been encouraged to take active roles in politics, but she seems to equate an active role in politics with election to parliament and the pursuit of a political career. This collection itself is testament to the power and impact of women’s mobilisations in civil society, documenting women’s astonishing history of activism in so many fields other than parliamentary politics.

Many of the contributors note the absence of women in the Whitlam government and indeed in the House of Representatives. The striking paradox presented by this valuable collection is that women were able to achieve a policy revolution in the complete absence of women politicians. What did prove necessary was a strong and well-informed political leader, responsive to and unthreatened by a determined and demanding grassroots women’s movement. The election of women to parliament would be necessary to achieve democratic political representation, but not for the enactment of radical social, economic, and legal change that would improve the lives of all women.

Comments powered by CComment