- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letters

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Letters to the Editor

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Read this issue's Letters to the Editor. Want to write a letter to ABR? Send one to us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

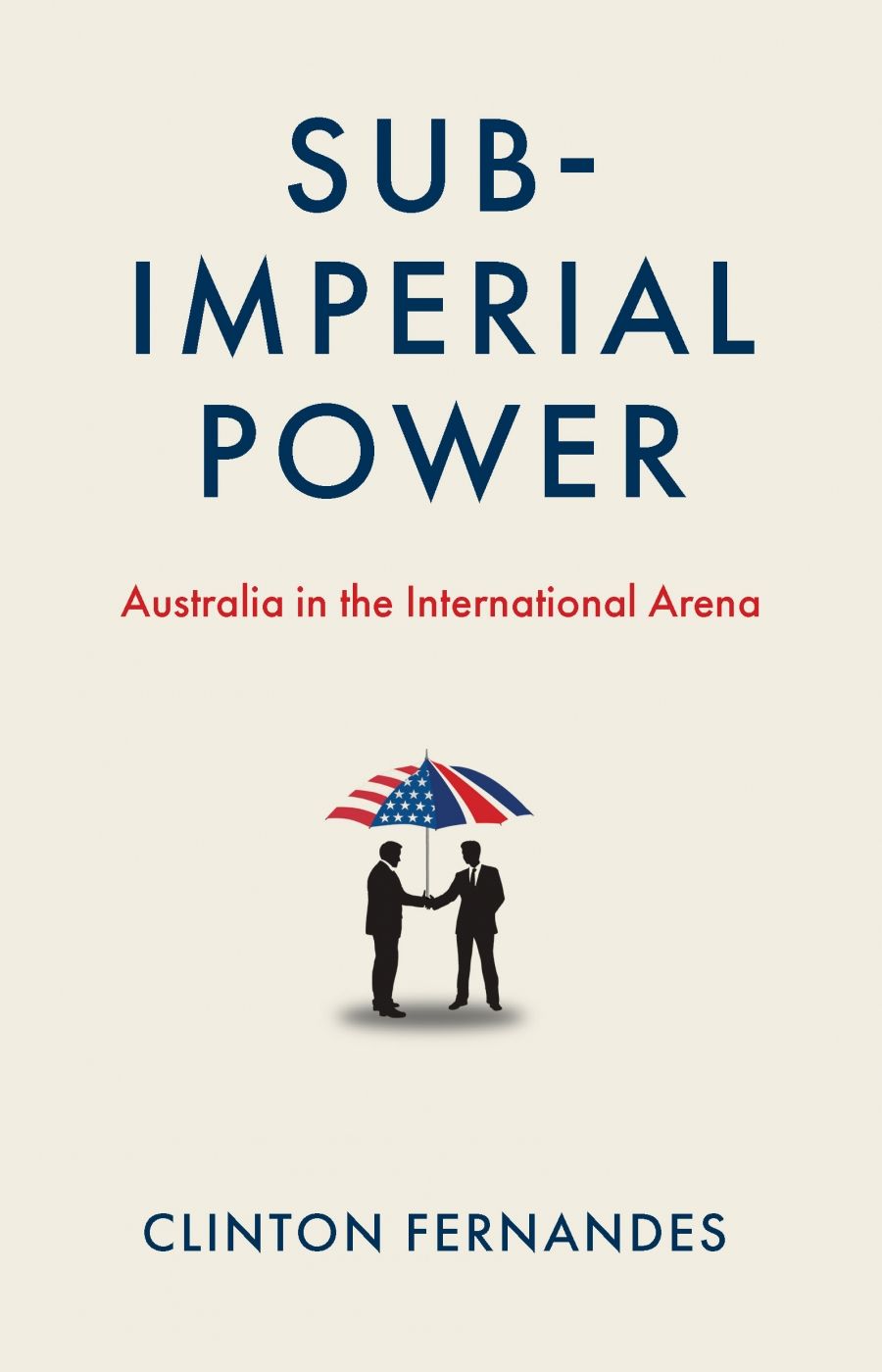

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Letters to the Editor

![]() Want to write a letter to ABR? Send one to us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Want to write a letter to ABR? Send one to us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Questions of character

Dear Editor,

Thanks to Penny Russell for her kind and insightful review of my book Elizabeth and John (ABR, November 2022). She raises one particularly interesting question, summed up by her statement, referring to conventional judgements of John Macarthur: ‘his personal shortcomings are exacerbated by what he represents’. That’s to say, he is usually judged as one of the lead characters in the original invasion of New South Wales.

There are several important issues embedded in this statement. First of all, it implies very clearly that books such as this are bound to offer moral judgements on the past. That is certainly true. It also implies that historical actors are to be judged for their lives as a whole. That might be a matter of opinion, but if so then there is another question. In making such judgements, must we also take account of what he or she represents?

In the book, I have tried to draw a clear line between questions of personal character and questions of representation. The effort is there in every chapter. Both matter, but from the point of view of history-writing – not to say the assessment of human character in any circumstances – I can’t think of anything more important.

One of the leading characters in the book, the lawyer Saxe Bannister, in his own efforts to give a new moral basis to relations between invaders and invaded, spoke about the need for ‘justice at every step’. That’s also the aim of this book.

In his History of Australia, Manning Clark took it for granted that, even in the narrow world of colonial Australia, certain men and women might be remembered today as figures of high tragedy. History is literature – it is an exploration of humanity – and that means both remembering and forgetting what they represent. Starting with that ambivalence can take the history of the invasion period in new directions altogether, as I have tried to show.

I have also been inspired by fictional writing (obviously), including historical fiction. Take the late Hilary Mantel’s three-volume narrative of the life of Henry VIII’s minister Thomas Cromwell (Wolf Hall, Bring up the Bodies, and The Mirror and the Light). Mantel not only draws brilliant portraits. She also says, or implies, something wonderfully enlightening about the cultural relativity of violence. It’s clear from her writing that making individuals in some sense representative of their time is crucial to good portraiture. Not only the portraits but also the context provided for them are more telling as a result.

In some sense, Elizabeth and John has been an attempt to combine Hilary Mantel’s methods with, say, George Eliot’s (in Middlemarch, etc.) – shooting at the moon, of course, but certainly, for me, worth the effort.

Penny Russell replies:

Many thanks to Alan Atkinson for this response to my review of Elizabeth and John. Alan seeks to understand individuals in the context of their time, and as representative of it. Elizabeth and John offers a sympathetic rendition of the Macarthurs’ thinking and an exemplary portrait of the assumptions and world view that guided their pragmatic and ethical choices. But historians – even historical biographers – are not concerned only with human character. They study ideas in action, and actions have effects, intended and unintended. No individual’s moral reasoning or self-justification could be expected to address the far-reaching, unimagined effects of their everyday actions. The historian, armed with the benefit of hindsight, should at least try. Character and representation matter, but so does historical agency.

John Howard and inequality

Dear Editor,

Professor James Walter has produced a generous, thoughtful, and balanced review of my new book Dreamers and Schemers: A political history of Australia (ABR, November 2022). I lap up the praise and quibble with the criticisms in the usual manner of authors, especially when both come from a scholar on whose large body of stimulating research and ideas the book draws. But I should correct the suggestion that I made the ‘bald assertion’ that ‘[John] Howard was committed to increasing inequality’. The actual quotation did have a little hair, and was also slightly more nuanced: ‘Schools would soon need to have a pole on which to fly the national flag if they did not want to be financially penalised. Such stunts provided the theatrical side of a government that was committed, in its more substantial policy making, to the steady increase of inequality.’ While only delivered in passing, it is a judgement that, I think, bears scrutiny.

Frank Bongiorno, Scullin, ACT

Handsome Harold

Dear Editor,

As usual, James Walter, in his survey of Ross Walker’s book Harold Holt: Always one step further, has written a careful and insightful review (ABR, October 2022). But I wonder about the suggestion that Robert Menzies and Harold Holt were too willing to follow US policy in Vietnam. My memory of Australia’s role in the Vietnam War is that the Liberal government actively encouraged the Johnson administration to escalate. As Menzies famously proclaimed, he saw the war as ‘a thrust by Communist China between the Indian and Pacific Oceans’.

This may only be a difference in emphasis, but given the eerie resemblance to current political rhetoric it seems important to make the point. The Morrison government seemed to echo its 1960s predecessors in its enthusiasm for encouraging conflict between the United States and China.

Dennis Altman, Clifton Hill, Vic.

James Walter replies:

It is certainly true that, in relation to the Vietnam War and the US alliance, Robert Menzies and his successors (including Harold Holt) were seeking ‘a way into’ the diplomatic dialogue and military commitment to Vietnam being considered by the United States after the French rout at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. They were exceedingly concerned about the wider potential for communist aggression, and sought, through ANZUS and SEATO, to achieve something in the Asia Pacific like the defence umbrella offered by NATO in Europe.

There is arguably some resemblance between subsequent attempts, especially by Menzies, to secure the US alliance and the Morrison government’s ratcheting up of the China threat and effort to insinuate itself into partnership with Britain and the United States through AUKUS. But, while intent on winning ‘great and powerful friends’, Menzies’ and Holt’s senior colleagues and officials – Percy Spender, Richard Casey, Garfield Barwick, Arthur Tange, and Paul Hasluck – advocated caution about the dangers of hewing too closely to the American line, and only gradually reached the conclusion that engagement in the conflict (on American terms) was inevitable.

There are fine biographies of each of these major players, and the Cabinet documents on which the biographers draw are usefully assembled in Peter Edwards’s Crises and Commitments (1992) and David Lowe’s Menzies and the ‘Great World Struggle’ (1999). Such research persuades me that Menzies and Holt were too willing to follow US policy, but I remain unpersuaded that they encouraged Lyndon Johnson to escalate.

Unconditional refusal

Dear Editor,

Your compelling review of Shannon Burns’s memoir Childhood highlights not only the graphic story of a traumatic and abusive childhood but also how, as an adult, Burns has unceasingly put himself together again and again, each time as if for the first time (ABR, October 2022). We learn how trauma haunts Burns’s conscious and unconscious mind and also remains in his body, in each of the senses, ready to resurface whenever something triggers a reliving of the traumatic events. How could he have known that too often the worst – the unimaginably painful aftermath of his abusive childhood – was yet to follow, as when he admits to having felt, in his undergraduate years, ‘a murderous impulse on listening to his polished classmates’. Then he admits that even as an adult he ‘still fears his mother more than anyone or anything’.

Your review highlights a deeply revealing story not only about the long-term effects of childhood abuse but also the lasting power and influence of narrative – narrative that helps people like the stoic Shannon Burns to cope, find rewards, and rebuild their lives.

Roger Rees, Goolwa, SA

Time’s wing’d chariot

Dear Editor,

Has Geordie Williamson confused his poets? Surely ‘Time’s wing’d (sic) chariot hurrying near’ is from Andrew Marvell’s poem ‘To His Coy Mistress’? George Herbert might have been pleased with the phrase, though.

Jeffrey Sheather, Dulwich Hill, NSW

Gail Jones

Dear Editor,

It is a paradox that fine fiction is a mode of truth-telling and Gail Jones’s novel Salonika Burning well justifies ‘taking liberties’ with historical fact. Once again she uses her art to bear witness. Diane Stubbings’s review astutely redirects attention to Jones’s interest in ‘the processes by which “truth” is composed’ and the diversely personal nature of perceived truth (ABR, November 2022). Jones exposes the cost of words and actions, the ‘pretty lies’ and fragility of characters tenaciously striving to sustain life amid the futile and relentless hell-on-earth of war. Within the novel, Jones’s conscripts and volunteers tend mercilessly recycled soldiers in a state of exhaustion beyond words, but even at this outpost of humanity, language may save or destroy. Stubbings’s review highlights the courage, tact, and ‘elegance’ of Gail Jones’s latest novel.

Lyn Jacobs, Aldgate, South Australia

Emilia and Shakespeare

Dear Editor,

Diane Stubbings’s review of the play Emilia suggests that ‘the extensive and spurious use of Shakespeare’s words ... might be read as the suppression of Emilia Bassano’s voice’ (ABR Arts, November). If interested in the proof supporting the playwright’s presumption, consider reading my recent book, Aemilia Lanyer as Shakespeare’s Co-Author (Routledge, 2022). Stubbings insightfully asks ‘whether Emilia was a religious poet in the style of John Milton’. There is tantalising evidence in Milton’s first Italian sonnet that the older Emilia was Milton’s teacher (Edward LeComte, Milton Quarterly, 1984).

Mark Bradbeer, online comment