- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Media

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Bollocks really’

- Article Subtitle: The BBC at the crossroads

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This year, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) celebrates its centenary as the world’s largest and oldest broadcasting institution (the US company NBC was founded four years later, in 1926). Whether it will reach its bicentenary, or even have another ten years of life in anything like its current form is a question facing other British institutions such as the Conservative Party, the monarchy, and indeed the Union of England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland itself. Placing the BBC among this group signals its estimable role in defining an imagined community but also the possibility that the existence of these other entities and their function in this process might be finite, subject to challenges from their own internal contradictions as much as from hostile external forces without.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Paul Long reviews two books on the history of the BBC

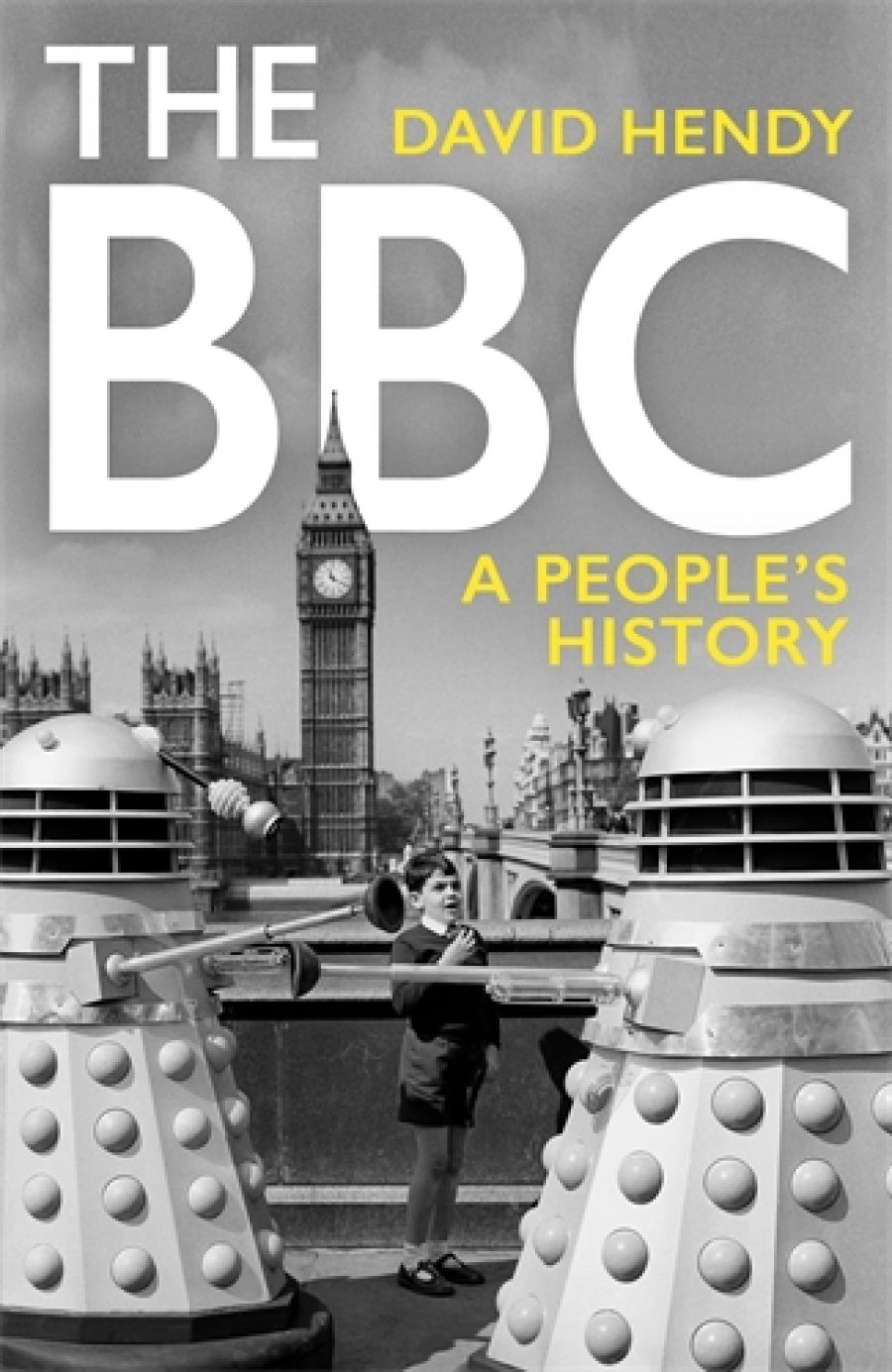

- Book 1 Title: The BBC

- Book 1 Subtitle: A people's history

- Book 1 Biblio: Profile Books, $49.99 hb, 655 pp

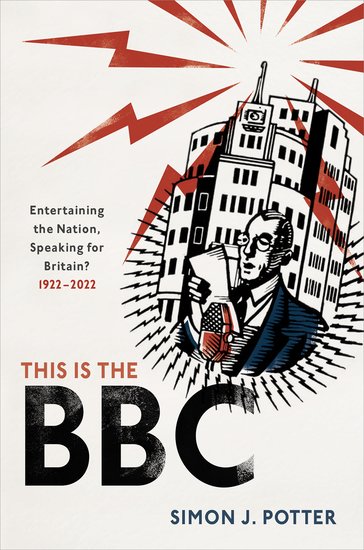

- Book 2 Title: This Is The BBC

- Book 2 Subtitle: Entertaining the nation, speaking for Britain, 1922–2022

- Book 2 Biblio: Oxford University Press, £20 hb, 320 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Consequently, Potter is rather more strident in his coverage and organisation, with conclusions across each chapter, though not unwelcome, giving an air of the textbook. Hendy has space to dig deeper into incident and personality, taking a more self-conscious and writerly approach. He seeks to bring us close to the BBC through the prism of a ‘people’s history’, his aim to portray the women and men who have ‘handcrafted’ the BBC. While not entirely humanising the organisation, this has the effect of countering unhelpful caricatures, whether a ‘po-faced, hectoring “Auntie”’ or the idea of ‘formulaic and machine-tooled’ programming. Through this method, a remarkable cast is brought vividly to life, including shaping founders like John Reith (General Manager), Arthur Burrows (Director of Programs), and Cecil Lewis (Deputy Director of Programs). Inevitably perhaps, such forceful personalities stand out in one’s reading but also reinforce the recurring sense of eccentric happenstance and improvisation in the BBC’s progress and formulation, if not other aspects of British life. Lewis, for instance, barely eighteen when he fought as a pilot in the Great War, appears to have been little more than a drifter, boasting ‘no profession, no job, no training in anything other than flying’ with ‘a certain unfocused, undirected ability’. Remarkably, he recalled of the BBC’s gestation: ‘We didn’t know what we were doing, we were simply finding something which could be broadcast … it was a sort of free for all in which everybody was free to come up with any idea that seemed likely to be any use.’ Such quotes have the effect of reminding one of the contingencies of both broadcasting as organisation and the nature of its outputs.

As Potter argues, a history of the BBC should not make the mistake of confusing its endurance for continuity, yet both books are imaginative exercises in evoking the entry into British life of broadcasting, its sedimentation and habituation as part of the horizon of everyday life and of the definition of education, information, and entertainment. While this is no longer the preserve of the BBC alone in the United Kingdom, and has not been for a long time, its longevity and mutable character offer a yardstick by which we might measure changing social and cultural relations, and how they have been conceived and mediated. These are most evidently mapped around categories such as class, gender, race, and sexuality, revealing the challenge to the BBC of how it has sought to speak to and for everyone, especially when the conceptual toolkit of those authorised to do so has often proven limited.

Tom Jones visits the BBC Television Centre, 1971 (Keystone Press/Alamy)

Tom Jones visits the BBC Television Centre, 1971 (Keystone Press/Alamy)

One example is Hendy’s chapter on the BBC’s responsiveness to postwar migration. Entitled ‘Strangers’, it echoes Clair Wills’s Lovers and Strangers: An immigrant history of post-war Britain (2017), synthesising a range of sources and his own research to illuminate stories about this moment and its enduring legacy that prove difficult to reconcile to any pat sense of progress. As Hendy comments, much of the immediate coverage of Commonwealth migration was dealt with in journalistic terms, ‘race’ a signifier marking the migrant rather than a term extending to the host communities, portrayed as impacted on by the presence of largely alien and unwelcome newcomers.

Hendy and Potter both report on John Elliot’s 1956 television play A Man From the Sun and its account of West Indian experience in London. Hendy describes how the writer aimed at a ‘new level of realism’ in dealing with his subject, ‘sinking into the background, talking and listening to people, going to parties, to church, to work, and generally being a fly-on-the-wall’. Regardless of the reflexive contributions of progressives like Elliot in the BBC, what is evident overall is a structural failure of imagination across the organisation – to understand, include, represent, and respect a diverse humanity. Certainly, every positive gesture is balanced by an example of an insult proving the rule. Hendy tells of the mistreatment of Jamaican Una Marson and the prejudice she experienced because of her audacity in being creative, expert, and confident. The endurance on television until 1978 of the egregious Black and White Minstrel Show receives particular attention by both books. Analogies abound across the treatment of gender, class, and sexuality, on screen and off, posing questions about the BBC’s role as a leader or follower of social change.

As suggested, while both books touch on similar reference points, they are distinctive and divergent. Hendy seems less interested in the 1970s than does Potter, for whom this is a period of ‘stagnation’ following on the back of the ‘transformation’ of the 1960s. For instance, he covers the establishment of that great educational institution, the Open University, long supported by programming on the BBC2 TV channel. In the days before video recorders, students needed to be up early in the morning or late at night to access subject lectures in broadcast form.

This banal but innovative scheme illustrates the importance of programming as more pronounced in Potter’s history, where prodigious reference to titles is deployed and anchored to institutional and social themes. In one section for instance, we travel through a vista of 1960s radio situation comedy via mentions of The Navy Lark (1959–77) and The Men from the Ministry (1962–77), via popular presenter Kenneth Horne’s Round the Horne (1965–68), to encompass that show’s celebrated ‘Julian and Sandy’ characters. While male homosexuality was illegal until 1967, this duo, realised by Kenneth Williams and Hugh Paddick, used innuendo, double entendre, and camp style in tandem with the subcultural slang polari to reference gay stereo-

types and lifestyles.

Such figures and program titles offer a shorthand for meaning and cultural memory in both books but draw attention also to the degree to which, without extensive elaboration, their specificity will resonate for different readerships. While both authors occasionally include their reader in an address to ‘we’ and ‘us’, the idea that the BBC’s story is solely a British concern is belied by detail of its international role, reach, and impact, making it for Potter ‘the single most important institution generating British soft power and overseas propaganda’. It is curious that in the United Kingdom, while those of the left are critical of it, those that claim to be the voices of conservatism in the country are so unremittingly hostile to the BBC and what it is thought to represent, not simply in its programming but in its very existence. Potter and Hendy are equally invested in an evaluation of the BBC’s value in response to intensified threats and attacks on its remit, its capacity for political ‘balance’, and, through its funding – levied in a licence fee – its sustainability. To be clear, they are both attuned to its contradictions and considerable deficiencies but also to what is at stake should it disappear which is, as they elaborate, an increasingly realistic proposition. Hendy’s closing chapter appraises the BBC as ‘On the Rack’; Potter sees it ‘At Risk’. On one hand, this situation is exacerbated by the BBC’s continued mission: successfully adapting to changing conditions – the coming of digital for instance – but in so doing, expanding and changing to become a creative institution like no other, unrecognisable to its original formulation. For some, the result is that it skews the country’s cultural economy, for others its political economy, the perennial complaint being that the BBC is hopelessly biased and dominated, as in the title of Jean Seaton’s history, by Pinkoes and Traitors (2015). Yet as the former economics editor, Robert Peston, is quoted by Hendy as saying, the idea that the BBC is in any way left-wing is ‘bollocks really’. On the contrary, recent exchanges of personnel between the Conservative Party, its supporters in business, and the BBC’s management and board signal the nature and direction of its politicisation.

What Hendy and Potter both do in different ways is to highlight the problem with making sense of the BBC in a reductive manner that characterises it as having and enforcing on its personnel and audiences a particular social agenda and political outlook. Vitriolic criticism is often focused on a few current affairs programs and the mediation of government policy in particular. Beyond this, the immense variety of operations and output makes it difficult to take seriously accounts of an instrumental political bias or a laying of blame at its door for contemporary ills such as tolerance and inclusivity. Are these objectionable values encoded equally into the children’s television programme Telly Tubbies, into televised church services, radio’s Test Match Special, and the BBC’s website? Of course, the very existence of the BBC’s Asian Network, or the appearance on the latest series of Strictly Come Dancing of Paralympian Ellie Simmonds, are enough to send Daily Mail commentators and some viewers into paroxysms of outrage.

What is equally accessible and effective about the contribution of Hendy’s and Potter’s books is a sense of the complexity of the BBC as a cultural institution. It can be understood in terms of its similarity to other organisations – say in its bureaucracy, hierarchy and specialised roles. But it is also distinctive in nurturing the conditions necessary to produce innovation, authenticity, and commitment in its workforce, whether in reporting the world or in its creative imagination. To understand this complexity is a useful corrective to aspects of everyday media studies and ‘common-sense’ theories which generalise about the apparent power and manipulation exerted by the BBC.

The BBC may not survive in its current form, if at all – not because it lacks an abiding purpose but because the breadth of the values it has represented are possibly inimical to contemporary Britain, which would be as unrecognisable to its founders as would the broadcaster they invented. The centenary of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation in 2032 will no doubt generate similar attention from historians. As with Hendy’s and Potter’s work, the question is what to do with accounts of institutions which have played a part in defining, embodying, and underwriting nation, community, and culture. Whether it operates satisfactorily or not, a public broadcasting institution is at the heart of a national conversation and can be held accountable in a manner unlike commercial television, radio, or the press. As is apparent in these books, a history of such institutions is also a means of assessing the future. As Potter cautions, ‘Anyone who cares about what we read, watch, and listen to, on television, radio, or online, should think about what life would be like without the BBC, and about how the Corporation might, in the future, find new and better ways to serve all our needs.’

Comments powered by CComment