- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The real Edith Berrys

- Article Subtitle: Why Australians turned to Geneva

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In October 2022, the United Nations announced that its Total Digital Access to the League of Nations Archives Project (LONTAD) was complete. For the past five years, archivists in Geneva have been preserving, scanning, and cataloguing more than fourteen million pages of historical documents, making them accessible to researchers around the world. Harnessing a technology that people a century ago could hardly imagine, this project has extended the League of Nations’ foundational values of sharing knowledge and cooperating across borders into the twenty-first century.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: League of Nations Council Chamber in the Palace of Nations, Geneva, c.1922 (Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Michelle Staff reviews 'The Australians at Geneva: Internationalist diplomacy in the interwar years' by James Cotton

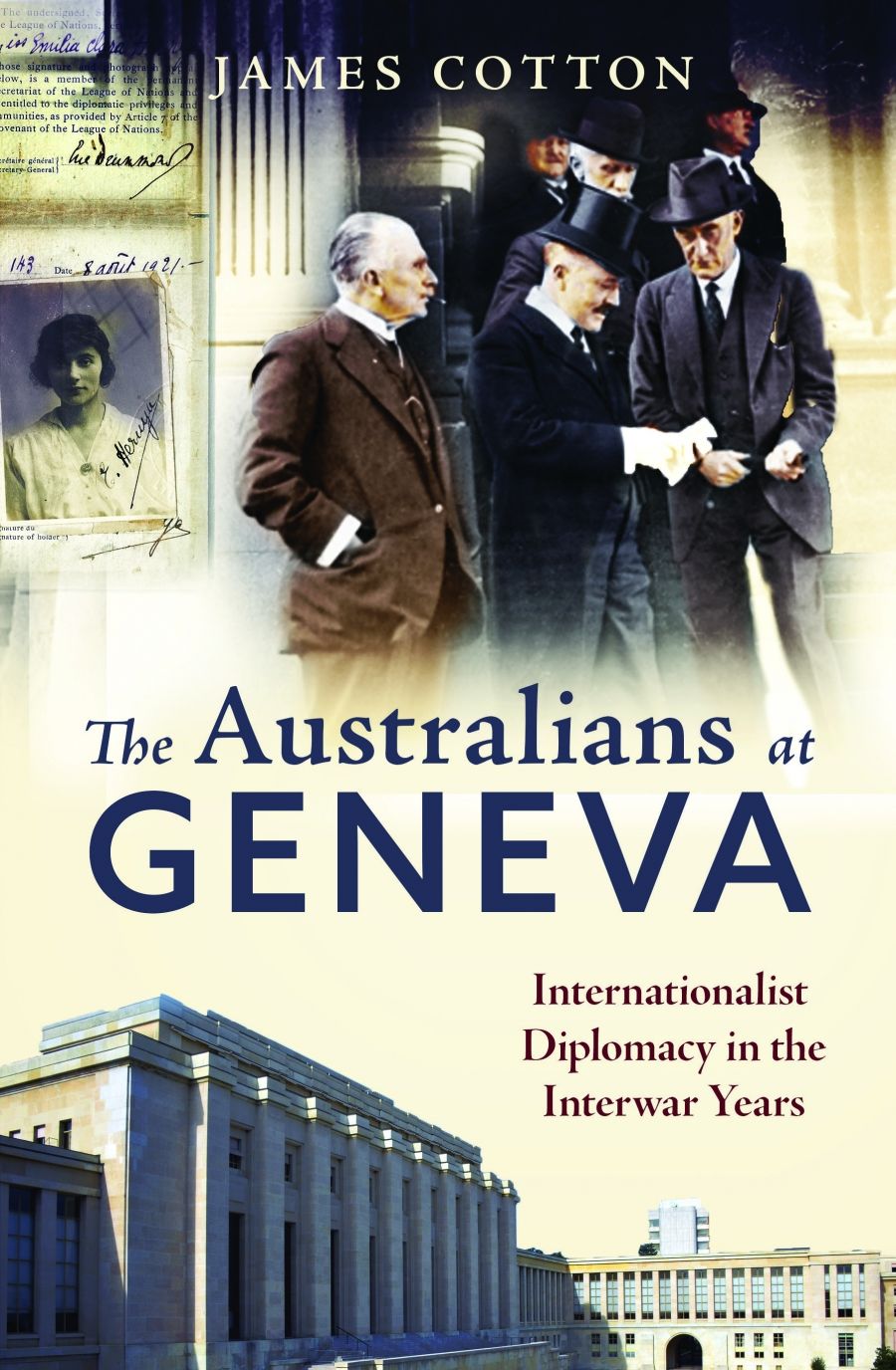

- Book 1 Title: The Australians at Geneva

- Book 1 Subtitle: Internationalist diplomacy in the interwar years

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $39.99 pb, 255 pp

In setting up this story, Cotton offers a useful overview of Australia’s relationship with the League during what was a ‘formative phase’ of the country’s diplomatic activities. While Gallipoli is often flagged as the ‘birth of the nation’, Australia’s independent membership of the League was central to its emerging sense of nationhood. At the same time, imperial dynamics continued to be influential; many contemporaries promoted the similarities between this internationalist experiment and the Empire–Commonwealth ideal. Cotton appropriately emphasises the reservations of authorities who were desperate to safeguard the White Australia policy from international scrutiny, evoking the limits of the interwar spirit of internationalism. Alongside this exploration of the League’s diplomacy, he also shows how ‘technical work’ – across areas as diverse as the plight of refugees and global health – formed a growing part of Geneva’s activities.

The bulk of The Australians at Geneva is devoted to the diverse array of individuals who engaged with the League. It concentrates on those who were not government representatives but instead League and ILO employees, unofficial delegates, visitors, and lobbyists. As Cotton rightly points out, readers would be more likely to know of novelist Frank Moorhouse’s fictional character Edith Campbell Berry than of any of the real Australians who spent time in Geneva.

The book’s three central chapters each focus on an under-recognised Australian who worked in Geneva: William Caldwell (an ILO employee), Raymond Kershaw (the first Australian administrator in the League’s Secretariat), and Hessel Duncan Hall (who worked in the Secretariat’s Opium and Information Sections). Their stories show Australians making major contributions to the work of these organisations while also seeking to raise support among wider audiences at home. Although they were not of especially privileged backgrounds, all three were white, Oxford-educated men who spent much of their lives in the Northern Hemisphere – common characteristics worthy of further interrogation.

Following these in-depth portraits, Cotton draws attention to the many other people who engaged with the League and the ILO. He highlights the experiences of Australian employer and worker representatives, ‘temporary collaborators’, other ancillary staff, and even an MI6 spy, albeit in less detail. These short biographical sketches showcase the varied activities Australians undertook at Geneva as ‘active if unobtrusive agents of a major turn to internationalism’. This work is underpinned by thorough research that pieces together archival fragments from across Australia, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Here Cotton also explores the contributions of Australian women such as the Perth-based feminist, Bessie Rischbieth, who successfully argued for a woman to be included in the Australian delegation to the League’s yearly Assembly (and who fulfilled this role in 1935). Although no single woman is given a whole chapter, the discussion evokes the broader context of feminist activism that intersected with internationalist currents at this time, showing how women were active, passionate, and independent contributors to conversations about the League.

These subjects constituted, in Cotton’s words, an ‘untypical group’. Only a limited number of people worked for the League and the ILO, and it was certainly not the norm for Australians to be so actively involved with far-away Geneva. So what should we make of such unrepresentative lives? They may not reflect the experiences of most Australians, but they are important for understanding what was possible at this moment when the country was finding its feet and people around the world were rethinking the norms of global politics. Such life stories provide opportunities for understanding the diverse experiences and ideas people had during the interwar years, as well as the ways in which individual outlooks met broader structural factors such as settler colonialism to produce political and intellectual thought.

While this book’s scope and purpose do not always allow the author to explain what each of these lives reveals about how and why Australians turned to Geneva, by shedding light on them it will surely stimulate interest in this topic and provide a strong basis for future analysis. The gender dynamics shaping Australians’ relationships with the League, for example, are ripe for further exploration. So are questions about how Australians who were less globally mobile engaged with Geneva from afar. These, among others, are important tasks for historians to tackle next.

This book was created through in-person visits to Geneva before the League’s vast quantities of archival material were made available to researchers from the comfort of their own desks. The Australian historiography it will help to spur on will benefit from the greatly increased access made possible by the LONTAD project. The Australians at Geneva is a timely addition to ongoing efforts to reconsider this early experiment in global governance. In a world that is at once even more connected than the League’s founders could have imagined and persistently fractured, understanding internationalism is just as pressing as ever.

Comments powered by CComment