- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Seizing an opportunity

- Article Subtitle: A diaristic memoir from John Clark

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

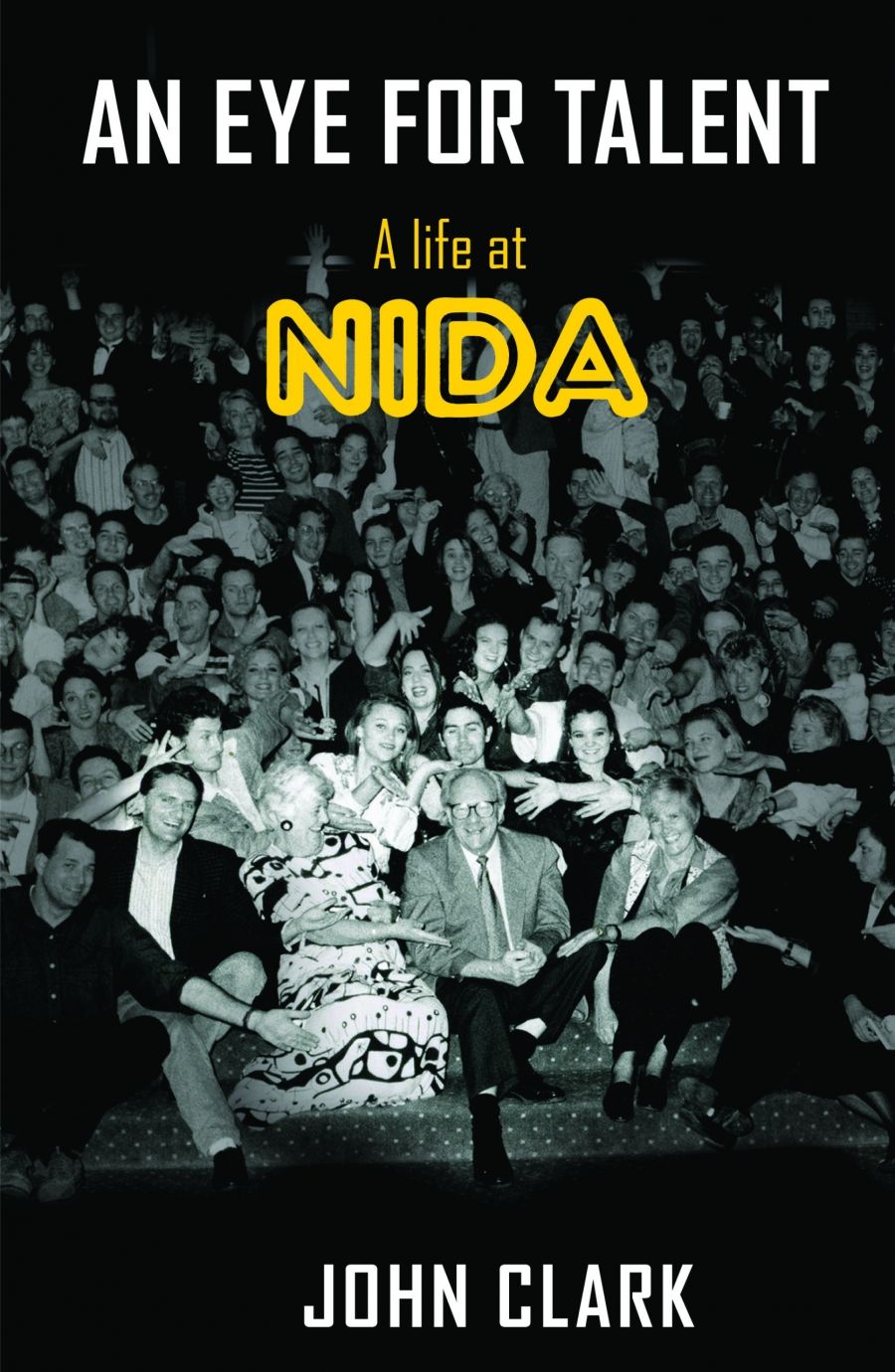

Clark (no ‘e’) may not feel misunderstood exactly, but his memoir, An Eye for Talent – a diaristic account of his remarkably enduring directorship of the National Institute of Dramatic Art (NIDA) from 1969 to 2004 – certainly reads like the seizing of an opportunity to burnish the author’s legacy.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Ben Brooker reviews 'An Eye for Talent: A life at NIDA' by John Clark

- Book 1 Title: An Eye for Talent

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life at NIDA

- Book 1 Biblio: Coach House Books, $39.99 pb, 368 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/an-eye-for-talent-john-clark/book/9781760627508.html

Where Clark’s pragmatic account differs from its aforementioned predecessors – besides being far drier and less personally revealing – is in placing the creation of NIDA in 1958 as an equally important milestone in the development of Australian theatre as, in Julian Meyrick’s words, ‘a project, a set of meaningful relationships rather than a heap of contingent outcomes’.

From the start, NIDA was intended to be, as Clark writes, ‘not an academic drama school but an artistic organisation with an appetite for risk and invention’. By the mid-1950s there was wide agreement within the fledgling industry that ‘a vocational theatre school would have a profound effect on the development of a genuine Australian theatre’. That would entail, in the eyes of inaugural NIDA Director Robert Quentin, a style of acting that was ‘simple, direct and vigorous’, neither as ‘correct’ as English acting nor as

‘introverted and emotionally self-indulgent’ as the then new American Method school.

In 1963, following ‘three years in a university no-man’s land’, NIDA was given a permanent home in Sydney: an obscure collection of Kensington Racecourse buildings owned by the University of New South Wales which, though virtually derelict, would house the institution for the next twenty-four years, a period Clark notes is still referred to as ‘a golden age’ by senior graduates.

What follows, at least in this telling, are decades of rags-to-riches ascendency, much of which Clark indexes to the long list of ‘old boys’ – actors like Mel Gibson, Cate Blanchett, Hugo Weaving, and Sam Worthington, as well as numerous designers and technicians – who went on to achieve fame and success in Hollywood. Perhaps there is no other way to boil down the profound cultural impact of an institution like NIDA than to endlessly name-drop like this, but the result begins to resemble one of those useful but colourless official histories that line the shelves of theatre foyer book stands.

There are, disappointingly, few admissions of failure here, only approving critiques of NIDA productions, as from the seemingly ever-supportive H.G Kippax of The Sydney Morning Herald, are quoted – and Clark gives little insight into his evolution as either director or administrator. The reader is left to speculate on Clark’s directorial craft and educational ethos, which are only ever discussed in the most general terms: ‘teach the person not the subject’, ‘training is cumulative not sequential’, and so on.

Readers of Clark’s generation may be unbothered by his relative social conservatism – perhaps to be expected of someone who grew up in 1950s Tasmania – but for millennials like me the book makes for uncomfortable reading at times. Women are frequently referred to as ‘girls’. Early NIDA productions involving actors in yellowface and blackface are described with little critical reflection. In the book’s final pages, Clark bewails theatre companies that are more ‘concern[ed] for diversity and gender … than talent and skill’ without, curiously, acknowledging NIDA’s history of systemic and institutionalised racism, brought to light in 2020 by a group of alumni, students, and former staff. Significant cultural change followed, but Clark has little good to say about NIDA’s governance on either side of his resignation in 2004.

The neo-liberalisation of the higher education sector, as well as NIDA’s increasingly academic turn under a succession of chairs from the 1980s onwards, clearly still rankles with the author. Clark was tempted to resign years before he did, but writes that that would have ‘handed victory to the vipers. Better to take arms against a sea of academics and lawyers – and by opposing, end them.’

Between these pages, it is hard to get the measure of Clark’s success in this. By his own admission, when he left the board (remaining a member of the NIDA Company), his knowledge of the institution was limited to ‘annual general meetings, play productions and to publications’. In his newfound capacity as an observer, he bristles at ‘the semi-commercial Open Program begin[ning] to overshadow the core business of the school’.

That’s as may be, but another kind of shadow – that of Clark’s nostalgia for ‘the glory days’ – is being cast here too. In a recent Hollywood Reporter article on the top twenty-five drama schools in the world, NIDA – currently led by graduate John Bashford – placed a more than respectable fourteenth. The show, in other words, goes on, something for which Clark might have justifiably claimed some credit had he chosen to end this book on a less prematurely eulogistic note.

Comments powered by CComment