- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Pacific imaginary

- Article Subtitle: Rethinking a monumental work

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the 1990s, I was a doctoral student at the University of Melbourne writing on the representations of race in the School of Historical Studies. Geoffrey Dutton’s White on Black: The Australian Aborigine portrayed in art (1974) and Bernard Smith’s European Vision and the South Pacific were essential reading. Over the subsequent three decades, interest in Dutton’s White on Black seems to have languished, but Smith’s magnum opus remains an indispensable text. Writing in Meanjin in 1960, Robert Brissenden noted that European Vision was ‘an extremely valuable and distinguished piece of work, one to which historians and scholars in many fields will be gratefully indebted for a long time’. I doubt he could have possibly imagined that sixty-two years later we would be reading the third edition of this monumental work, now edited by Smith’s biographer, art historian Sheridan Palmer, with an excellent introduction and contextual essay by Palmer and Greg Lehman.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

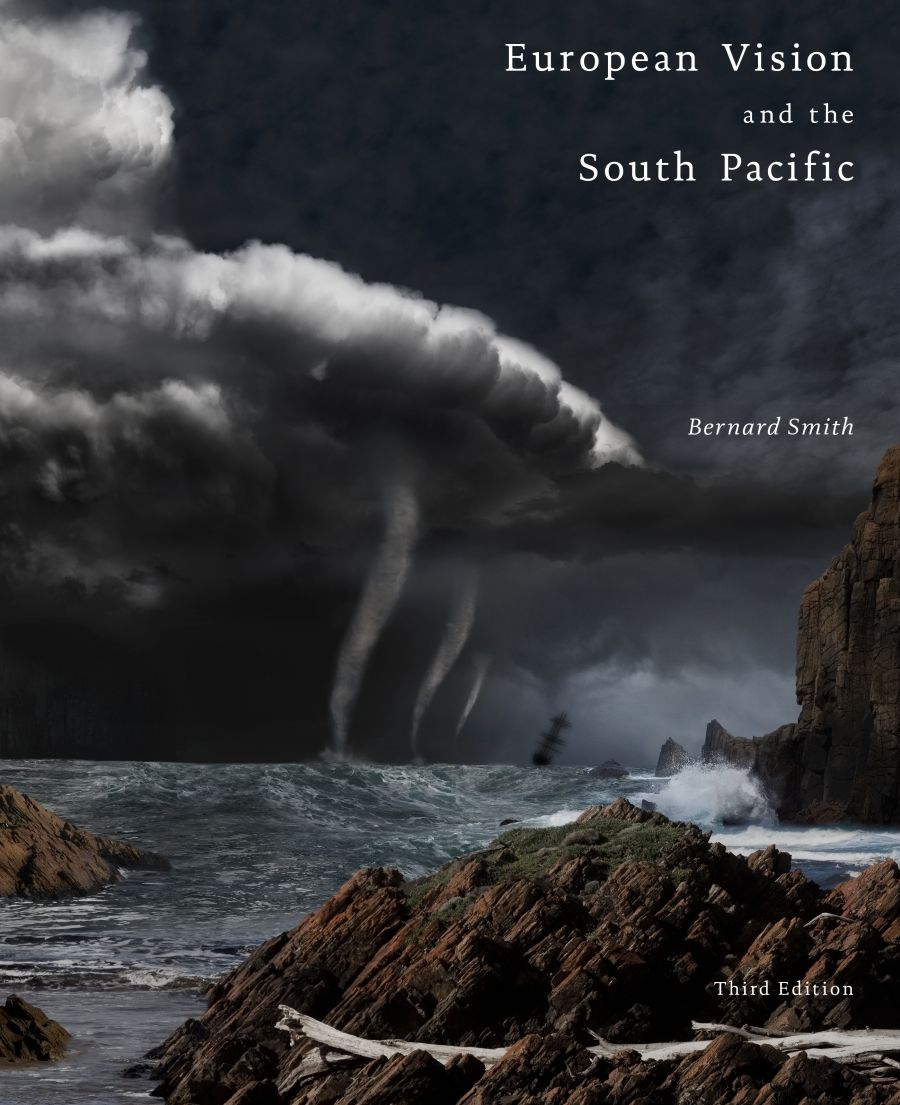

- Article Hero Image Caption: Hessel Gerritsz, Mar del Sur, Mar Pacifico, Map of the Pacific, 1622 (Kattigara/Wikimedia Commons)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Lynette Russell reviews 'European Vision and the South Pacific,Third Edition' by Bernard Smith

- Book 1 Title: European Vision and the South Pacific, Third Edition

- Book 1 Biblio: The Miegunyah Press, $49.99 pb, 370 pp

The South Pacific is the stuff of legends, a beacon for tourists, renowned for ‘off the beaten track’ beach holidays. More often these days, we think of parts of the Pacific as endangered due to sea level rises, climate change, and environmental catastrophe. The Pacific is the largest and deepest of our planet’s oceans, known for millennia to countless generations of islanders. Yet it was unknown to Europeans until the sixteenth century. Although many historians and Pacific scholars have carefully documented the tumultuous impact of European exploration and subsequent colonisation, Smith, sixty years ago, demonstrated that the Pacific region also affected scientists, scholars, and even the general public in Europe. The Pacific, its cultures, and people played a key role in the European imaginary. This impact included the crumbling of creationism, a rethinking of Linnaean categorisations, and the rise of science in the understanding of the larger world.

However, exploration was not only a British affair. Over hundreds of years, the French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch mapped and encountered the Pacific islands and their peoples and cultures. Much less emphasis has been placed on the non-English speaking explorers, scientists, and artists. This year marks the four hundredth anniversary of the publication of what is widely regarded as the first map of the Pacific Ocean, in a significant atlas by Dutch cartographer Hessel Gerritsz (1581–1632). In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Gerritsz’s map, along with publications by the Portuguese navigator Pedro Fernandes de Queirós (1563–1614), had a significant impact on Dutch and French depictions of the South Pacific and helped popularise the name ‘Australia’. Such is the Australian obsession with the British that these earlier voyages and their depictions of peoples and cultures are a mere footnote in most history books. The pandemic interfered with the fanfare commemorating the two hundred and fiftieth anniversary of Captain Cook’s mapping of the Australian east coast, a milestone that illustrates how Anglocentric our histories tend to be. Compare this with the commemoration of the Dutch charting of the Western Australian coast, which was virtually confined to Perth. The Cook celebrations were meant to be Australia-wide, with a circumnavigation à la Matthew Flinders touted as a possibility. Smith, by focusing on the late eighteenth century onwards, manages to reinscribe the centrality of British exploration.

Since the first edition of European Vision and the South Pacific, Sheridan and Lehman note, there has been enormous growth in interest both in Indigenous cultures, and in the dispossession, resistance, and resurgence of Indigenous people. In each edition of Smith’s book, the text is largely the same. The second edition was moderately expanded and more fully illustrated. In the third edition, only typographical errors are corrected, and there are fewer images. In their own way, both editions’ introductions and framing essays offer an excellent overview of the ways in which the field has developed. The reissuing of Smith’s two previous introductions is useful and can be read as an iterative discourse across six decades. As Sheridan and Lehman note: ‘Not only is this work a significant text for understanding the world in which we live, it critically engages with the humanities, colonial histories and cultural relativism that reverberate within the contemporary phenomena of globalisation.’ Thus, European Vision continues to shape the ways that we see and apprehend the past. Appropriately framed, it is almost timeless.

Melbourne University Press, under the Miegunyah imprint, has produced a handsome volume and a fitting successor to the previous editions. I do, however, lament the reduction in the number of illustrations, and I will probably refer to the second edition when I need to consider images. All three volumes will sit on my bookshelf, perhaps not dipped into as often as in the past, but standing as a fine achievement that was sixty years in the making. Kate Challis – art historian, designer, granddaughter, and literary executor – is clearly passionate about Bernard Smith’s legacy. I am in complete agreement with her assessment in the preface that European Vision and the South Pacific ‘pioneer[ed] global cross-cultural and interdisciplinary studies’ and ‘its ongoing importance has never diminished’.

Comments powered by CComment