- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

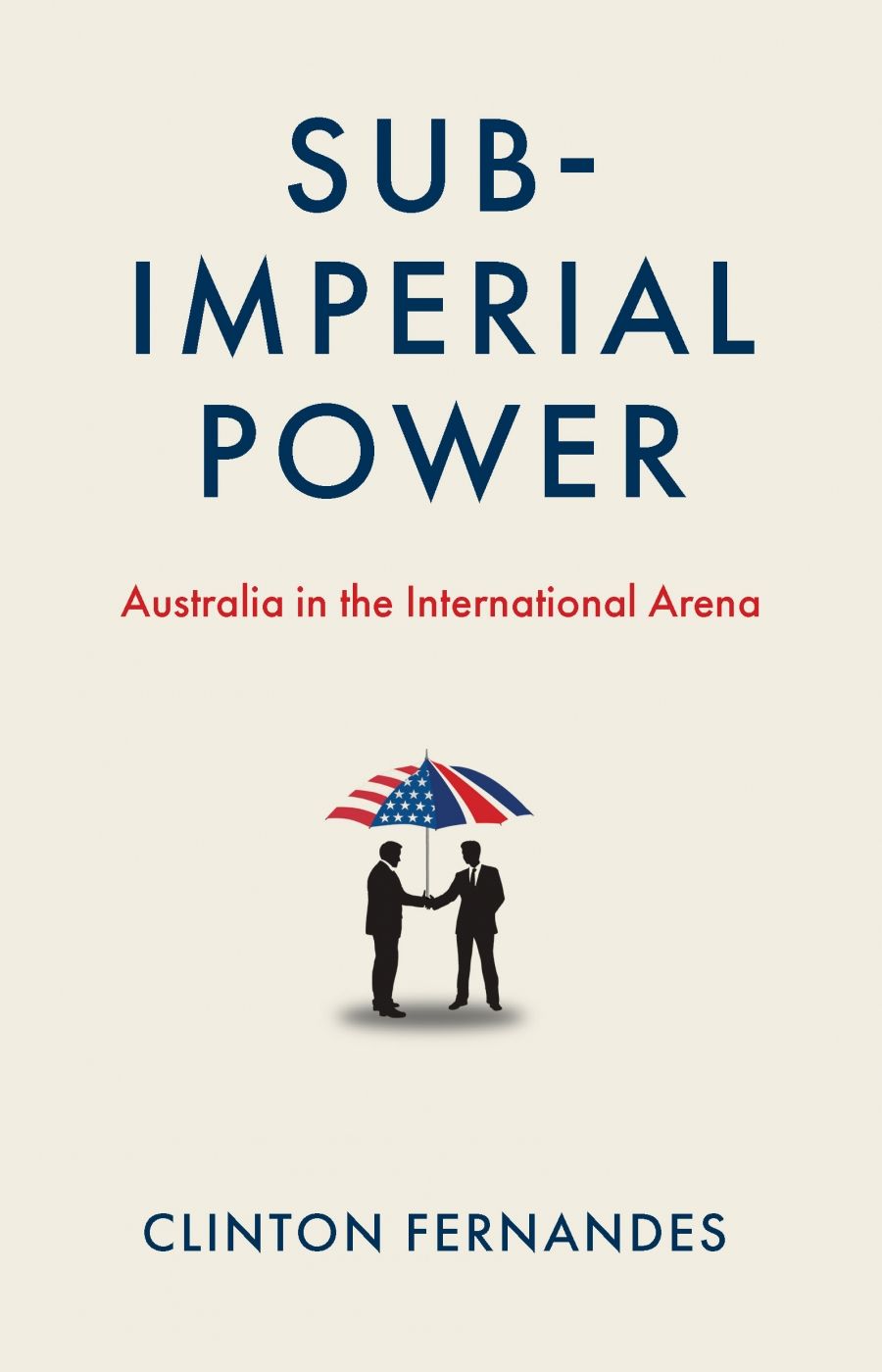

- Article Title: Playing deputy sheriff

- Article Subtitle: Clinton Fernandes’s compelling new book

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When the Howard government committed Australian troops to fight in Afghanistan in 2001, and later in Iraq, it did so without recourse to parliament or the courts. Not only can the prime minister sanction the despatch of the nation’s forces to fight overseas, he or she has no need of parliamentary approval. Indeed, there is no requirement to debate such a proposal before a decision is made. Australia has no equivalent of the US War Powers Resolution of 1973, which limits the president’s freedom to make war.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Kevin Foster reviews 'Subimperial Power: Australia in the international arena' by Clinton Fernandes

- Book 1 Title: Subimperial Power

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australia in the international arena

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $24.99 pb, 175 pp

If Australia’s wars have been Australia’s choice, there has been a remarkable consistency about the conflicts that it has elected to join and the role in world affairs that this has afforded it. As Clinton Fernandes points out, the much-trumpeted ‘rules-based international order’ that Australians have fought and died to uphold is nothing more than a euphemism for an imperial order in which the United States sets the rules, its allies assume their allotted supporting roles, and the rest of the world does as it is told. Demonstrating support for the United States ranks ahead of all other priorities in Australian foreign policy, and every opportunity to reinforce this fidelity is taken up, regardless of risk or costs. When the Howard government committed the nation’s forces to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, over the protestations of the Labor opposition, its principal strategic considerations were political, not military. Its modest contingent of ground forces largely stayed out of trouble in the far west of the country. This was such a quiet area that Special Forces personnel who were deployed there were subject to regular ribbing from their coalition colleagues about the pristine condition of their assault vehicles. It is little wonder

that their equipment scarcely lost its showroom sheen as the Australians were not in Iraq to provide muscle – their mere presence fulfilled the nation’s principal political goals. A confidential Australian Army study of the Iraq War revealed that the true strategic intent of Australia’s military commitment was to safeguard and improve the nation’s relations with the United States. Of course, this was not what the Howard government told the public. Its repeated assertions that the invasion of Iraq was a defensive measure – to discover and destroy Saddam Hussein’s Weapons of Mass Destruction and ensure that the threat of Islamic terrorism was confronted in the Middle East rather than the suburbs of Melbourne or Sydney – were just ‘mandatory rhetoric’ calculated to keep the public onside. ‘The true centre of gravity, from Canberra’s perspective,’ the secret Army study revealed, ‘was to not jeopardise the Washington alliance.’

If this wasn’t bad enough, Fernandes reveals that far from protecting the Australian public from the threat of Islamist terrorism, Australian intelligence, like its British and US counterparts, knew that the invasion of Iraq, along with other acts of Western adventurism in the Middle East and North Africa, would directly increase that threat and produce a significant expansion of terrorist activity. That is to say, the Australian government knowingly made foreign policy decisions that exposed the Australian public to greater risk. Australian foreign policy is a matter of priorities and demonstrating the nation’s relevance to the United States clearly occupies a higher priority than safeguarding the security of the Australian people.

If you think that the Australian government is above such cold calculation, consider the case of the Poate family. Private Robert Poate was one of three Australian soldiers murdered by a rogue Afghan Army sergeant, Hekmatullah, in a green-on-blue attack at an Australian Forward Operating Base in August 2012. Instead of facing the death penalty, after seven years in an Afghan jail Hekmatullah was moved to Qatar, where the United States and the Taliban were hammering out a peace agreement – without the involvement of the Afghan government. At the conclusion of these talks, despite the protestations of Poate’s father, Hugh, and the evident discomfort of some Australian politicians, the United States approved Hekmatullah’s release from custody. He walked free when Kabul fell to the Taliban.

The hard truth for the Poate family and all those who have lost loved ones to terrorist attacks or suffered their effects, the government would argue, is that the prioritisation of our relations with the United States has been in the country’s interest. It has ensured that, for more than eighty years, ever since the British surrendered Singapore and Australia turned to the United States to underwrite its security, the country has finished on the winning side in the fights that mattered and has reaped the political and economic benefits of sub-imperial service. In return for its faithful projection of US power in the region, its demonisation of Washington’s enemies and its embrace of their friends, even when this has jeopardised the country’s relationship with its principal trading partner, Australia has benefited from the rules-based international order. That this order has preserved the interests of a small coterie of developed nations at the expense of a host of developing countries and their people, locking them into a subordinate role in the supply chain providing raw materials, cheap labour, and cut-price manufactures, makes clear that the order Australia defends looks manifestly unfair to those disadvantaged by it, while the rules it is founded on are ultimately underpinned by the threat of brute power.

Yet Australia is both the agent and the object of this rules-based order, both a beneficiary and a hostage. Foreign investors own up to seventy-five per cent of shares in the nation’s top twenty companies that comprise around half of the market capitalisation of the Australian Stock Exchange. US-based investors are the largest shareholders in sixteen of these top twenty companies. As owners of the equity, it is these shareholders that determine the corporations’ priorities. A dependent economy is no basis for an independent foreign policy. Hence, Australia pursues its strategic interests by working, under the auspices of the United States, to sustain an integrated economic system that supports the interests of global investors. The prosperity of élite Australian investors, and with it the Australian economy, is underwritten by the same conditions that ensure the prosperity of élite US investors.

As US alarm at China’s assertiveness has grown, so Australia’s political position has become increasingly uncomfortable. As the recent deterioration in its relations with China demonstrates, Australia’s sub-imperial lieutenancy is in open warfare with its economic imperatives. The lessons of history show that Australia’s room for manoeuvre is circumscribed and suggest that the most consequential decisions about the nation’s future for almost a century will either be taken out of its hands or be determined by the interests of others.

Sixty thousand years of unbroken Indigenous occupation make a mockery of the national anthem’s former boast that we are ‘young’. Clinton Fernandes’s remarkable book makes a compelling case that our freedom is hardly less illusory.

Comments powered by CComment