- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Reimagining Iris

- Article Subtitle: An exhilarating squeezebox of a novel

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The accordion, or squeezebox, takes its name from the German Akkordeon, meaning a ‘musical chorus’ or ‘chorus of sounds’. This box-shaped aerophonic instrument makes music when keys on its sides are pressed, one side mostly melody, the other chords. Squeezing the instrument and playing with both hands, the musician dexterously produces polyphonous music.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Felicity Plunkett reviews 'Iris' by Fiona Kelly McGregor

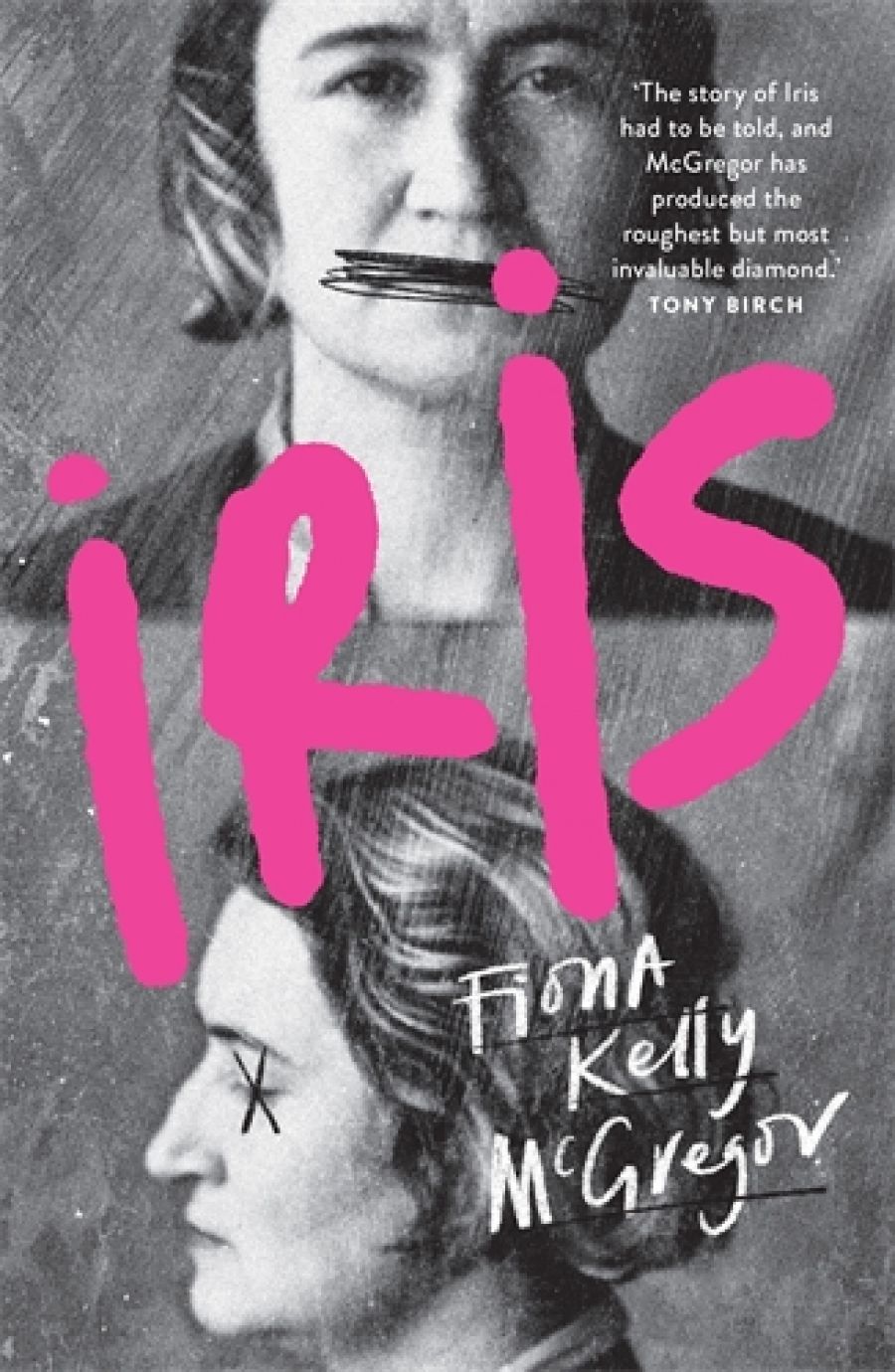

- Book 1 Title: Iris

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $34.99 pb, 464 pp

McGregor’s Iris is a fictional version of Iris Eileen Mary Webber, née Shingles. More is known about Tilly Devine (‘Queen of Woolloomooloo’) and Kate Leigh, women who battled for control of inner Sydney, running razor gangs, brothels, and ‘sly grog’ shops, and circulating stolen goods and drugs. While it was illegal in New South Wales for men to run brothels or to profit from sex work, these laws did not extend to women, creating the opportunity that Devine and Leigh seized. Both were formidable, but also ruthless, attacking women and men, something their legacy blurs. There is now a wine bar in Darlinghurst called Love, Tilly Devine; it proffers fine wine (legally) and ‘Italian nibbles’, and snaffles its distractingly twee name from someone who was probably a criminal sociopath. Iris, poor, savagely assaulted from a young age, with no one to protect her but herself and a shiv or knuckleduster, tends to be remembered less affectionately.

Fact and fiction work together in this two-handed artistic project, with meticulous research into Iris’s life and milieu given breath through fiction’s imagining. The nature of evidence and testimony – and the way the law can crimp and thwart the lives of those with little choice but to work outside it – are related strands. Literate, canny Iris spends a lot of time in court, and is aware of the law’s performativity and tripwires. ‘Every time you think you’ve won,’ she observes, ‘you need to take a step back and look again. Usually up. That’s where the real winners are. Looking up you see the Law. And the rich people it protects.’

McGregor delivers slivers of Iris’s life, unchronologically; she works deeply in the grain of each moment. This includes slang of the era: ‘lamping’, ‘yiking’, and ‘jobbing’, ‘tootsies’ and ‘angie’. Narrative momentum builds around questions of what Iris has (or hasn’t) done. This draws readers close to Iris before there is any opportunity to assess her guilt, forestalling easy judgement. Slashes of narrative depict a culture of risk and betrayal, violent reprisal, subterfuge, and raids. Lives split by incarceration, flight, and life-saving self-invention are portrayed in jagged chapters, as they are lived.

For Iris, this begins with an early marriage to an older man, the trauma of solitary miscarriage, and incarceration for shooting her husband in the buttock. She moves to Sydney and is swept into sex work. Her story is surrounded by other people’s, especially those of women in similar circumstances. This produces a choral or chord-like effect against the melody of Iris’s narrative. There is a plethora of characters to keep track of, just as Iris needs to stay alert to a host of potential enemies.

Braiding chapters in the first person with others in the third, McGregor explores how the life of a woman like Iris can be seen, and how she evades this. This includes heteronormative and sexist lenses through which women’s lives are judged, as well as caricatures of women who don’t conform. In On Lies, Secrets and Silence (1979), American poet Adrienne Rich describes the unspoken that becomes unspeakable, including

[w]hatever is unnamed, undepicted in images, whatever is omitted from biography, censored in collections of letters, whatever is misnamed as something else, made difficult-to-come-by, whatever is buried in memory by the collapse of meaning under an inadequate or lying language …

McGregor’s work across forms has always boldly spoken the unspeakable. Through the depiction of Lillian Armfield, a police officer keenly interested in Iris, lesbophobia comes into focus. And as Iris salvages sexual agency from objectification, she weighs the bliss of erotic discovery with her beloved Maisie against internalised homophobia, kissing ‘the smell of myself all over her face, rank and fascinating’. This gathering of narrative slivers embodies a refusal of the linear narrative so often a vehicle for stories shaped with moral conclusions, especially the ‘Reader, I married him’ or ‘shedunnit’ of conventional closure. Narrative porousness – McGregor keeps the weave of the novel open – formally enacts imaginative and political resistance, witnessing what is unknowable through even the most careful research.

A love story and criminal proceedings jostle alongside other parts of a life, including Iris’s cleverness (even Armfield wrote that Iris had a ‘brilliant brain’) and passions. Iris’s life is grim, yet there is quiet satisfaction in moments sharing a meal with women friends, celebrating a win by buying a tin bath-tub, or consoling herself by playing the accordion for her own pleasure. Though the novel is partly about restoring to Iris a sense of a life and depicting her agency, McGregor is both too smart and too ethical to pretend to know her fully – though she’s a vivid character. In an afterword, McGregor describes offering a story ‘suspended between the possible and the probable’.

This is an exhilarating squeezebox of a novel, fine-grained in its historical detail and its reimagining of a time- and stereotype-flattened woman. The instrument of the novel, in McGregor’s hands and with her ferocious intelligence, makes rich, insubordinate music.

Comments powered by CComment