- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Creative conundrums

- Article Subtitle: Australia’s ‘foundational thinker’

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the centenary of Jeremy Bentham’s death in 1932, there was widespread and somewhat macabre interest in the Australian press in the commemorative dinner at University College London, at which Bentham’s famous auto-icon made an appearance as the guest of honour. Some of the more serious commentary sought to educate readers about this ‘human bridge between the thought of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries’ and more especially about his relationship to Australia. New South Wales was established as an experimental penal colony just as Bentham (1748–1832) was reaching the height of his powers, and could hardly fail to play a dynamic and critical role within his thinking on crime and punishment. Given the origins and nature of the colonies that became Australia’s states, they could not but bear some imprint from the house-philosopher of the Victorian British state, making Bentham, in Judith Brett’s assessment, Australia’s ‘foundational thinker’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Gordon Pentland reviews 'Jeremy Bentham and Australia' and 'Panopticon versus New South Wales and Other Writings on Australia', edited by Tim Causer, Margot Finn and Philip Schofield

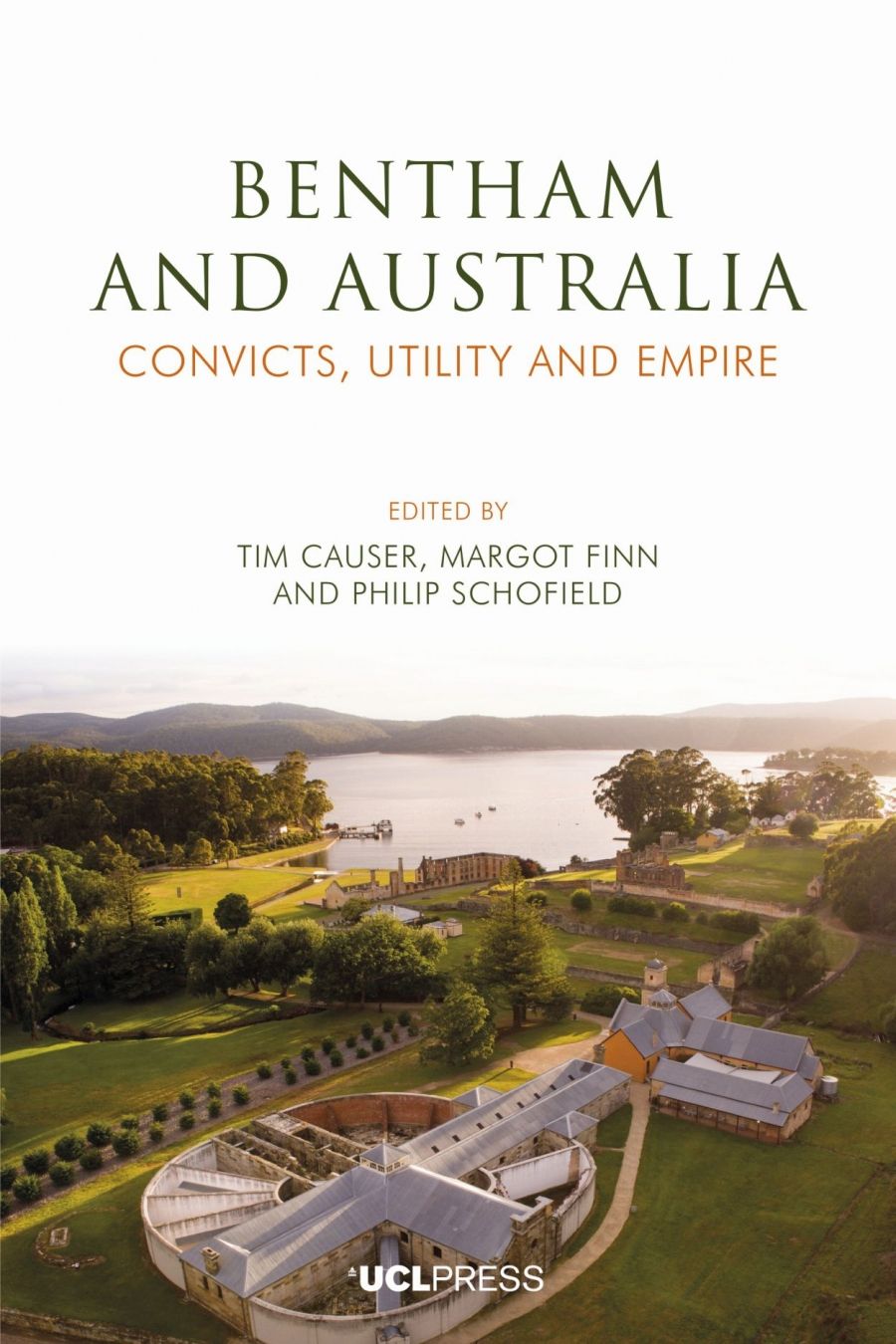

- Book 1 Title: Jeremy Bentham and Australia

- Book 1 Subtitle: Convicts, utility and empire

- Book 1 Biblio: UCL Press, £30 pb, 422 pp

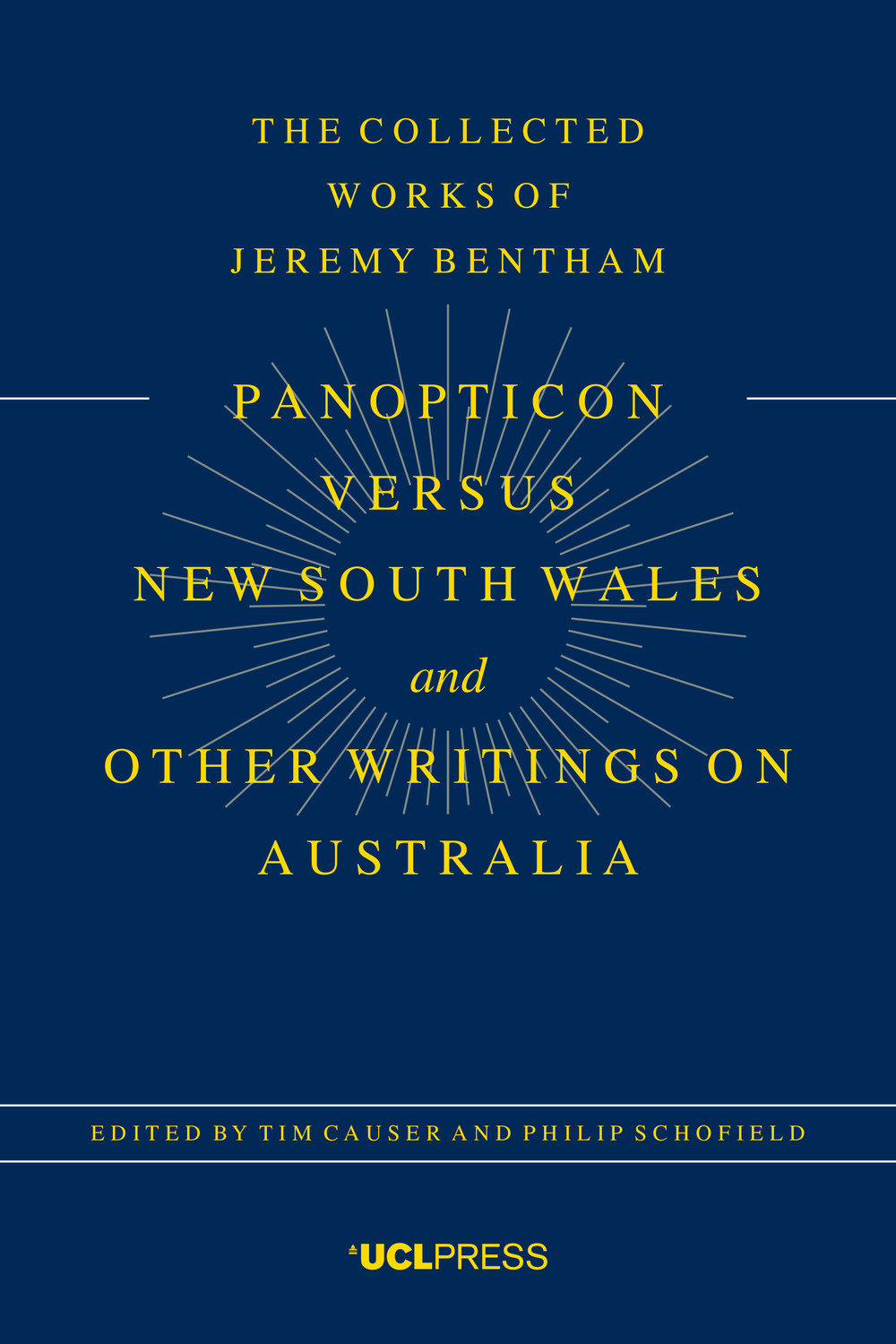

- Book 2 Title: Panopticon versus New South Wales and Other Writings on Australia

- Book 2 Biblio: UCL Press, £25 pb, 616 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

The texts that comprise the critical edition are clustered around the 1790s and the early 1800s when Bentham was restlessly (and ultimately fruitlessly) puffing and pressing on British ministers his panopticon scheme, a proposal for a penal institution with an emphasis on surveillance, discipline, and the reform of offenders. The last text – the unpublished 1831 ‘Colonization Company Proposal’ – provides a substantial sketch for a colony in southern Australia and raises the tantalising puzzle of Bentham’s more general views on colonies and colonialism, something taken up gamely by a number of contributors to the companion volume.

There was an inevitably symbiotic relationship between Bentham the penal entrepreneur and Bentham the commentator on Australia. As Deborah Oxley highlights in her opening essay to the collection, Bentham was operating at a moment pregnant with opportunity. The burgeoning ‘criminal fiscal state’ was slowly drifting away from criminal justice experimentation and exemplary capital punishment towards more comprehensive and expensive schemes. Bentham’s panopticon was a move within that marketplace; transportation was the great rival product. For the most part, Bentham treated Australia as a foil, a monitory failure to meet the five ‘ends of penal justice’ – example, reformation, incapacitation, compensation, and economy. Needless to say, the panopticon met those ends impeccably.

Ironies and the unintended consequences of Bentham’s writings run through many of the essays. As Hamish Maxwell-Stewart makes clear, Bentham and his subsequent interpreters derided transportation and penal colonies as not only ineffectual, expensive, and unconstitutional, but also as regressive. Transportation and the convict colony reeked of the lash and direct judicial violence on bodies. Such methods came to be seen, especially through a crude reading of Foucault, as relics or accidental ‘survivals’, out of time in a nineteenth century filled with scientific prisons, workhouses, and schools. Following Maxwell-Stewart’s lead, a range of contributions flesh out his ‘colonial panopticon’ – interlocking systems of surveillance and discipline – through detailed examples. The ‘colonial reinterpretation’ of the panopticon in the shape of Fremantle Gaol on the Swan River Colony, and the incarceration of Indigenous people on Rottnest Island, almost out-Benthamed Bentham.

There was clearly an opportunistic dimension to Bentham’s engagement with the Great Southern Land. As soon as it became clear that his panopticon project was a lame duck, he dropped any sustained interest in the continent until the end of his life. But in his commentary he also ranged beyond his penal checklist in ways that had unforeseen consequences. This was perhaps clearest in two works in the critical edition, the published Plea for the Constitution (1803) and the unpublished ‘Colonization Company Proposal’.

The first text’s unwieldy full title reveals the breadth of its challenge to the constitutionality and legality of the New South Wales colony: A Plea for the Constitution: shewing the enormities committed to the oppression of British Subjects, innocent as well as Guilty, in breach of Magna Carta, the Habeas Corpus Act, the Petition of Rights; as Likewise of the several Transportation Acts; in and by the design, foundation, and government of the penal colony of New South Wales: including an inquiry into the right of the Crown to legislate without Parliament in Trinidad, and other British colonies. Here again, translation, adaptation, and reinterpretation are key themes. Edward Cavanagh shows the submerged continuing power of imperial thinking within Bentham’s apparently more ‘domestic’ focus after 1803 and the collapse of the panopticon scheme, while Anne Brunon-Ernst demonstrates the impact of the Plea in New South Wales itself, albeit via the mediation of Bentham’s good friend Samuel Romilly.

Providing an apparent contrast to this broadside against the legality of the New South Wales colony is the ‘Colonization Company Proposal’. Written late in life, it seemingly overturned many of the anti-colonial commitments of Bentham’s earlier works, not only on New South Wales, but more famously in his advice to the revolutionary French National Convention, only published in 1830 as Emancipate your Colonies! This has long been a creative conundrum in Bentham historiography: was there some underlying consistency between the apparent anti-colonial and pro-colonial Benthams, or some kind of abrupt conversion at the hands of zealous colonial reformers like Edward Gibbon Wakefield? Philip Schofield’s essay is firmly in the first camp; his nuanced account of the ‘Proposal’ and its vision of South Australia producing a dictator and ultimately becoming a self-governing, independent republic reconciles it carefully with earlier commitments.

Schofield highlights, however, another aspect of the ‘Proposal’ which haunts most of the other essays in this collection: the near complete absence in Bentham’s work of those indigenous peoples whose interests might be at stake in the establishment of a colony, whether comprising convicts or free settlers. It becomes impossible to square this silence with Bentham’s utilitarian premise that ‘each was to count for one and no one for more than one’, and so Schofield condemns the South Australian prospectus as ‘morally wrong’. This theme is most powerfully and systematically addressed in Zoe Laidlaw’s essay. She embraces the brief of examining the texts that comprise the critical edition, this time forensically interrogating their silences. Bentham’s silence on indigenous people is compounded by the skewed debate on Bentham’s colonial or anti-colonial credentials, which reinforced the key dynamic of settler colonialism: ‘erase the natives – or at least their sovereignty – and seize their land; seize the land and erase the natives’.

That a single volume of mostly unpublished work can elicit such a wide range of interventions is testament to the fertility of Bentham’s thought and the questions around criminal transportation, incarceration, settler colonialism and their legacies that it still prompts. Many of these legacies in the Australian context are potentially unsettling ones and it is to the credit of editors and contributors that these have been tackled head on. Certainly, when the bicentenary of his death rolls around, Bentham scholarship will be in rude health.

Comments powered by CComment