- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Museum life

- Article Subtitle: A thoughtful illumination of a complex man

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Australian Museum is starting to develop something of a literary landscape of its own. This is not so much through official publications such as Ronald Strahan’s Rare and Curious Specimens (1979) or the flagship magazine in its various incarnations from Australian Natural History to Explore. Rather, it is through more creative or expansive stories of the weird, wonderful, and personable, from Tim Flannery’s amusingly fictionalised historical recounting of The Mystery of the Venus Island Fetish (2014) to James Bradley’s disturbing future fiction The Deep Field (1999). Museum spaces – front and back of house – have an intriguing capacity to inspire and document their own strange and evolving histories.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Danielle Clode reviews 'The Naturalist: The remarkable life of Allan Riverstone McCulloch' by Brendan Atkins

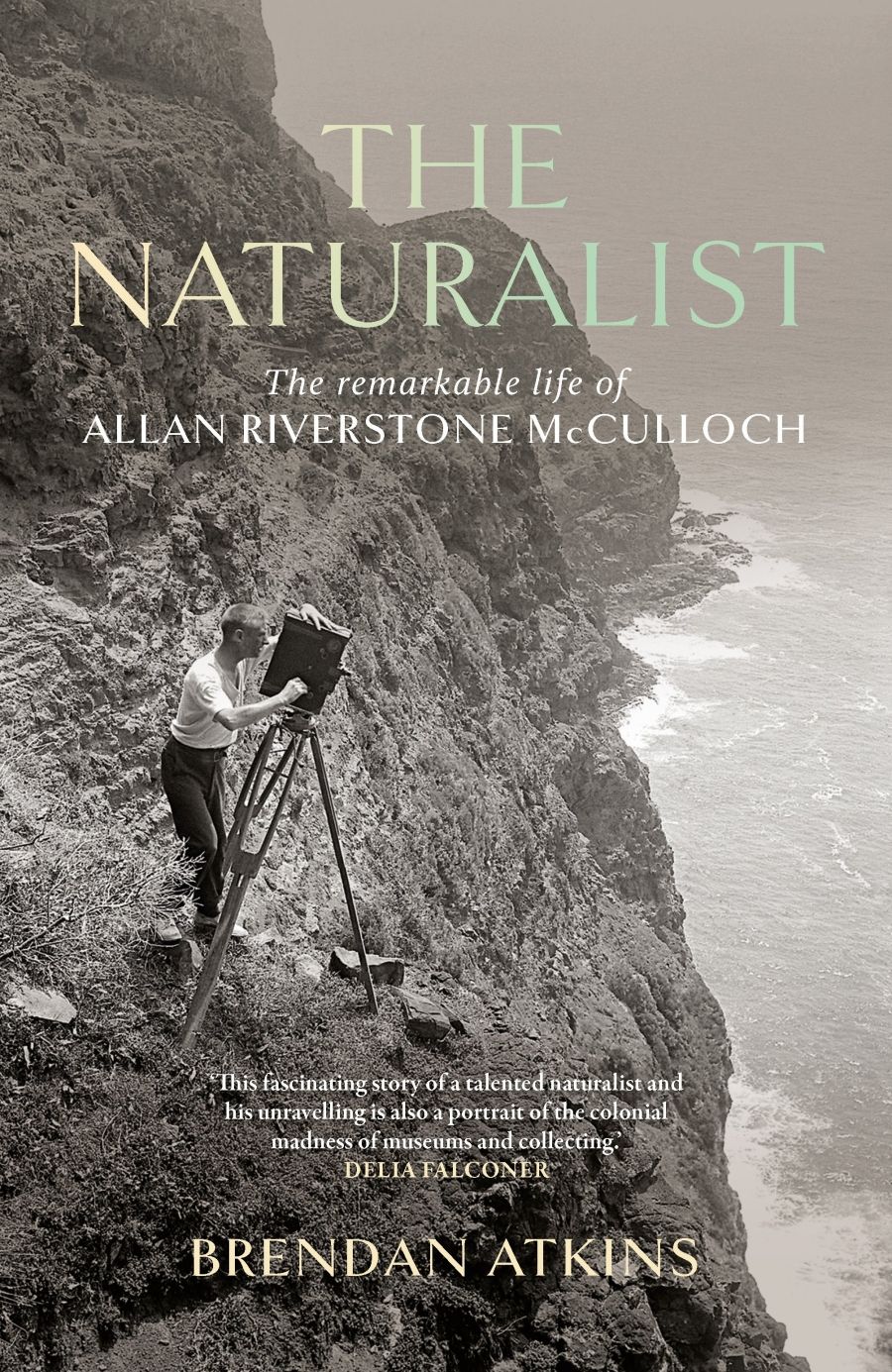

- Book 1 Title: The Naturalist

- Book 1 Subtitle: The remarkable life of Allan Riverstone McCulloch

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $34.99 pb, 198 pp

The life and work of McCulloch offers just such a nuanced and complex exploration of museum life. Born in 1885 and apprenticed as an unpaid cadet at the age of twelve, McCulloch trained in fish taxonomy and scientific illustration and became a world authority on Australian fish, a talented artist and exhibition designer, and a skilled science communicator pioneering the use of photography, cinematography, and radio. Yet these achievements, as Atkins notes, are rarely acknowledged in official histories.

Brendan Atkins’s account of McCulloch’s life and career bravely eschews the standard chronological approach of biography for a more thematic approach. While this does result in some repetition and backtracking, it has the effect of a gradual layering of the story, like successive work on a painting, adding light and shade, detail and perspective, gradually bringing the subject into focus.

In truth, while McCulloch’s museum position provides the impetus for this biography, it is not his office nameplate or even his scientific work that is the most interesting part of his life. McCulloch’s work seems to have progressed in spite of the bureaucratic constraints and challenges of the museum, or more particularly its trustees. Boards, it seems, have ever been stacked with members whose main qualifications would appear to be the size of their bank accounts and their connections, rather than their expertise or commitment to the core goals of the institutions they meddle in.

While McCulloch’s life in Sydney fills in some important gaps and new perspectives in the museum’s history, with some intriguing side notes into the local art scene, the book really starts to shine when McCulloch leaves the labyrinthine politics of the institution that employs him and escapes into the field.

The contrast between ‘museum McCulloch’ and ‘field McCulloch’ is dramatic. At the museum he seems to exist in a troubled world, constrained by poor finances, burdened by work and family, and often ill. In the field, he emerges into the bright, invigorating nature-filled light of Lord Howe Island, Papua New Guinea, and, finally, Hawaii. Rather than the erratic tempestuous man depicted by his more famed successor, Gilbert White, McCulloch in the field is described as good-natured, capable, hard-working, resilient, and well-liked. The field clearly suits him, as scientist, artist, and person, far better than the office.

Lord Howe Island is clearly a place of refuge and restoration for McCulloch – understandable given its spectacular scenery, equitable climate, and amazing wildlife. It is a true ‘naturalist’s paradise’, as he termed it, though not without its problems, with McCulloch documenting the devastation wrought by introduced rats. McCulloch would no doubt be delighted to learn that following the successful eradication of feral cats, pigs, and goats on the island in the 1980s and 1990s, rodent eradication programs are also proceeding successfully, with tangible environmental benefits.

McCulloch’s expeditions to Papua New Guinea with Frank Hurley were naturally more challenging. Here the line between research, private adventure, and public entertainment blurs and buckles. Hurley’s goal was to create dramatic photographic and documentary images of a land and people little known in Western society. McCulloch’s role was to collect cultural artefacts and natural history specimens for the museum. The challenges of collecting and preserving natural history specimens in a tropical environment are extreme. Cultural artefacts are often more durable, but the means of acquiring them can involve highly questionable practices of cultural theft and misappropriation. This remains an issue for the repatriation of museum collections today.

Atkins’s biography of McCulloch does not shy away from the darker aspects of his subject but provides thoughtful and considered illumination of a complex life that contributed much to our understanding of Australia’s fish, in particular, and the natural world of the Australasian region. Museum exhibitions, with their combined educative and entertainment function, are backed not only by decades of research and collections but also by the personal stories of the people who created them. We are all the richer for having a better insight into all the shades of this one.

Comments powered by CComment