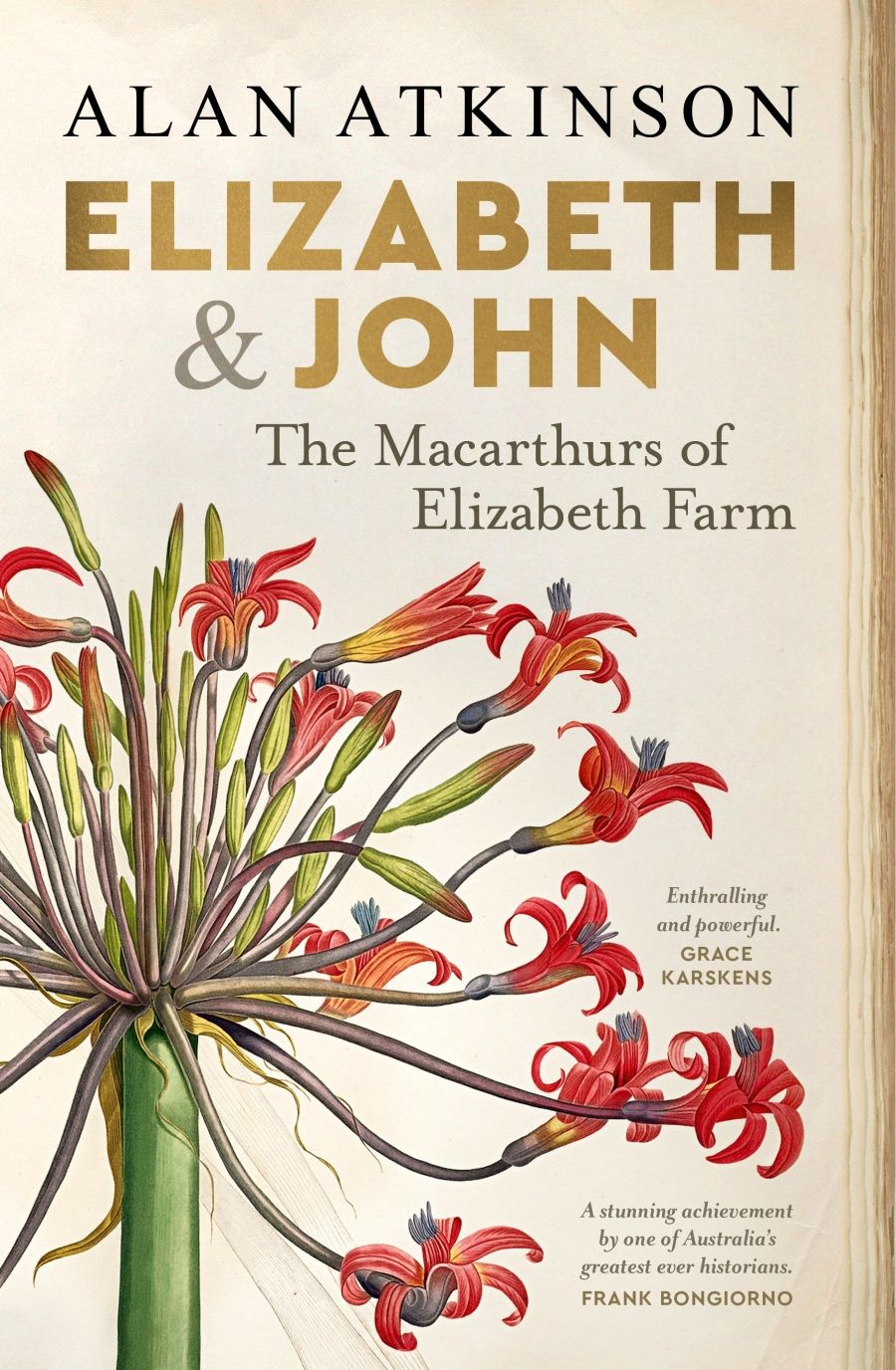

'If we take it for granted that John Macarthur was a bad man,’ writes Alan Atkinson, ‘then all the surviving evidence takes on a colouring to match. If we think that, then every word he wrote is suspect. On the other hand, leave the question of character open and the evidence takes on a new richness altogether – a deeper and more complex humanity. That is what I aim to do in this book.’

It is a bold undertaking in the present age, which seems reluctant to approach too near the flawed complexity of our colonial antecedents, acknowledge grandeur of design alongside selfishness of outlook, or understand the conviction of right among those we have convicted of wrong. It is a particularly bold undertaking in the case of John Macarthur (1767–1834), whose character seems fixed in popular understanding as a villain of the deepest dye. He has been the man we love to hate for so long that it seems impossible that there should be another side to the story. Restive, touchy, and imperious, he has figured as a profiteer, plutocrat, and thorn in the side of successive governors. Where trouble brewed, Macarthur was always there. In his own day, he sparked resentment and reproof. In the historiography of the past half-century, informed by labour, feminist, and settler-colonial critiques, his personal shortcomings are exacerbated by what he represents. As Australia’s earliest and most successful capitalist, and one of the most extensive landholders of the early nineteenth century, he profited from and was inescapably complicit in the violent dispossession and genocide that made that land available. Since his reputation for founding the wool industry is said to have rested upon the unacknowledged industry and influence of his wife Elizabeth (1766–1850), he is also the object of feminist scorn.

Without disputing their moral force, Atkinson asks us to set such familiar critiques to one side and see the Macarthurs afresh: to understand rather than judge, and where understanding seems impossible, at least to listen. He points out that most of the charges against Macarthur rest on thin documentary evidence, depending instead on myth and popular narrative. He promises to ‘take everything back to the beginning, so as to start inquiry afresh’. His raw materials are drawn chiefly from the startlingly rich archive generated by the Macarthurs themselves. Under his guidance, we ‘wander’ in the ‘great forest of voices’ they created and preserved. It is an archive with which Atkinson is uniquely familiar, for he has returned to it again and again through fifty years of history-making. On the strength of this unrivalled authority, he sets out to reconsider ‘everything we think we know’ about the Macarthurs’ lives – and in so doing to reconceptualise also the ‘larger story of British occupation and settlement’ during their lifetime.

This absorbing dual biography gives us John and Elizabeth Macarthur as they saw themselves. Atkinson observes them as they defined and defended themselves, and uses their words to write a history from their point of view, a history that turns what we think we know ‘upside-down – or rather, inside-out’. At the same time, he reminds us that the very quality of self-awareness, the capacity for introspection, was ‘one of the central achievements of the European Enlightenment’. John and Elizabeth, says Atkinson, were adept in ‘self-awareness, self-assessment and self-dramatisation’, and in this they were, both of them, products of their historical moment.

There are no quick answers here, no pithy summaries of argument, no shortcuts or headlines to draw attention to the book’s multiple acts of revision. It demands an immersive reading, a slow relaxation into multiple complex stories that recede and return, shaping the contours of an unfamiliar world. From page one, Atkinson launches us upon a discursive journey, confident that readers will share his joy in uncovering the ‘life of the mind’. Following multiple entwined pathways, we explore the world of words that helped to form the thinking of both Elizabeth and John. We catch the notes of intimate familiarity, the echoes of public discourse, the persuasive influence of friends – and, as a muted backdrop, the simmering hostility of detractors.

While he acknowledges the partiality (in both senses) of his sources, Atkinson rarely allows critique or doubt to disrupt his narrative. He lures you into a world-according-to-the-Macarthurs, and encourages you to believe in it. The Macarthurs’ own truth, filtered through Atkinson’s understanding, is rarely subjected to contrasting points of view. Their (or more accurately, John’s) self-justifications ride supreme above any counter-evidence of the effects of their actions or the – sometimes outraged – responses that they elicited at the time.

Elizabeth and John: the title of this shared biography promises to give Elizabeth at least equal billing with her more celebrated husband, and Atkinson struggles conscientiously to deliver on that promise, although the gender order of the day is against him. Consistent with his method throughout, he does not do so by claiming for her a greater significance than she claimed for herself. Elizabeth’s reputation as a pioneer in the Australian wool industry rests primarily on the fact that John was absent from the colony for years at a time – years in which his flocks grew and multiplied, the quality of their fleece improved, and exports increased exponentially in value. Atkinson makes clear that John’s absence from home did not leave his acres and flocks in exclusively female hands. He reminds us that while Elizabeth’s intellect and capacity for order may have matched and even surpassed John’s, her education and ambition did not. Hers may have been the ordering mind behind the first samples of fleeces sent to England, but John’s contacts and conversations while abroad soon saw his vision expand beyond hers. Elizabeth saw the ‘natural advantages’ of soil and climate with a keener awareness than John, but it was he who ‘took their story to a larger circle’, setting the horizon ‘alight with possibilities’. John’s stories were global, Elizabeth’s were local and domestic – and in this she provided an anchor for his restless soul. Atkinson’s efforts to present her as an equal partner cannot entirely withstand the weight of a sensibility that sees her bounded by familial concerns: less cosmopolitan than her husband, less political, less educated, less familiar with double-entry bookkeeping.

Elizabeth remains, to this reader at least, a subordinate presence in the book. Is this the fault of the historian or the history? Both she and John, one can’t but feel, would be astonished to see her getting as equal a billing as she does here. To do her more justice would require the employment of a different set of scales. Perhaps it is not possible to assess the nature (let alone the equity) of a marriage partnership without taking a step back – or several steps back – from how the partners themselves understood it, so as to analyse the power dynamics in play. Atkinson chooses instead to step forward, leaning in to catch each whispered thought, to sketch the relationship from inside-out – or, since that is essentially impossible, at least from the partial perspective of a sympathetic eavesdropper.

There is a fugitive pleasure in thus being invited to sit beside the Macarthurs – to appreciate John’s quickness of perception and loftiness of purpose, and share his hopes and disappointments through twists and reversals of fortune. There is a pleasurable poignancy to wincing in sympathy at the wrenching, repeated separations that dogged their family life: husband from wife, children from mother, sister from brothers. But Atkinson hopes that his readers will not confuse understanding with endorsement, commenting at the outset that it is ‘very hard to enter thoroughly into someone else’s world view without at least seeming to take their side’. That ‘at least’ speaks volumes.

Atkinson points the path to critical scepticism, but only intermittently walks it. He writes in two registers: on the one hand extolling, in elevated prose, the romantic promise of the Enlightenment as it drove ‘technological progress, material prosperity, emotional sensibility and cultural refinement’; on the other acknowledging, in disruptive interjections, the structural inequalities of gender, class, and race on which that progress depended. While marriage was the ‘way forward’, for the young Elizabeth as for all girls, its promise was ‘deeply misleading’. While trust lay at the heart of John Macarthur’s vision for an ordered, hierarchical society, trust ‘could not exist between the officers and the suffering poor’. And in the convict settlement of New South Wales, ‘entitlement and violence had been there from the beginning. That was what invasion meant’.

If such sentences – the examples could be multiplied – seem to puncture the insular vision of the Macarthurs, the flow of narrative invariably restores it. Thus Atkinson builds a kind of doubled historical awareness: sympathy and scepticism held in imperfect balance. Critique sends a seeping chill around the edges of a narrative warmed at its heart by a firm belief in the virtues of trust, justice, affection, and improvement. Atkinson’s belief, or the Macarthurs? It is sometimes hard to tell, but the congruence of values between author and subject ensures that, in this book, sympathy will always win the day.