- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Stately, plump Buck Mulligan’

- Article Subtitle: The long and arduous Joycean adventure

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Earlier this year, I took a group of students to the State Library of Victoria (SLV) to see its impressive Joyce collection. We examined some special books, including lavish editions of Ulysses: the 1935 Limited Editions Club edition, with Matisse’s accompanying etchings; the 1988 Arion Press edition, with illustrations by Robert Motherwell – and various others. But the one that had lured us down Swanston Street was the iconic first edition, with its famous blue cover, fortuitously acquired by the SLV in 1922.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Ronan McDonald reviews 'The Cambridge Centenary Ulysses: The 1922 text with essays and notes' by James Joyce, edited by Catherine Flynn

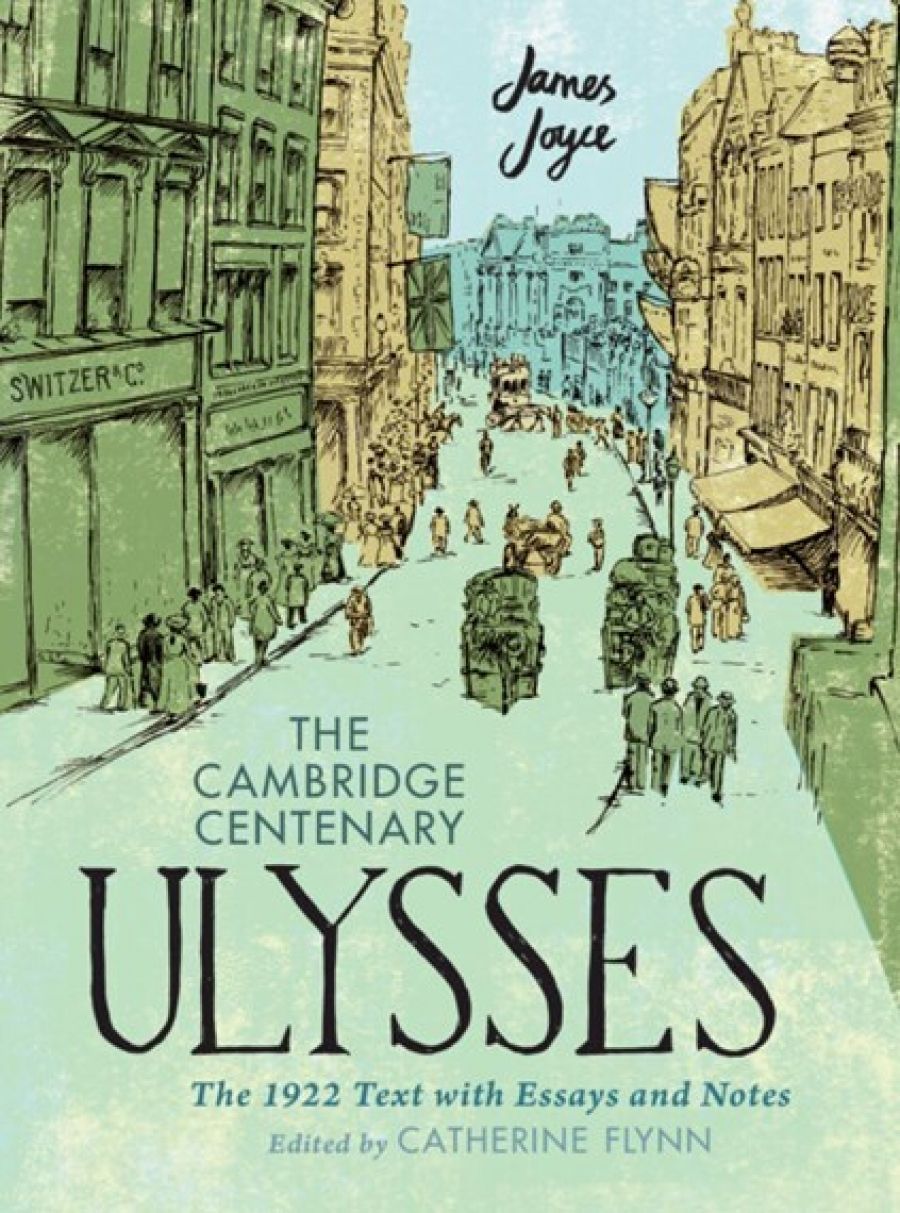

- Book 1 Title: The Cambridge Centenary Ulysses

- Book 1 Subtitle: The 1922 text with essays and notes

- Book 1 Biblio: Cambridge University Press, $56.95 hb, 988 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/the-cambridge-centenary-ulysses-james-joyce/book/9781316515945.html

Flynn justifies using the first edition on the basis that, if some errors are reproduced, at least it is free of the many later, erroneous attempts to ‘clean up’ the text. Beginning with Joyce’s own errata notes, which are helpfully reproduced in the margins here, Ulysses has been subjected to, and often suffered from, well-intentioned proofreaders and typesetters ‘correcting’ errors. If hundreds of mistakes were picked up, numerous new variants were introduced in later versions. We are still without a definitive version.

The closest scholarship has come to that ideal is Hans Walter Gabler’s Ulysses: A critical and synoptic edition (1984), the first to make use of computer technology and meticulously comb through all of Joyce’s manuscripts and drafts. That edition was itself prominently excoriated by the academic John Kidd, who famously wrote about the ‘scandal’ of Ulysses in the New York Review of Books (8 June 1988). Nonetheless, Gabler’s has become the most commonly cited edition in Joyce scholarship. This Cambridge Centenary edition includes the line numbers from Gabler in the margins, allowing readers to follow the extensive Joyce scholarship. It also indicates Gabler’s most important interventions in the footnotes.

In a compressed but effective way, this new edition both starts at the beginning of the story of Ulysses’s publication and gives the reader a sense of the textual history of the novel. This is one of several features that make Cambridge Centenary Ulysses a hospitable experience for readers, new and old, and scotches any presumption one might have that it is destined to be a dust-gathering collector’s item. The book’s dedication is ‘For the reader, setting off on a long and arduous adventure’, and the textual apparatus delivered here does much to aid that notional Homer. It includes a wealth of illustrations, maps to locate chapters and trace characters’ movements, black and white photographs of Dublin, a chronology of Joyce’s life alongside contemporaneous cultural and political events, an index of recurrent characters, reproductions of Joyce’s schema, and extensive guides to further reading. That’s not to mention the helpful annotations at the end of every page and the introductory essays, provided by Joyce scholars and preceding each of the eighteen episodes that make up the novel.

How much annotation do we need when approaching Ulysses for the first time? Arguably, we should be less frantic about chasing down allusions and references in Ulysses in our digital era – they are readily accessible not only in the long-established guides and annotated editions but in the ever-expanding online resources, glossaries and podcasts (like the late Frank Delaney’s Re-Joyce podcast).One of the reasons why readers are waylaid in Ulysses is because they approach the novel with a grim determination to unlock it, to chase every allusion, or to gloss every reference. But to experience Ulysses is not to master it – indeed the latter might stymie the reading experience. As readers, we do well to approach the novel with negative capability, to borrow Keats’s term; to rest in uncertainty and obscurity; to settle for knowing some allusions and not others; to sit in the half-light of partial understanding, such that we not only read the text but become aware of ourselves as implicated within the meaning-making process. This edition calmly and neatly offers selective annotations and explanation in smaller type at the foot of the page, so that it does not overwhelm the text. It does not pretend to dispel every obscurity and opacity. Nor does it threaten the fluency and flow. Like much else here, the aim is to provide supportive information while smoothing the literary journey.

To offer readers individual introductory essays on the eighteen episodes of Ulysses is not unprecedented. All here are written by experienced and informed scholars who, crucially, can write for a general audience, and their reflections click together satisfyingly. Each one analyses how Homer’s Odyssey informs the relevant episode (thus unlocking the title) and situates that analysis in relation to the one before and after, while also offering fresh and arresting insights and interpretations. These scholars also feature in the ‘U22: The Centenary Ulysses Podcast’, which has been released at intervals to accompany the edition and which includes absorbing conversations with readers of the novel from all sorts of backgrounds, including one or two Australians whom I was surprised to encounter. We test our students’ spinal tolerance at our peril, but despite the book’s weight I plan to assign this edition as the required edition for my Honours Ulysses class next year. That surely counts as high recommendation. You could do worse than put the Cambridge Centenary Ulysses in a few Christmas stockings (but make sure they are extra wide).

One Hundred Years of James Joyce’s Ulysses will interest those who want to dig further into the materiality of Joyce’s great work: into the book as object, how it comes to exist, both bibliographically and historically. Published to accompany a centenary exhibition, which has just concluded at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York, the book is lavishly visual, as you would expect. Here you can see colour photos of some of the additions and emendations that Joyce made to the proofs he sent back to the Dijon printers, as well as extracts from autograph manuscripts, including ‘Stately, plump, Buck Mulligan’ in Joyce’s own spidery hand. The exhibition was curated by the Irish writer Colm Tóibín, who edits this volume and writes an essay marked by his style of anecdote-rich literary history. Tóibín is currently doing a sterling job as the Laureate for Irish Fiction (how about an Australian version of that ambassadorial role?), which may be one reason why the poet and president of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins, writes a short preface for the exhibition, reproduced here.

There are ten other essays, including one by the legendary book dealer Rick Gekoski on the astonishing ‘Sean and Mary Kelly Collection’, donated to the Morgan by the British-born art gallerist Sean Kelly (‘a born James Joyce collector’). There is also an interview with Kelly by Tóibín, a couple of essays on US holdings of Joyce-related archival materials, and a series of essays (including one by Catherine Flynn) on Joyce and the various cities with which he is associated (Dublin, Trieste, Zurich, Paris). A more detailed account than I have provided above of the travails of Joyce’s publication and his battles with the censors is presented in illuminating essays by Maria DiBattista and Joseph M. Hassett.

Joyce notoriously predicted that his great book would ‘keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that’s the only way of insuring one’s immortality’. One century down, Joyce shows no signs of mortality yet.

Comments powered by CComment