- Free Article: Yes

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Dismantled lives

- Article Subtitle: Gail Jones’s elegant new novel

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1917, at the height of World War I, a fire destroyed the Greek city of Salonika (Thessaloniki), a staging post for Allied troops. The centre of an ‘Ottoman polyglot culture’, Salonika was at the time home to large numbers of refugees, many of them Jewish and Roma. It was in one of the refugee hovels that the fire started, an ember from a makeshift stove igniting a bundle of straw. From that single ember grew an inferno that burned for thirty-two hours, obliterating three-quarters of the city and leaving 70,000 people – by some estimates half the population – homeless.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Diane Stubbings reviews 'Salonika Burning' by Gail Jones

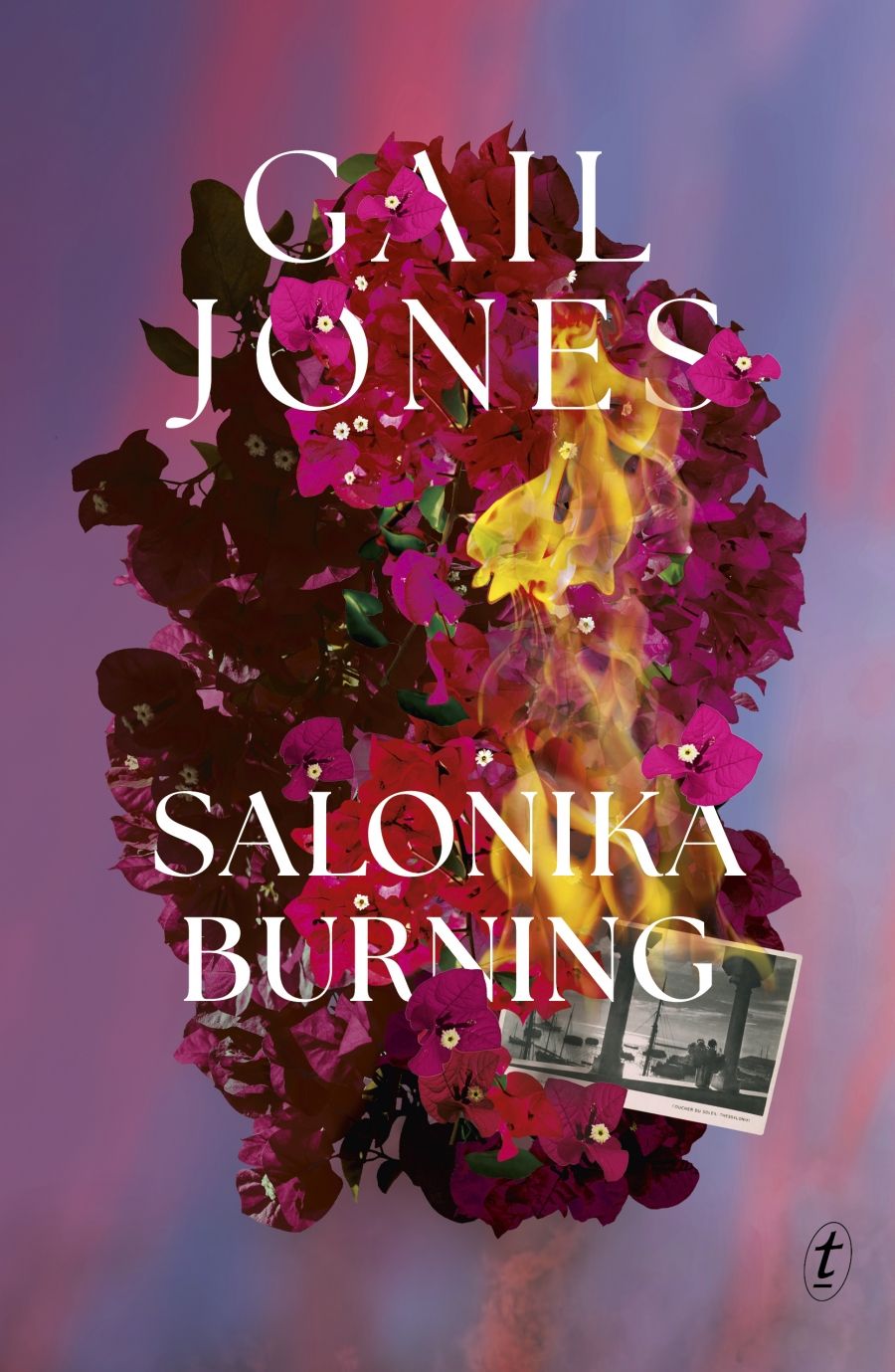

- Book 1 Title: Salonika Burning

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $34.99 hb, 256 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/salonika-burning-gail-jones/book/9781922458834.html

Jones filters the fire – its ignition and its aftermath – through four voices, four sensibilities. Olive, a volunteer driver who has used her father’s money to convert an old lorry into an ambulance, sees within the fire a myth that might claim her: ‘She was falling like Icarus, transformed into a story.’ Stanley, an orderly transporting the wounded, watches ‘Salonika gleaming lovely before him, flashing its own demise’. He is ‘ashamed of his pleasure’. In the tents of the Scottish Women’s Hospital, surgeon Grace smells the lingering smoke of the fire, recalls the ‘vermillion glow like a welt on the horizon’. And in the kitchen, assistant cook and part-time orderly Stella is ‘sparked’ by the fire’s ‘implausible magnitude … [and] elemental destruction’.

What unites their perspectives is the disconcerting frisson of excitement the fire’s fury engenders within them. Each character seeks a new sense of stability, one that might counter the disequilibrium the fire has occasioned. Stanley finds stillness and certainty in the pages of his art books, in the ‘reassurance of familiar things’, while Stella ‘obscure[s] the ravage and idiocy and dreariness of it all’ by envisioning the journal articles and stories that will allow her to ‘write her way into other possibilities’. Olive attempts to ‘bring her feelings under control’ by arranging ‘matters in a human order’, reciting German grammar as a curb on her emotions. Grace focuses on the flesh and blood of the soldiers on whom she operates, refusing to again make ‘the mistake of imagining beyond the brute red stuff of the body’. However, they are each undone by evocations of the past. In attempting to apprehend their experience – to ‘be safely entrenched’ in a defining story that ‘assert[s] grid and location’ of the world and their place in it – they merely expose how the lines and borders by which they each define themselves are constantly slipping between shadow and illumination.

From the outset, Salonika Burning concerns itself with the ‘pretty lies of art’, how we assemble words and images into structures that offer an illusion of order and meaning, an illusion that is disturbed by the vibrations of memory. Memory manifests like ‘the splinters of another life showing in the flesh of a new wound’, and the effect is a present moment that is layered like a palimpsest, past and future integral facets, integral dimensions, of the same fragment of time: ‘The boundary between past and present, between outside and inside, was the barest quivering screen.’

What seems key to Jones’s purpose is that each of the central characters she portrays has their own biography, their own presence in the historical record: Stella Miles Franklin finds fame as a novelist, Olive King as an adventurer and philanthropist, Grace Pailthorpe as a surrealist painter, and Stanley Spencer as an artist. But Jones refuses to be bound by the way history has depicted these lives or to explain them in terms of ‘a baggage of ingenious, infuriating links, needing a narrative explanation’. Rather, she casts a smoke haze around these biographies, thus emphasising the blurred edges of selfhood that are a necessary consequence of being in a world that is, to borrow from the David Malouf quote Jones uses as an epigraph, ‘alive and dangerous’. In such a world we might construct a ‘distant map-in-the-head’ to steer our future steps, but in the end it ‘guide[s] nothing, signifie[s] nothing’, reminding us only of a ‘distant solid ideal’ that, like the planned rebuilding of Salonika, can never be wholly realised.

Salonika Burning’s four narratives overlap and intersect, a web-like pattern of images and common encounters – mirrors, songs, light, a stagnant lake, a child with an ikon, the flesh of a skinned rabbit, an injured German soldier – holding them together. As Stanley envisages when thinking of his own art, the ‘arrangements of space between people and their angle of inclination, like the fixed and moving prongs of a drawing compass, were enough to reveal divine circles and implied connections’.

What Jones reveals through these four distinct voices is the way discrete acts of witnessing converge and then diverge again – that there are not so much different truths but rather a single truth that acquires different bands and hues as it is refracted through individual experience and memory. The fascination for Jones is not the cast of ‘truth’ that emerges – whether represented within images, stories, biographies, or myths – but the processes by which that ‘truth’ is composed.

Jones’s language in Salonika Burning is at once muscular and delicate, her narrative precise yet impressionistic, neatly echoing the themes she is probing. Stanley, for example, imagines the ‘human body … the rupture of perspective such as a tall mirror might provide in which planes were reversed and images duplicated, or multiplied, or made distant and uncertain’. Similarly, Grace is overwhelmed by memories of swimming in the sea for the first time: ‘Shingles loosened beneath her toes. Light reached in shafts to her pallid feet. The tide rippled in and surface sheen parted and lapped around her … The sense of being held inside a larger organism.’

The ever-shifting nature of self, and our deployment of stories – about ourselves and the world-at-large – to ‘find [our] outlines again’, are familiar themes in Jones’s work but never more comprehensively nor artfully rendered than they are here. The cumulative effect of enclosing these fervid sensibilities within the same geographical limits – and at some distance from the ‘great and awful unmaking’ of the war’s frontline – and then exposing them to the existential heat of a fire that might ‘consume them all’ serves to sharpen and concentrate Jones’s preoccupation with the way we construct meaning, as storytellers, artists, and human beings,

in order to bring our ‘dismantled lives … back into recognition’.

Gail Jones has written some fine novels – Sixty Lights (2004), Sorry (2007), and A Guide to Berlin (2015) among them – but none finer than Salonika Burning.

Comments powered by CComment