- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The crunch of broken lives

- Article Subtitle: A forensic, unflinching, yet diffident history

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Armando Iannucci, creator of the darkly comic series Veep and The Thick of It, is surely one of our more perceptive contemporary political observers. While making us laugh or grimace with recognition at the manoeuvrings of his characters, he can also pull us up cold. For example, Iannucci spends most of The Death of Stalin mocking the posturing of the politburo following the tyrant’s death in 1953. Then, suddenly, disturbingly, the merry-go-round judders to a halt and Beria is ambushed, tried, and executed in a courtyard. It echoes the mockery of the shirtless and mounted Vladimir Putin – before he invaded Ukraine

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

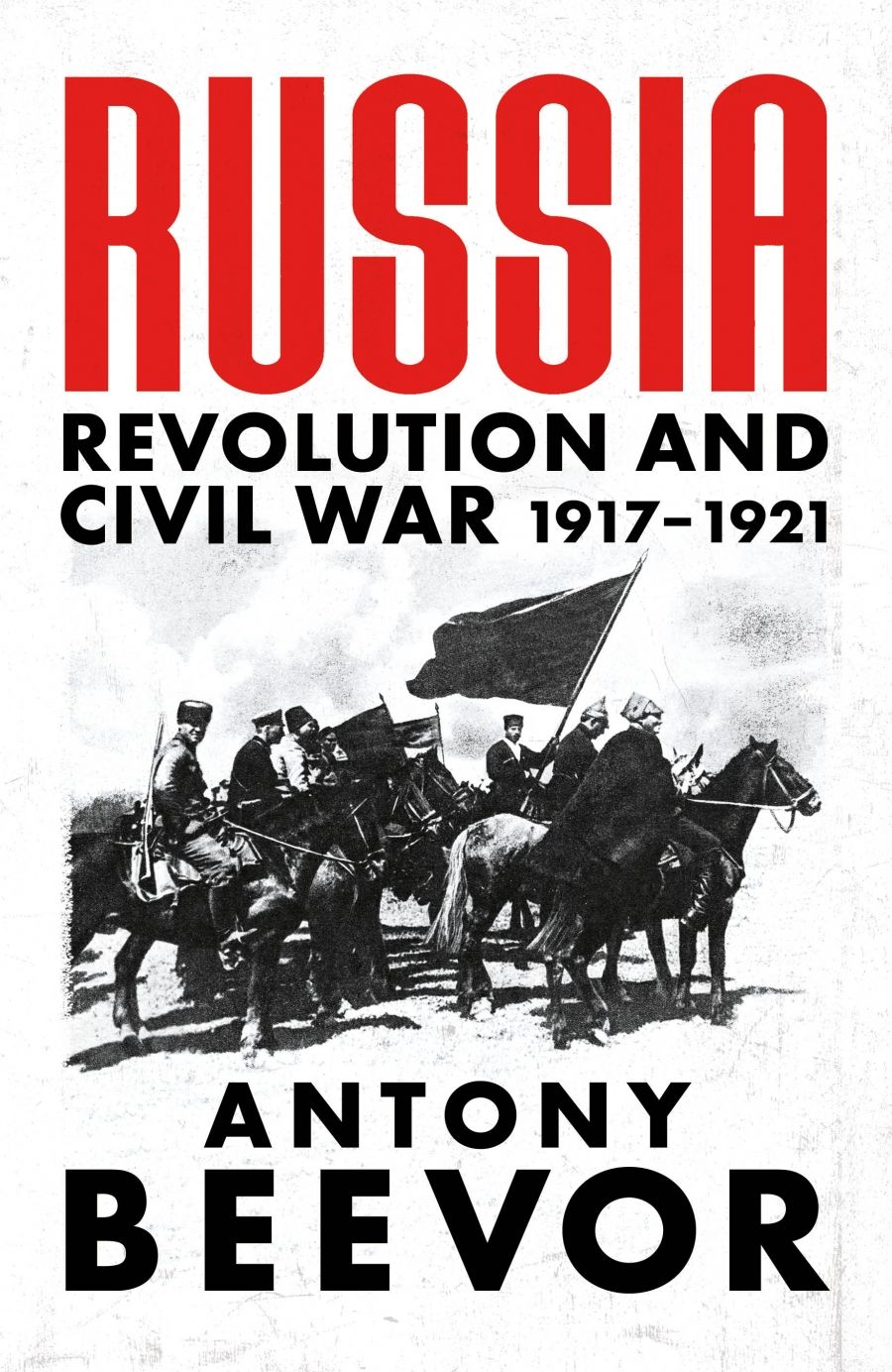

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Tim McMinn reviews 'Russia: Revolution and civil war 1917–1921' by Antony Beevor

- Book 1 Title: Russia

- Book 1 Subtitle: Revolution and civil war 1917–1921

- Book 1 Biblio: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, $55 hb, 589 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/russia-antony-beevor/book/9781474610148.html

The work is in the mould of Beevor’s classic histories Stalingrad (1998) and Berlin: The downfall 1945 (2002). However, his ambition, in Russia, is even greater; the scope so much more multifaceted, tackling a longer time period, with substantially more political and less military history than either of those works. As always, Beevor’s work draws on rigorous archival research. He is still liable for five years imprisonment in Russia for Berlin’s documentation of the mass rape of German women by the Red Army. At times I wondered how he managed to write this book. The answer lies in the dedication to Lyuba Vinogradova, Beevor’s ‘partner in history’. Without her tireless work and ‘inspired selection of material’, he admits it wouldn’t have been conceivable.

The Beevor treatment is all there in Russia. The first couple of hundred pages recount the rise of the Bolsheviks and the intricate factional manoeuvrings in St Petersburg. The latter sections shift focus to the unceasing movement of frontlines and battle scenes. Beevor intermittently nods towards the violence occurring behind the lines – the Red Terror (he devotes a brief chapter to this) and pogroms launched by White Russians – but he declines to plumb the depths of these hatreds.

There is nothing banal about much of the evil told at the margins of this history. Beevor chillingly quotes the poem of an executioner from the Cheka (the first Soviet secret police organisation): ‘there is no greater joy, nor better music / Than the crunch of broken lives and bones.’ This quote – and other descriptions of terrible violence – calls to mind Vasily Grossman’s description of the ‘fiend in human shape’ at Treblinka who would scream at his victims as they were led to their murder, ‘your bath water is cooling. Schneller, Kinder, schneller!’ (The Years of War, 1946).

Such horror demands an explanation, or an attempt at one. Russia’s mere one-and-a-half pages of conclusion just aren’t up to this task. In Beevor’s summary, civil wars are ‘bound to be cruel’, and while ‘the Whites represented the worst examples of humanity’, for ‘ruthless inhumanity, the Bolsheviks were unbeatable’. On the last page we learn that the civil war was responsible for the loss of up to twelve million lives. History should help us make sense of the past, but for a general reader these statements explain little.

Beevor might reply that ‘the echoes and rhymes of history are beguiling, but history is not going to tell us about the future’, as he did in an interview for BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs in 2017. He resists the widespread tendency to draw pat lessons from history and leaves it up to us to make something of the exhaustive research that he (and Vinogradova) lays before us.

Timothy Snyder is a historian taking a different approach as he strives to help us to understand the most terrible period of history in Eastern Europe, when fourteen million people were deliberately killed between 1933 and 1945. Beevor described Snyder’s penetrating work Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin (2010) as ‘one of the most important [books] to emerge for a long time’.

The bloodlands encompass the lands most touched by the Nazi and Stalinist regimes – the western rim of the Russian Federation, most of Poland, the Baltic States, Belarus, and Ukraine. They also overlap the western and southern fronts of the civil war. Snyder’s history starts eleven years after Beevor’s ends. Hitler’s colonial vision of Lebensraum (or ‘living space’) in Ukraine was inspired by the brief period of German occupation there in 1918. Stalin fought there during the civil war and formed a similar view. Imperial designs on Ukraine’s chernozem (or black earth) remain alive and well with Putin’s invasion. For an admirer of Snyder’s work, it seems remiss that Beevor has done so little to explain how the civil war and its violence behind the lines echoed through the twentieth century.

Snyder’s searching essay ‘Humanity’ at the end of Bloodlands is what history should strive to be. He recalls the voices of those who lived; draws on Hannah Arendt and Grossman to identify the denial of ‘groups of human beings of their right to be regarded as human’ as the common thread through Nazism and Stalinism; and challenges our temptation to identify with the victims of violence, reminding us that Hitler and Stalin both claimed throughout their political careers to be victims. Attempting to understand the perpetrators is what Snyder believes his history must do.

Berlin opens with the lamentation of Albert Speer to his captors that ‘history always emphasises terminal events’. On the contrary, Beevor argues: the final stages of a regime’s downfall are its most telling. Stalingrad and Berlin came alive because Beevor captured central historical instants of turning, of termination, and packed them with incredibly researched detail. They were freighted with immediacy by the voices of everyday people who lived and died during these events. He bears the standard of Grossman’s tradition in this respect. In Snyder’s words, ‘Grossman extracted the victims from the cacophony of a century and made their voices audible within the unending polemic’. Beevor at his best does just this, striving to shift our focus from numbering the dead to naming those who lived.

Perhaps my issue with Russia is that a revolution preceded by a world war and followed immediately by protracted civil war is not a terminal event or turning point in the same sense as the Battle of Stalingrad or the fall of Berlin. Such a period requires more interpretative work alongside the concatenation of events. Russia seems to lack the volume of direct source material from the street and trench level in these years. It may be that these voices are just not as accessible during this period as they were later in the twentieth century.

In his acknowledgments, Beevor tells us that Russia is a book he has been longing to write since he had to reluctantly abandon his first attempt more than thirty years ago. Yet he has probably applied the military history formula of his intervening blockbusters somewhat too rigidly for a subject of this scope. You learn a great deal reading this sweeping work, though you should have Google and Wikipedia beside you. To fully understand these events and the shockwaves they caused, you may need to consult some other books.

Comments powered by CComment