- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

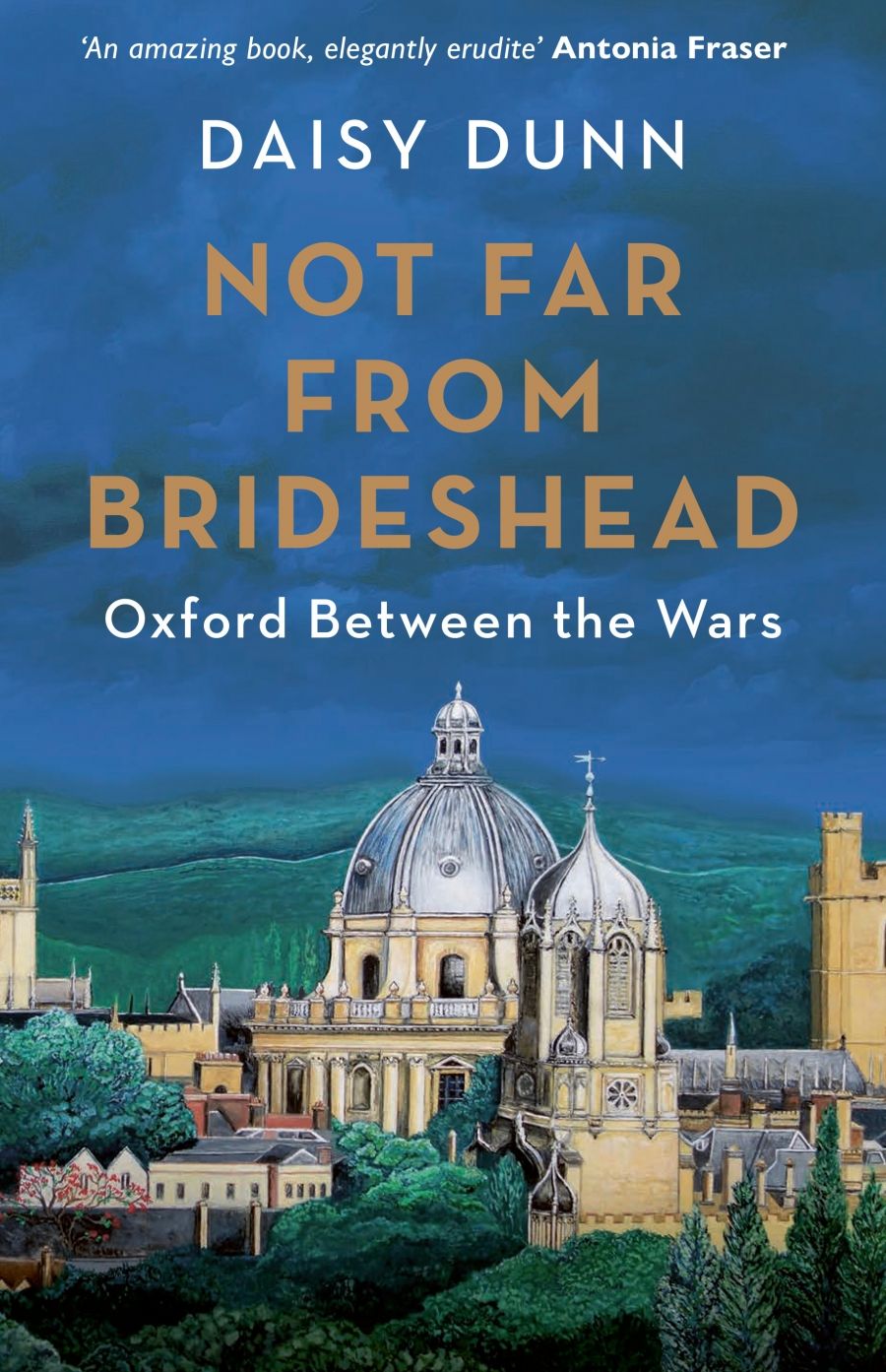

- Article Title: 'What a piece of artistry'

- Article Subtitle: A study of interwar Oxford

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Oxford is not what it was once. We scholars swot too hard. Even the Bullingdon has lost its brio. It’s hardly surprising that this Age of Hooper has ushered in a cottage industry of aesthetes’ nostalgia, for many sense that the time when students could still be boys, and boys could be Sebastian Flyte, was just more fun. No reports, recorded lectures, or Research Assessment Exercises to interrupt the heady days of evensong, buggery, and cocktails (to paraphrase Maurice Bowra’s infamous utterance).

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Miles Pattenden reviews 'Not Far from Brideshead: Oxford between the Wars' by Daisy Dunn

- Book 1 Title: Not Far from Brideshead

- Book 1 Subtitle: Oxford between the Wars

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette, $49.99 hb, 304 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/not-far-from-brideshead-daisy-dunn/book/9781474615570.html

Dunn’s book covers Oxford’s return to normality in the aftermath of 1918, the exuberance and excesses of the 1920s, and the darkening horizon of the 1930s. However, its true focus is the competition (unofficial, of course) to succeed Murray as Regius Professor of Greek in 1936. Murray was, in some ways, an unusual Oxonian figure. Born in Sydney in 1866, he had come to Britain with his widowed mother aged eleven and was a hypochondriac, vegetarian, and teetotaller. He married above himself: Lady Mary Howard, daughter of the ninth earl of Carlisle. Oxford was the place for an ambitious Antipodean to make it in those days – little ground in Britain was so fertile for a spot of social climbing. Murray excelled himself, above all, as a public figure and internationalist activist for the League of Nations. He was certainly also brilliant of mind and extraordinarily industrious of output. On the other hand, his disparaging query to guests when he served them the meat he felt obliged to provide (‘Will you have some of the corpse?’) smacks of boorish dogmatism. Murray’s explanation of his vegetarian ethos harked back to Australia. He was haunted by childhood memories of possums being shot out of trees, he said, whereupon they were devoured by ravenous dogs.

Bowra and Dodds could scarcely have been more different from Murray, for all their prominence in the race to succeed him. Witty and urbane, but also short, plump, and homosexual, Bowra is the better known of the two, but his scholarship was a little too slapdash for Murray’s tastes. Prominent posts such as Regius Professor were not decided through any charade of open competition in those days, of course. Rather, the appointment rested in the hands of the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin. However, in rushed circumstances, with the Abdication crisis surrounding Edward VIII rather more pressing, Baldwin relied almost entirely on the outgoing post-holder’s recommendation. Murray had initially submitted three names for him to consider: Bowra, J.D. Denniston, and Dodds. Denniston was a respected fellow of Hertford but seemed to lack the star quality which Bowra certainly had. Yet, in the end, Murray felt that he could not ‘in good conscience’ support Bowra’s elevation to pre-eminence either, having attended one of his lectures and encountered one too many of his intellectual infelicities.

Dodds became Murray’s choice then, although he was the choice of hardly anyone else in Oxford. The most brilliant translator of his generation he may have been, but he worked as much on English literature as classical. Moreover, his tastes in the latter – Proclus, Plotinus – were decidedly recherché. Far worse, Dodds, though Presbyterian in upbringing, was an Irish Nationalist who had been asked to leave Oxford in 1916 on account of his support for the Easter Rising. Dunn is not at her strongest in explaining why this was totally unacceptable to the dons or to the wider British establishment on whose patronage they depended back then. Dodds was ‘exiled’ to Birmingham – a fiery industrial Mordor, in Dunn’s language. This nod to Tolkien also seems a touch out of place, for Dodds was very much at home there. Certainly, far more than he was ever to be in Oxford’s benighted ‘Shire’, where his colleagues proved preternaturally rude towards him. Dodds’s eventual appointment to Oxford was nevertheless inspired: his books are still read today, unlike Bowra’s or Murray’s. Sadly, Bowra’s failure to secure the Chair devasted him, and even his historic, much fabled wardenship of Wadham College (1938–70) could not make up for the loss.

Where then is Brideshead in all this? The link in Dunn’s text is more impressionistic than substantive. Evelyn Waugh himself appears from time to time to provide colour, as do other Oxford luminaries of the era: T.S. Eliot, W.H. Auden, John Betjeman, Louis MacNeice, Anthony Powell, C.S. Lewis, Vera Brittain, Kenneth Clark, etc. Bowra himself was also supposedly the model for Waugh’s cruel caricature, the wretched, seedy Mr Samgrass. ‘I hope you spotted me,’ Bowra would brag: ‘What a piece of artistry that is.’ His true private feelings on Samgrass are unrecorded, yet his apparent magnanimity piqued Waugh, who had little time for senior academics. In some ways, Bowra’s reaction hints at the methodological difficulty of really grasping the historical essence of the personalities involved here. Dunn, an Oxford classicist rather than a historian, is a nimble and sophisticated guide – but she and all of us may still be excessively influenced by Waugh’s sepia tones.

Bowra himself thought Waugh’s rendition of 1920s Oxford ‘Brilliant! Brilliant! … Perhaps too brilliant!’, which may well have been an attempt to damn with praise. But, having missed out on this supposed Golden Era of Oxonian life, I read Dunn’s account of Bowra, in particular, with a sense of sadness and even exasperation. Bowra’s Times obituary proclaimed that ‘posterity will have no measure of his true greatness’, yet he comes across here as a pitiable, somewhat frustrated figure. Oxford has always been exquisitely calibrated to make gay boys from bourgeois backgrounds feel like eternal outsiders – a problem on which Dunn’s romanticised account does not really dwell. But condemned socially by snobbery and sexually by homophobia, Bowra’s was a life always striving – working harder than anyone else – to fit in with quite unpleasant people. We know little of his affairs: though not closeted, he was discreet. However, I suspect Dunn’s phrase that Berlin was ‘more to Bowra than a brothel’ is an exercise in sanitisation. In any case, if true, that makes it all the sadder. One can’t help but think he might have been more fulfilled, and his scholarship all the sounder, if he had grown up in the age of Grindr, PreP, and neoprene.

Comments powered by CComment