- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A vast canvas

- Article Subtitle: Bob Moore’s ambitious history of prisoners of war

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This is a difficult book to read, not because of its length (nearly 500 pages without references); nor because of its density. It is because this study of prisoners of war in Europe during World War II documents suffering on an almost unimaginable scale. In this theatre of war, more than twenty million servicemen and servicewomen fell into enemy hands. Millions did not survive captivity.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: A German prisoner of war is guarded by a Soviet soldier (from the book under review)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Joan Beaumont reviews 'Prisoners of War: Europe: 1939–1956' by Bob Moore

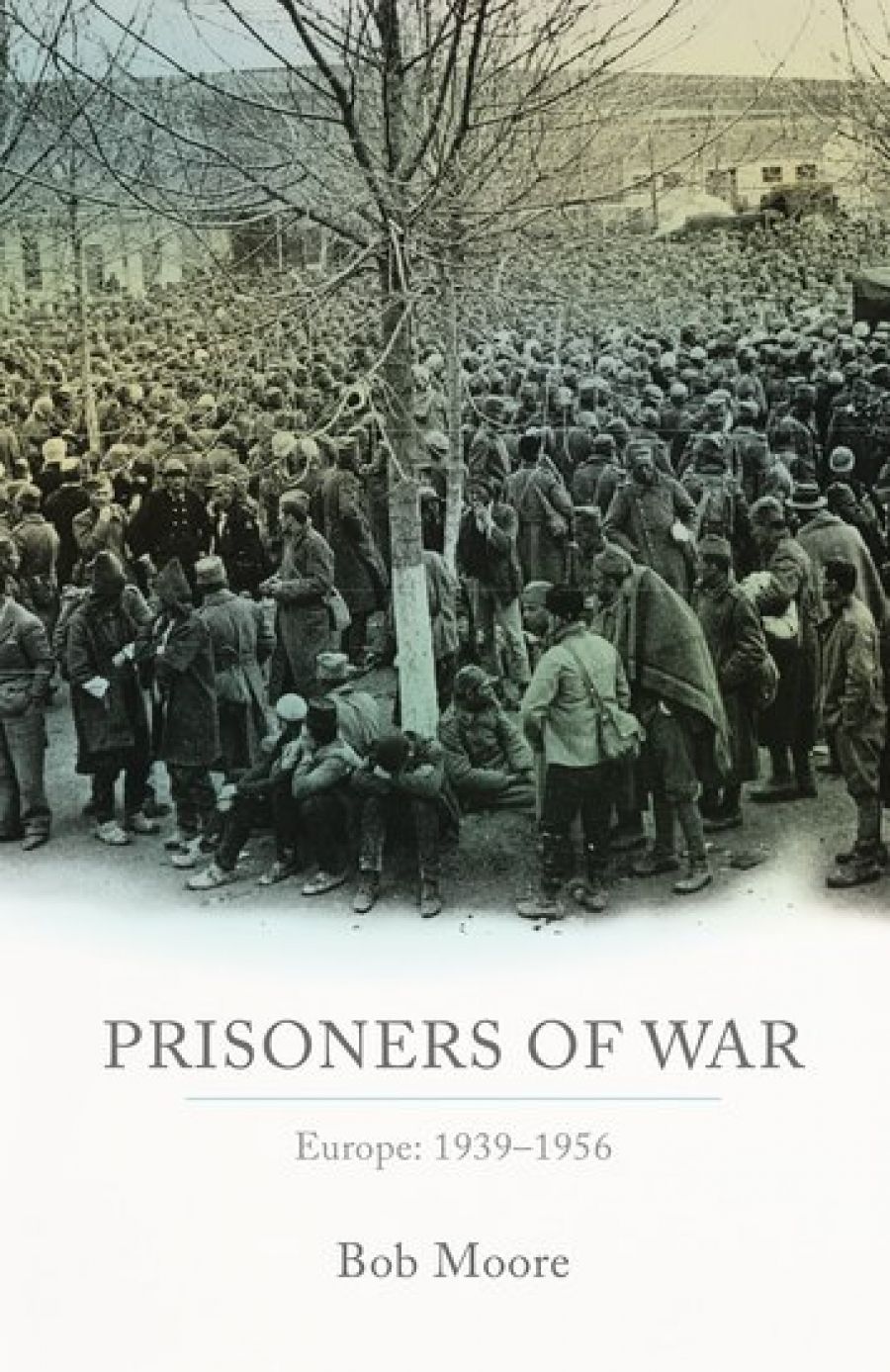

- Book 1 Title: Prisoners of War

- Book 1 Subtitle: Europe: 1939–1956

- Book 1 Biblio: Oxford University Press, £35 hb, 551 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/prisoners-of-war-europe-bob-moore/book/9780198840398.html

In Germany, Allied prisoners were at greater risk, especially in the last year of the war, when those in the path of the advancing Red Army were forced to march westwards in bitter winter conditions. Food was a constant concern, even for those POWs who were able to receive Red Cross parcels. Despite these hazards, and the tedium and psychological malaise that attended years of inactivity and anxiety about families at home, Allied prisoners were treated relatively well.

The key word is ‘relatively’. On the Eastern Front, the story of Soviet prisoners in German captivity is ‘a harrowing litany of unremitting suffering and death where only a minority survived to tell the tale’. The statistics are conflicting and confusing, but it seems that in the first six months of Operation Barbarossa some two million Soviet prisoners died of exposure, disease, and starvation in makeshift camps. A further million died in the following three years. Even when prisoners of the Axis powers became valued as a labour source, Russians were at the bottom of the hierarchy. This was a war of annihilation where racial ideology engendered a complete disdain for the enemy.

The descent into savagery, it should be said, was mutual. The Germans who were captured when the Red Army began reclaiming territory from 1943 were terribly vulnerable. Few of the 90,000 men taken at Stalingrad survived: the haunting image in this book of a German POW being guarded by a Soviet soldier speaks to an abject and utter desolation. By one estimate, possibly thirty per cent of German prisoners captured by the Soviets died. This, as it happens, is about the same as the Australian death toll in Japanese captivity.

It is impossible to read this book without despairing about the fragility of international law during long and bitter conflicts. When the Geneva Conventions worked, it was not because of humanitarianism but rather a need for reciprocity and fear of reprisals, such as were triggered when the British shackled German prisoners during the raid on Dieppe in August 1942. But the huge problems of scale and logistics must be acknowledged. In four and half months (1 January to 13 May 1945), the Soviets captured perhaps 2.3 million men. On one day in 1945, the Allied Army Group B in the Ruhr captured 317,000 men. Prisoners in American hands rose from 313,000 to 2.6 million in early April 1945. How do you house, feed, and provide medical care for such masses in the midst of battle? How do you meet the requirements of the Geneva Convention when you are advancing into territory that has been devastated by blockade and bombing, and where the civilian population is starving?

The Allies were unable to solve this problem in 1944–45. Moore contests the more controversial claims that General Dwight Eisenhower deliberately neglected prisoners in order to punish the Germans, but it is clear that chaos prevailed for a time in the Rhine Meadows camps. With massive overcrowding, German prisoners had no shelter other than what they dug in ground; they were exposed to pouring rain without blankets, and hunger and thirst killed many (exactly how many is contested).

Logistics get little coverage in the popular literature of war, but are critically important. The transfer of Axis POWs by Allied authorities to the United States and remote parts of the British Empire – such as Canada, South Africa, and Australia – consumed large amounts of shipping, one of the most critical resources in the British war effort. It was done because Britain feared accommodating large numbers of potentially troublesome prisoners on its own soil.

A review of this length cannot do justice to the many complexities this study reveals. Non-white POWs in German hands, for example, fared worse than their white counterparts, given the racial assumptions of Nazism and fascism, but their conditions were ameliorated when it seemed that political or propaganda gains could be made at the expense of French or British imperial credibility.

Of particular note are the chapters on the repatriation of prisoners after the Allied victory. Many national groups returned home quickly, but Axis prisoners were retained by their captors for some years, to assist in postwar economic recovery. Some Germans became hostages of Cold War politics and were not released until 1956. Soviet prisoners, meanwhile, were stigmatised as traitors by the Stalinist regime, and on their return ‘home’ were interrogated, interned in gulags, or executed. The infamous return of the Cossacks by Allied powers in 1945, Moore confirms, was justified in the minds of Allied authorities by the need to ensure the rapid return of their own prisoners, often held in camps liberated by the Red Army.

This is a dense book, with detail that at times is overwhelming and repetitious, but it needs to be read. Captivity in Europe was rarely a narrative of planning mythologised escapes from, say, Stalag Luft III and the fortress Colditz. Far more commonly, it was a desperate struggle for survival that millions of men and women lost.

Comments powered by CComment