- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Unconscionable carnage

- Article Subtitle: A pioneer of maxillofacial reconstruction

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Two millennia before ‘pretty privilege’ became a TikTok talking point, Publilius Syrus averred, ‘A beautiful face is a mute recommendation.’ The opposite is also true. Facial disfiguration, whether congenital or acquired, can be psychologically and socially debilitating.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

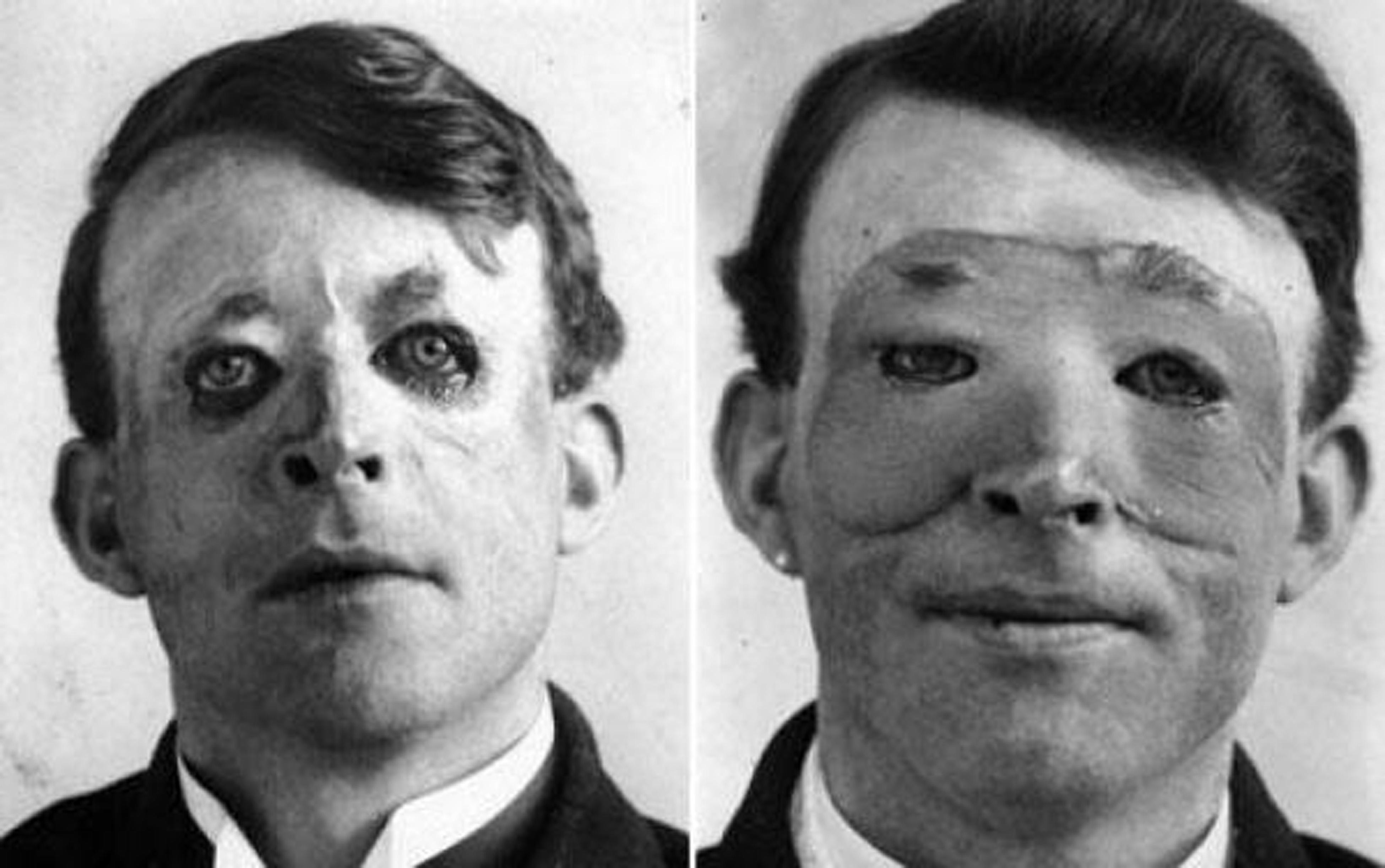

- Article Hero Image Caption: Walter Yeo, one of Harold Gillies’ patients, before and after reconstructive surgery. (Science History Images/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Michael Winkler reviews 'The Facemaker: One surgeon’s battle to mend the disfigured soldiers of World War I' by Lindsey Fitzharris

- Book 1 Title: The Facemaker

- Book 1 Subtitle: One surgeon’s battle to mend the disfigured soldiers of World War I

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen Lane, $45 hb, 336 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/the-facemaker-lindsey-fitzharris/book/9780241389379.html

The surgical work performed by Gillies and his staff to prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet gave primacy to function over form. His first ambition was to save lives, although his rationale does not sit easily with modern sensibilities. He told the Medical Society of London, ‘I would have you know that my first duty is to the Army, and that this involves the sending back to duty of as many soldiers as possible in the shortest time.’

At a time when surgeons were routinely sewing up battle wounds and unintentionally embedding life-threatening bacteria with their sutures, Gillies worked slowly. He reconstructed internal membranes first, then supporting structures such as bone or cartilage, before applying a range of skin-grafting techniques. These interventions typically occurred over numerous operations spaced apart by gruelling recovery periods. The misery of undergoing surgery with primitive anaesthetics such as ether – and sometimes no anaesthetic at all – is marrow-chilling.

Part of Gillies’ genius was an insistence on working with other professionals, most notably dentists, but also radiologists, artists, and photographers. He was given the opportunity, for obvious and appalling reasons, to operate on a vast number of patients and to improve his surgical efforts through trial and error. Early in his career he accidentally transplanted part of a patient’s scalp onto his nose, which in due course sprouted a large tuft of hair. He pioneered a technique called the tubed pedicle, ‘a flap of skin stitched into a protective, infection-resistant cylinder,the free end of which was attached to the site of the injury’.

Fitzharris makes extensive and effective use of letters and diary entries from some of the luckless soldiers who became Gillies’ patients. The book also includes an excellent selection of photographs, graphic depictions of unthinkable injuries, crude surgical responses, and some significant successes.

Unfortunately, the story is ill served by prose littered with foreshadowing and clichés. With grim inevitability we are told that ‘the word “impossible” was not in Gillies’ vocabulary’. There are infelicities: ‘Gillies chose a scalpel as carefully as he might choose a golf club.’ Some sections are redundant. Five pages are devoted to explaining how Gavrilo Princip shot Franz Ferdinand to precipitate the Great War, when a single sentence would have sufficed. Similarly, there is a lengthy recap of the Battle of Jutland, oddly bookended with the thoughts of a cook proofing bread dough on the Vanguard.

More egregious is the spattering of factual errors. The date of the first performance of Aida at the Royal Opera House is wrong by thirty-seven years. Fitzharris calls a golf tournament at St Andrews the English (rather than British) Amateur Championship. It is stated that in 1913, London, a city of more than seven million people, ‘boasted 5 football teams’. She also has Pierre-Joseph Desault coining the term ‘plastic surgery’ three years after he died. These howlers erode confidence in other assertions of fact, and the reader is left pondering how they remained uncorrected through the editing process.

Fitzharris is oddly incurious about anything outside her chosen frame. There is almost no information about what happened to Gillies’ patients in the years following the war, physiologically, psychologically, or socially. She writes extensively of artists including Daryl Lindsay, Francis Derwent Wood, and Henry Tonks, but shows no inclination to consider what impact facial trauma and surgery had on art, particularly the emergence of Surrealism. The book breezes past Gillies’ world-first phalloplasty of trans man Michael Dillon in the late 1940s, and makes no mention of his ground-breaking vaginoplasty for Roberta Cowell in 1951. She is also reluctant to explore the ethics of plastic surgery, simply stating, ‘Harold Gillies never tired of pushing the limits of what surgery could accomplish.’

Ultimately, the greatest impact is delivered by the thirty-six black and white plates. They speak most powerfully about the torment of those devastated men and the imaginative ameliorative work of Gillies. Near the hospital in Sidcup where he worked, certain park benches were painted bright blue and reserved for the sole use of maxillofacial patients. Passers-by knew to avert their gaze. These photos urge us to look, to admit the horror, and observe the inhumanity meted out by some men to their fellow humans.

Comments powered by CComment