- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The great conciliator

- Article Subtitle: The stubborn rise of Anthony Albanese

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

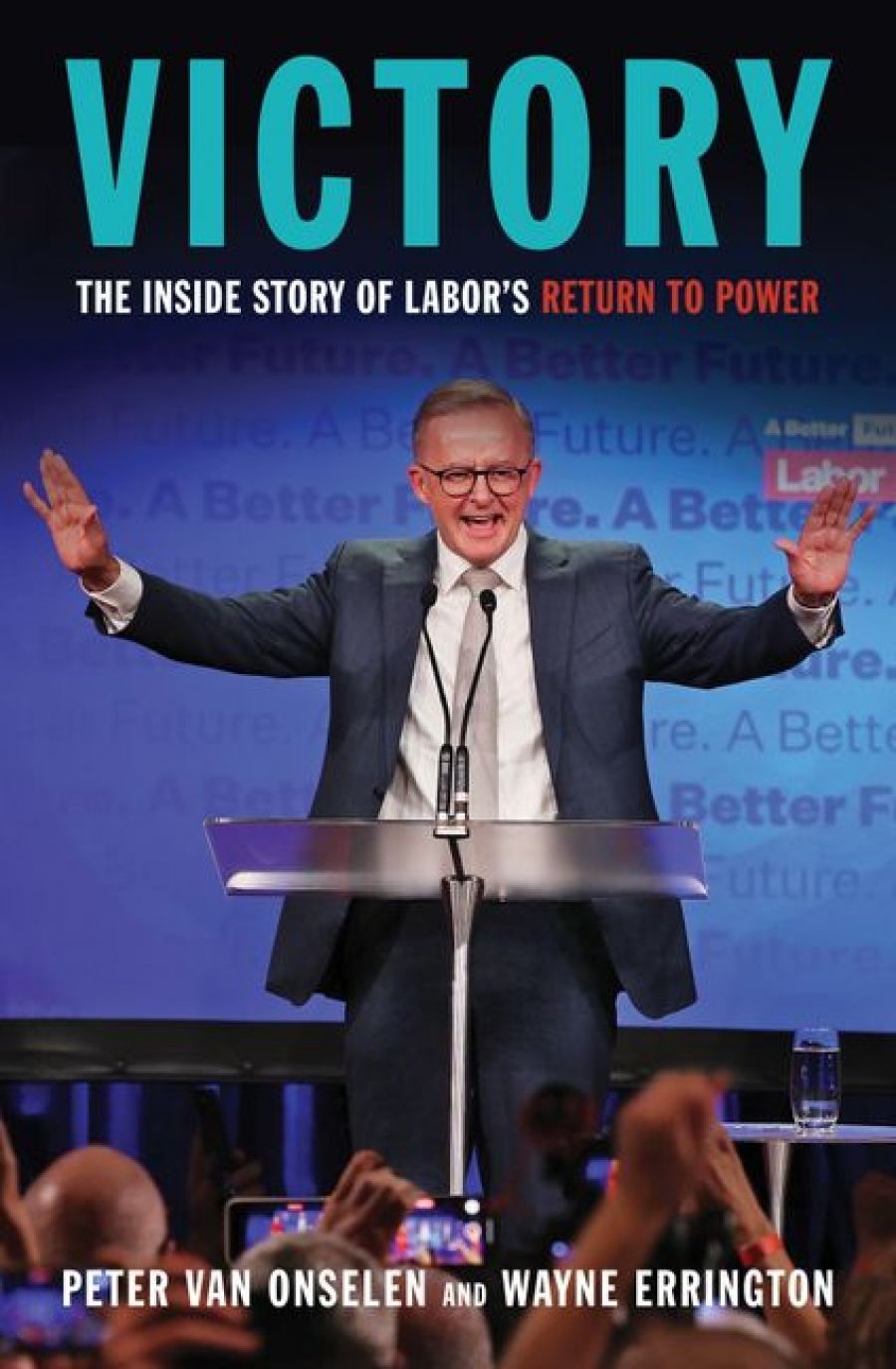

Early in their new book, Victory, Peter van Onselen and Wayne Errington pose a simple question that has haunted Labor since 2019: why couldn’t they beat the other mob? After all, their foe was an ‘incoherent’ and ‘second-rate’ government that had accelerated graft, cynicism, and factional cannibalism, and that had produced, in the end, a long list of tawdry failures. The Coalition seemed entropic.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Martin McKenzie-Murray reviews 'Victory: The inside story of Labor’s return to power' by Peter van Onselen and Wayne Errington

- Book 1 Title: Victory

- Book 1 Subtitle: The inside story of Labor's return to power

- Book 1 Biblio: HarperCollins, $34.99 pb, 320 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/victory-peter-van-onselen/book/9781460763384.html

By early 2022, that wind was a gale and it was blowing hard against the Coalition. Come May, it didn’t so much sweep Labor into government – its primary vote was a historically modest 32.6 per cent – as raze the straw homes of the incumbents.

Unfortunately, Victory is another political book written in great haste to capitalise on recent events. This reflects more the commercial priorities of publishing than the talents of its authors. The book is slightly elevated above the perfunctory by some spitfire analysis, salty denunciations, and the fruits of lengthy interviews with Albanese. (His quotes, woven generously through the book, give the impression of a relaxed and happy victor, holding court with two writers who share his relief and his loathing of Scott Morrison.) But the book covers so much ground – essentially the previous three years between elections – that little is examined in depth. Vast swaths read like journalese written on autopilot. For those interested in politics, Victory may just seem like a breezy recital of recent events they already know.

Victory has its insights, nonetheless. Some of these are minor, such as the revelation that colleagues preferred to email their constructive criticisms to Albanese rather than sharing them with him in person, to better avoid his defensiveness. Some are larger, such as Albanese’s long temperamental transition from the ‘Marrickville Brawler’ to smiling empath.

Albanese’s response to the queen’s death in September – and to the subsequent semi-revival of the republic debate – was a neat demonstration of his approach to power. Albanese was sombre and deferential. He observed the baroque etiquettes of official mourning, which included the suspension of parliament for two weeks, regarded as an obscene and disruptive anachronism by many party members, but it was Albanese’s way of saying to the broader electorate: I won’t meddle with processes arbitrarily or contemptuously. If there are democratic procedures that aren’t working, we will resolve them together – patiently, collectively, and transparently. For now, we observe the rituals of mourning while devoting ourselves to just one constitutional reform in my first term: the Indigenous Voice to parliament.

Vital here was the implication: I am not my predecessor.

The man who for so long was a combatively voluble figure now looms as the Great Conciliator. ‘That mellowing’s taken quite a while,’ Julia Gillard told Albanese’s biographer, Karen Middleton, a few years ago. This mellowing, though, is not merely a function of time, but also derives from the lessons of the first, often shambolic Rudd government (2007–10), in which Albanese served as a minister. He is better at the procedural machinery and relationships of politics, Victory says, than either Kevin Rudd or Morrison. Sure, yes, and let’s hope we’re all the better for it.

Victory ends with some predictions. I won’t share them, because these authors’ previous book (How Good is Scott Morrison, 2021) was predicated on their belief that he was unchallengeably powerful and almost certain to win a fourth consecutive term for the Coalition. As the authors should have known, political fortunes change quickly, and the book’s premise had dated badly before it arrived on the shelves. Earlier this year, van Onselen also predicted that ‘few of the independents challenging moderate Liberals would win’.

Predictions are meat and gravy for the political commentator, but they’re also cheap and ephemeral. It is depressing that so many political books feel like mere extensions, or anthologies, of the daily reporting and commentary that they should distinguish themselves from.

That daily commentary produced one conventional wisdom after 2019: Morrison was a campaigning genius. Electoral triumph, especially an unlikely one, has a way of validating everything that went before it – reporters become naïvely generous in their treatment of cause and effect. The simple truth is that one of two major parties must win, that Bill Shorten was distrusted by many voters, that his platform was ambitiously ‘cluttered’, that Morrison successfully exploited both facts, and that he did so while voters were largely ignorant of how deceitful, bullying, and incompetent he was. But they figured it out.

The Coalition’s federal campaign was jealously governed by Morrison, who retained from 2019 an imperious faith in his own judgement. The result was a historic cratering of his party’s vote, the severe loss of several heartlands, and personal humiliation for the prime minister. And suddenly, the man once heralded as a campaigning savant now attracted this verdict from one of his senior colleagues: ‘The bloke thinks he is a master strategist,’ they told The Saturday Paper. ‘He is a fuckwit.’

Peter van Onselen was one of the gallery’s more conspicuous critics of Morrison – he considered him morally crippled and often cut a lonely figure at The Australian for saying so – but the book has little to say on the stories his peers told about Morrison in his early days of the prime ministership. In addition to the ‘gifted campaigner’, he was also the ‘pragmatist’ – a commonly applied adjective that, with the heavy accumulation of evidence that he was just wretchedly shameless, began to attract hilarious qualifiers like ‘extreme’.

The stories politicians tell about themselves, and the stories that journalists tell about them, can define things for a while – but that doesn’t mean that they’re true, or wholly true. Morrison’s gift for campaigning was ultra-contingent, as most gifts are, and in the end the most important thing we might say about him is that he was very strange and uniquely craven. We can be grateful that his successor will, for the time being at least, earnestly define himself in contrast.

Comments powered by CComment